A Life Worth Living

A new book explores why it’s so hard to resist speculating about the steps we didn’t take.

By Gary Drevitch published August 20, 2020 - last reviewed on September 27, 2020

George Bailey, as portrayed by Jimmy Stewart in Frank Capra’s 1946 classic It’s a Wonderful Life, is one of the most beloved characters in American film. His fans admire all the good he does for his family, his friends, and his entire community. He reflects their principles and their ambitions for themselves. It’s ironic, then, that the movie hinges on the fact that George himself wants nothing more than to escape his hometown, and that when he faces his greatest personal crisis, he finds that he values what he’s done with his life so little that he’s willing to end it.

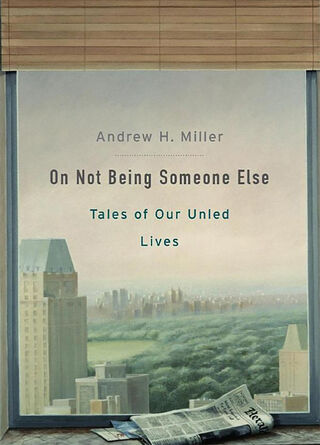

In his sometimes painfully thought-provoking book, On Not Being Someone Else: Tales of Our Unled Lives, Andrew H. Miller, an English professor at Johns Hopkins, considers how poets, psychologists, novelists, philosophers and painters have addressed the uncomfortable truth that humans expend copious mental energy exploring not who they are, but who they are not. He writes that a friend told him the project sounded like “YOLO + FOMO,” and that’s about right. But he challenges readers to go beyond the catchphrases to ponder why they care so much about the people they never became.

Anthropologist Clifford Geertz wrote that we “begin with the natural equipment to live a thousand kinds of lives but end in the end having lived only one,” and literary critic William Empson asserted that “there is more in the child than any man has been able to keep.” Life can be seen as a process of diminishment that, for better or worse, drives the imagination.

Along with It’s a Wonderful Life, Miller considers messages of regret and longing in works by Ian McEwan, Henry James, Jane Austen, Virginia Woolf, Pierre Bonnard, and others, but he recognizes that the question of the unled life is at its core a psychological and philosophical concern. He reviews a body of research dating back to Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky’s 1982 findings on the way we imagine alternate pasts—for example, that our imaginations and self-critical streaks run wild when we just miss a flight but not when we never had a chance to catch it.

There are other rules of regret: Kahneman, Tversky, and those who followed them proposed that finishing second in a competition with three medal winners feels worse than coming in third, because while the bronze medalist narrowly avoided losing out a medal altogether, the silver medalist just missed a victory. Also, we’re more likely to second-guess action than inaction, inappropriate acts rather than appropriate ones, and more recent decisions than earlier ones.

Unfortunately, Miller writes, the real tragedy may not be discovering that a wrong choice set our life on the wrong path, but that, in the end, our choices didn’t make much of a difference. “What if I had…” is a more romantic notion than “Even if I had…,” but it’s not necessarily closer to reality.

Robert Frost’s poem “The Road Not Taken” may be the ultimate expression of Miller’s thesis. In it, as most readers will remember, a traveler in a wood is confronted by two paths, and chooses the road less traveled, which makes “all the difference.” Miller finds Frost’s basic structure—“one person, two roads, retrospection, comparison”—echoed repeatedly in the canon.

To be sorry that you can’t travel two roads at once is to be sorry for being a person. Frost wrote a poem of “metaphysical resignation,” Miller claims, of “sorrow at our inevitable relinquishments.” Speculation about lives unled, Miller posits, may be less about wrangling with our mortality than with our singularity: We can only be one person, and we can only be that person once.

Wistfulness is not a constant presence in our thoughts, fortunately, but there are times it rises up with force—most notably middle age, because it’s when the idea of ever living a different life begins to seem highly unlikely. “When you turn and look back down the years,” novelist Hilary Mantel wrote, “you glimpse the ghosts of other lives you might have led; all houses are haunted.”

We dwell on the choices we didn’t make, and we envy others who seem to have made all the right decisions—primarily, as Aristotle put it, “those who are near us in time, place, age, or reputation.” Curiously, though, and encouragingly, Miller writes, when we imagine being someone else, we may fantasize about having their job, their status, their courage, their partner, or their wealth, but even in those dreams, we remain ourselves at the core, not them. We don’t want to become another person; we want to be ourselves with what someone else has. Beneath the striving, we retain a primitive attachment to ourselves: “It’s not vanity, exactly, but something more elemental and stubborn.”

Miller wonders if his theme is so obvious as to hardly be worth raising, but comes to realize that these yearnings merit analysis, whether through literature or therapy. In the end, he hopes, we may find some comfort in the realization that we are not exceptional in our encounters with our unled lives.

When George Bailey’s guardian angel, Clarence, reviews his charge’s life, he encounters a young man who yearns to see the world, build cities, and achieve acclaim. Circumstance, and his cast-iron character, kept him from those dreams. Clarence’s mission, Miller writes, is to encourage George “to give up thoughts of other lives and to make a home in his own.” This is the message we take away from Capra’s movie and Miller’s book: Of course there were other paths, but we would do well to follow George’s lead and finally welcome ourselves into our own real lives.

Facebook image: fizkes/Shutterstock

LinkedIn image: Boonyarit Nula/Shutterstock