Breaking the Code of the Streets

What can science tell us about how to reduce youth violence?

By Dwyer Gunn published July 5, 2016 - last reviewed on July 6, 2016

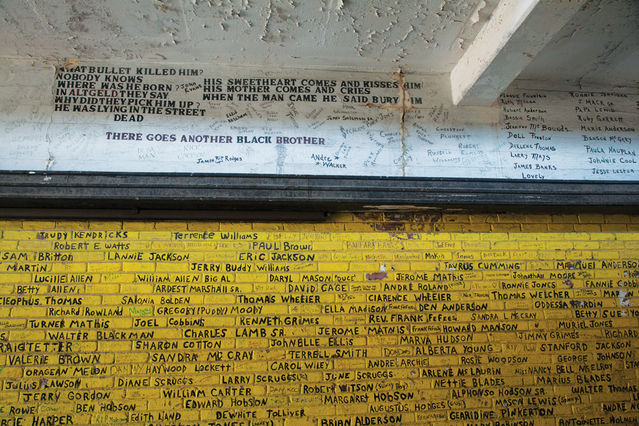

Altgeld Gardens public housing project is on Chicago’s Far South Side, 18 miles from the city’s elegant downtown. It sits between a sewage treatment plant, a freeway, and the sludge-colored Little Calumet River. Built on top of a landfill in 1945, the 190-acre complex of mostly two-story brick apartment buildings originally housed African-American World War II veterans who worked in the nearby steel mills and factories. The industries that once sustained the community are largely gone, although their environmental imprint lingers: In the 1970s, Altgeld was nicknamed the “toxic doughnut” thanks to the waste and pollution that had seeped into its air, ground, and adjacent waterways, and for decades residents have had unusually high rates of cancer, respiratory disease, and prenatal complications.

Tidy carpets of grass and spindly trees border the apartment buildings, some of which were renovated by the Chicago Housing Authority about 10 years ago in an incomplete effort to clean up the crumbling development. The area’s few businesses include a supermarket, a liquor store, and a ramshackle shop called The Connect that sells a small assortment of food, clothing, and prepaid cell phones, and where four people were killed in a 2011 shooting. Located 35 blocks from the end of the nearest commuter train line, it takes an hour and a half by public transit to get downtown, sharply limiting economic opportunities for those who live here. More than half of the project’s residents, nearly all of whom are black, live below the federal poverty line.

The neighborhood struggles with the same high rates of crime and gun violence that plague other parts of Chicago—a long-running epidemic that has seen a sharp uptick recently. This year, there were 1,000 shootings citywide by late April, a grim milestone that wasn’t reached until at least June of the previous four years. As elsewhere in the city, young men are the most vulnerable. In 2014, a 15-year-old boy was shot six times in Altgeld Gardens and died a few days later. Last year, an 18-year-old shot and killed a 20-year-old in the neighborhood. The city’s thousandth shooting victim this year, a 16-year-old boy, was hit in Altgeld.

“It sometimes feels safe here, but then out of nowhere people get shot,” says Wakil Atig, a tall, soft-spoken high school senior with a gentle smile who lives in the project with his mother and younger brother. “It’ll be like six months of quiet, and then three people end up dead. It’s hard because it’s so unpredictable.”

While the situation in Chicago is extreme, it’s not unique: In 2013, the national homicide rate among young men ages 15 to 24 was 18 times higher for blacks than for whites. Social scientists agree that violence among minority youth is the product of a complicated knot of problems. But at the same time as policymakers grapple with macro questions, researchers are looking for stopgap measures that can prevent these young men from ending up dead or in jail. And they’ve hit on an approach that, in targeting automatic thoughts and behaviors, is having an outsize impact.

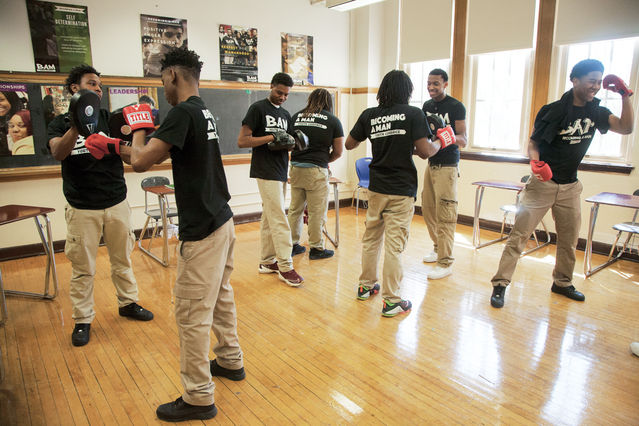

In Chicago, a school-based initiative called Becoming a Man is a rare bright spot on the landscape of violence. Developed in the early 2000s by a local nonprofit called Youth Guidance, the program serves kids in Chicago’s most underprivileged and segregated neighborhoods, including Altgeld Gardens. Students participate in weekly hour-long sessions that combine traditional group therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, mentoring, and academic coaching guided by six “core values”—integrity, accountability, positive expression of anger, self-determination, respect for women, and visionary goal setting.

The program has shown impressive results. The University of Chicago Crime Lab, a research organization devoted to generating rigorous evidence about effective ways to reduce violence, began conducting large-scale randomized controlled trials of Becoming a Man in 2009. The study included thousands of black and Hispanic Chicago boys with an average baseline age of 15, up to a third of whom had previously been arrested. The Crime Lab’s evaluation of the program indicates that it reduced overall arrests by about 30 to 35 percent, reduced violent crime arrests by up to 50 percent, and significantly increased high school graduation rates. It’s also cheap at a cost of less than $2,000 per participant, amounting to a cost-benefit ratio of up to 30 to 1.

Becoming a Man is hardly the only intervention aimed at at-risk boys—dozens of initiatives around the country offer mentorship, tutoring, academic advisement, vocational training, job placement, or some combination thereof with essentially the same goal: to boost their chances of staying out of jail, graduating from high school, and thriving in life. But Sara Heller, a University of Pennsylvania criminologist and Crime Lab affiliate, says that other programs seldom show measurable success.

“If you look at aggregators of evidence, like the U.S. Department of Education’s What Works Clearinghouse, and the programs they’ve reviewed to prevent dropouts and promote school completion, only a couple have shown positive signs,” Heller says. “It’s similar when you look at violence prevention. There have just not been very many success stories for disadvantaged adolescent boys, so people have this sense that nothing works. That’s why it’s remarkable that we see these big declines in crime and increases in school engagement with Becoming a Man. The outcomes are moving—and moving non-trivially.”

A questions remains: Why is Becoming a Man succeeding where many other well-meaning programs founder? What is its secret sauce?

MEN’S WORK

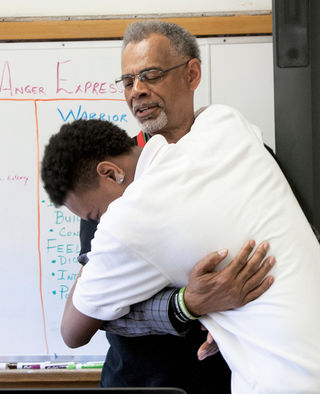

On a frosty morning in January, Wakil Atig and a dozen other students trickled into a classroom at Carver Military Academy, a public high school on the edge of Altgeld Gardens. Dressed in the school uniform of sharply creased blue slacks, a button-up shirt, and meticulously shined black shoes, they took their seats as Jason Montgomery, a Becoming a Man counselor, commanded their attention.

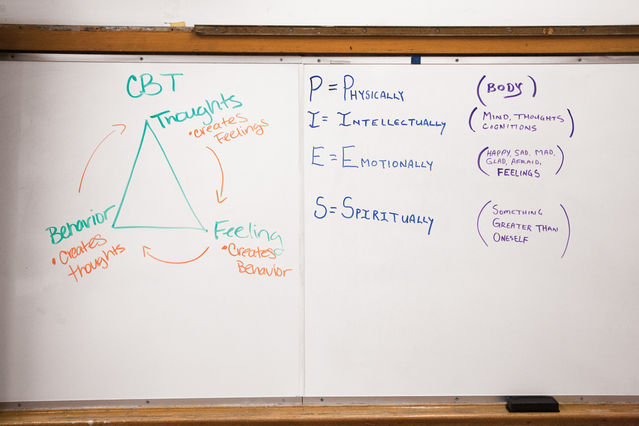

“Let’s start with a good PIES check-in,” Montgomery said, referring by acronym to their physical, intellectual, emotional, and spiritual status. The check-in allows counselors to catch up on students’ lives in and out of school and gauge their current problems. Unlike typical programs in which the therapist maintains personal opacity, Becoming a Man counselors participate in the check-in themselves as a way of modeling openness about their own struggles and victories and cementing trust with the students.

Montgomery, a burly father of two, clad in jeans and a black sweatshirt, went first. He told the kids he was happy to be in the circle but also a little sad. “I have to say I miss my sister,” he said. “She moved away over the holiday.”

The students listened to him intently before offering their own check-ins. One boy shared that he’d been accepted to five colleges over the Christmas break. “I never thought I’d go to college,” he said with disbelief. “I was so proud of myself, I wanted to cry. But I didn’t want to cry in front of my girl.”

“Did you find that space and time to cry?” Montgomery asked.

“Yeah, I did,” the student said.

Another boy told the group that he’d been feeling disconnected at home. “There’s too much anger and commotion, too many drunks,” he said. “I’m not like them. I don’t want to grow up like them. None of them finished high school.”

After the last boy spoke, Montgomery led the group in a breathing exercise. “We had some heavy check-ins,” he said. “Take a moment to feel grounded in this space.”

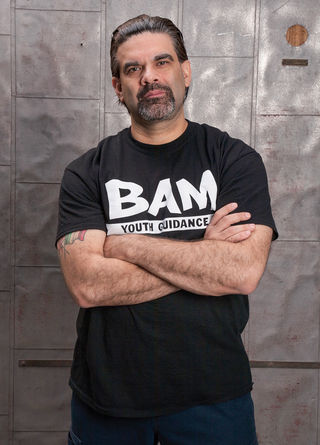

It’s impossible to understand the eclectic combination of methods that make up the program without considering its founder, Tony Ramirez-DiVittorio. A tattooed Italian-Hispanic-American who was born and raised on Chicago’s Southwest Side, Ramirez-DiVittorio witnessed his parents’ divorce when he was 11. It plunged the family into poverty and destroyed his already tenuous connection with his father. Despite his own challenging upbringing, Ramirez-DiVittorio eventually graduated from college, earned a master’s degree in psychology, and was hired in 1999 by Youth Guidance to work as a high school counselor in a mostly Puerto Rican neighborhood of Chicago.

Surrounded by kids who were essentially younger versions of himself, he pioneered the program that would grow into Becoming a Man, drawing on factors that had personally helped him overcome the challenges of being poor and fatherless. Critical to that journey was his martial arts instructor, a tough and caring male mentor who convinced Ramirez-DiVittorio when he was in his early 20s to get his life together and take his studies seriously. “It was the first time in my life I had had fathering,” Ramirez-DiVittorio says. “I had had mothering, but I’d never had a man give me affirmations or tough love or build me up.”

Becoming a Man counselors fulfill that role for their students, alternately challenging the boys to do better in school and in their relationships and supporting them as they navigate turbulent home lives, the bureaucracy of high school, and the pressures of test preparation and college applications. They also provide traditional counseling, incorporating a heavy dose of what they call “men’s work,” which draws on Ramirez-DiVittorio’s own experience in men’s groups inspired by the ancient initiation rites of tribal societies—a process that helped him examine his childhood experiences and construct a healthier sense of masculinity.

“I had to deal with my own trauma,” Ramirez-DiVittorio says. “I had to deal with the 11-year-old who saw violence in his house.”

At Carver Military Academy, Montgomery guided the group in “shadow work,” part of a goal-setting curriculum that helps students identify and overcome unconscious thoughts and behaviors that hold them back. “The shadow is the part of myself that I repress,” Montgomery explained. “It takes some work to find out what your shadow looks like. The toughest thing I had to do as a man was look at the pieces of myself I don’t like.”

Montgomery then staged a demonstration with two students in which one played the shadow and trailed the other, periodically tripping him up as he attempted to go about his day. In a second version of the demonstration, the boy in the lead started acknowledging his shadow, intentionally side-stepping the second boy’s tripping feet. After the exercise, Montgomery led the students through a deconstruction of the lesson, asking them about their own shadow and inviting suggestions about how it could be overcome. “What does it look like? How do we do it?” he asked. “The first step is to acknowledge it. You’ve got to take your shadow and put it in front of you.” The boys nodded.

The lesson was typical of the program’s overarching focus, which is to teach students to slow down and examine their own thought processes. It’s this emphasis that Crime Lab researchers believe is key to the program’s success—because it’s a key driver of youth violence. Prior to studying Becoming a Man, the lab completed an analysis of every youth homicide in Chicago over the course of a year. Most weren’t carefully plotted or even purposeful, but were really automatic, impulsive actions—with dire consequences.

“You hear over and over about gang violence in Chicago, and it’s true that the majority of people who are shot or do the shooting are connected to something one might consider a gang,” says Roseanna Anders, the lab’s executive director. “But when you consider the actual circumstances, it’s often not the case that one guy was selling drugs on another guy’s turf. It’s about girls, shoes, or other stupid things. And unfortunately, in the environment these kids are growing up in, with ready access to guns and the sense that they have to protect their image, these trivial arguments lead to people being shot and killed.”

Everyone acts automatically. We wake up in the morning, stumble to the shower, brew our morning coffee, and commute to work, all without devoting much mental energy to the myriad decisions we’re making along the way. “Automatic behavior is adaptive,” says Heller. “It’s generally a good thing because we can’t actually consciously think of everything that we need to respond to.”

While many automatic behaviors are benign, those developed by kids growing up in neighborhoods like Altgeld Gardens are more problematic—they are adapted to an environment in which establishing and maintaining a certain kind of reputation is seen as crucial for survival.

Lawrence Williams, an assistant professor of marketing at the University of Colorado Boulder who studies judgment and decision making and who is not part of the Crime Lab, says that “to the extent that the cues present in disadvantaged neighborhoods systematically differ from those in middle-class places, you’ll find systematic differences in behavioral responses.”

To illustrate the point, Anuj Shah, a University of Chicago psychologist and Crime Lab researcher suggests, imagine being a teenager in a movie theater goofing around with friends when someone bigger and tougher tells you to sit down and be quiet. Then imagine that you’re hanging out with your friends in a classroom and the teacher tells you to sit down and be quiet. “If you grew up in a safe neighborhood, then you probably treat both situations the same way—you just sit down and be quiet,” says Shah. “Importantly, though, you do it without thinking. You do it automatically.”

But in a tough neighborhood, kids quickly learn that if they back down every time someone on the street confronts them, they’ll be attacked over and over again. “They have a lot of situations in which the adaptive, automatic response is to be aggressive and stand up for themselves,” Heller says. “Sometimes that actually is good for them because the reality of the street, unfortunately, is that you if you don’t do that, you can get continually victimized.”

The downside, however, is that kids with an automatic impulse to counter aggression can lose the ability to slow down and distinguish between situations when that reaction is protective and when it can have negative, even devastating, repercussions. In the classroom, resisting when a teacher tells you to sit down and be quiet can get you suspended or expelled. On the street, mouthing back to someone who lobs an insult can get you killed. Shah thinks that the success of Becoming a Man comes from teaching techniques that allow the boys to reflect on the optimal response to each situation—leading to better grades and graduation rates, as well as to less violence.

“If someone bumps into him on the street,” Shah says, “now the kid can say to himself, ‘Am I ever going to see this person again? Is it possible this person is carrying a weapon?’ The code of the street is different from that of the classroom, and there are so many different codes for different situations. Unpacking those situations and thinking about how they’re different helps him decide: ‘Is this a time when I need to fight back, or do I not?’”

THINKING SLOWLY

Becoming a Man doesn’t promote blind compliance. There’s nothing in the curriculum that instructs students to obey a teacher, do homework instead of play video games, or stand down when confronted on the street. In fact, one of the first things counselors affirm for students is that sometimes they might indeed need to fight. Part of what makes the program so interesting to researchers is specifically that it doesn’t distinguish any behaviors as good or bad. It simply teaches the boys how to be more deliberate in their thinking.

Laboratory documentation provides the strongest proof that a cognitive shift is in fact occurring. As part of their evaluation, the Crime Lab researchers observed Becoming a Man participants playing an “iterated dictator game,” a game in experimental economics that assesses thought processes behind everything from fairness and altruism to punishment and retaliation. Students were timed while deciding to what degree they should retaliate against unfair behavior by someone they thought was another kid at their school, and the researchers found that those in the program spent nearly 80 percent more time thinking before deciding than did those who hadn’t been in the program.

The results suggest that reductions in youth violence aren’t contingent on changes in emotional intelligence, self-control, or much vaunted “grit,” but rather on automatic thinking. It’s a hypothesis, Heller clarifies, although “it’s a hypothesis that comes out of the data and out of a lot of thinking and reading about adolescent decision making.”

Crime Lab researchers aren’t able to say for certain which element of the wide-ranging program produces these outcomes. “This intervention is a package of things,” Heller says. “It might be that the mentoring and the thinking about emotional processes are how you get less automaticity, but without experimentally varying each element, you can’t be sure.” And although Crime Lab researchers have established that Becoming a Man seems to help kids avoid impulsive mistakes in the short term, they don’t know its exact long-term effects. The program may help kids envision a future for themselves and take steps to get there, but it remains to be seen whether it yields the higher college graduation rates and lower rates of nonmarital childbearing that are generally needed to break the cycle of intergenerational poverty.

Yet even the established benefits of Becoming a Man might have outsize effects given the age group of its participants, Heller points out. Just keeping adolescent boys out of trouble for a few critical years can change their lives. “We call it the age-crime curve,” she says. “Crime starts in the early teens, often peaks in the late teens, and then tends to fall off very quickly in the early 20s. Obviously there are adults committing crimes, but when we think about the kind of street crime that cities are most worried about, it’s almost all young offenders. A program effect doesn’t have to last forever to make a lifelong difference.” Even if all Becoming a Man does is help a kid avoid a weapons charge or a stint in juvenile detention, that could mean deflecting the grievous effects that can snowball from having a criminal record or spending a month surrounded by other young offenders. Perhaps most important, Heller says of the Crime Lab’s findings, is the confirmation that “adolescence is not too late. There is actually something we can do, even without changing the root causes of crime, that can make a big difference.”

People in high places are paying attention. In 2013, Mayor Rahm Emanuel allocated $2 million to Becoming a Man, which enabled the program to more than triple the number of participants it serves from 600 to 2,000. In 2014, President Barack Obama unveiled My Brother’s Keeper. A national initiative to provide opportunities for young men of color, it has prominently featured Becoming a Man and has allocated $6 million in federal funding to support its expansion and ongoing evaluation in Chicago, along with a companion tutoring measure. The program now serves 2,500 boys at 48 schools.

For some former participants, the lessons in impulse control and positive expressions of anger still resonate. Wero Villagomez, a 2012 high school graduate who participated in Becoming a Man in his freshman year, says that before reacting in tense situations, he still pauses to consider the training he received in the program. “It just makes more sense than reacting badly,” he says, noting his determination to pass the lessons on to his 6-year-old nephew and 1-year-old son.

Wakil Atig graduated from high school last spring with nearly all As, and he’s college-bound this fall, intending to study journalism. He credits Becoming a Man with helping him devise and execute the plan that led to his college acceptance, and also with instilling in him a different vision of his future.

He would like to mentor young men and, eventually, to have a family and be the kind of father who’s around day in and day out. “I’ve never woken up in the house with both my mom and my dad,” he says. “I want my kids to have that.”

When he reflects on the cognitive and behavioral adjustments that have taken him this far, he recalls one moment last year when he went to look for a book in his locker. A school security guard approached to ask what he was doing there—a new school policy forbade students from being in the hall during class without a hall pass. A few years earlier, Atig says, he might have impulsively given the security guard a show of attitude even though he was holding the hall pass in his hand. Instead, Atig took a careful breath and asked himself a question: “What’s the benefit of reacting like that?” He handed over his hall pass, got his book, and went back to class.

Submit your response to this story to letters@psychologytoday.com. If you would like us to consider your letter for publication, please include your name, city, and state. Letters may be edited for length and clarity. For more stories like this one, subscribe to Psychology Today, where this piece originally appeared.