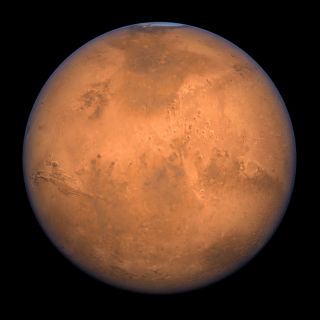

Meet The Martians

The 100 finalists for Mars One's proposed one-way mission to begin colonization of the red planet say they're ready to leave earth forever. What's propelling them into space?

By Faye Flam published July 8, 2015 - last reviewed on June 10, 2016

George Hatcher wants to let a private outfit rocket him to Mars—and leave him there. Hatcher, a 35-year-old aerospace engineer who repairs, tests, and launches rockets at the Kennedy Space Center and is pursuing a Ph.D. in planetary science, tried twice to get into NASA’s astronaut program. But he wasn’t selected.

Now he’s taking his chances with Mars One, a nonprofit group based in the Netherlands that’s proposing to seed a permanent, independent human colony on Mars, starting with four volunteers and adding four more every two years. The colonists would grow their own food, generate their own energy, and use deposits of Martian water to produce oxygen. But there would be no return flights—all colonists would die on Mars.

In March, Hatcher was named one of the program’s 100 finalists. He says he fully understands that Mars One would be very different from a NASA mission. The federal agency has to plan within the bounds of what the public deems reasonable risk, which precludes such bold ideas as stranding people on a distant planet.

A voyage to Mars takes about seven months, and flying one-way has practical merits, Hatcher says. Since 90 percent of a rocket’s weight comes from its fuel, a mission becomes much simpler and cheaper if it can skip the return trip. But the average surface temperature on Mars is –81 degrees Fahrenheit. Without an external source of oxygen, humans can’t breathe, and the lack of atmospheric pressure would cause deadly bubbles to form in the blood. A study by a group of MIT students concluded that Mars One, as currently proposed, lacks a workable plan to grow sufficient food or maintain breathable air, without which the volunteers would likely die after just a couple of months.

Mars One officials say they won’t launch anyone until they test a working pressurized habitat on the ground. Still, space-travel experts have scoffed at the proposed launch date of 2027, and some flatly call the mission a scam, in part due to the application fee for candidates, though it ranges from just $2 to $38, depending on one’s country of origin. Mars One would need to raise billions of dollars. According to its website, founder Bas Lansdorp, a Dutch energy entrepreneur, says he plans to cover some expenses by turning the selection process, and eventual mission, into a reality TV show.

Mars One has already taught us one thing—there’s no shortage of highly educated people willing to die on another planet. Whether or not the mission ever gets off the ground, the personalities of its volunteers raise some probing questions: What drives people to sign up for such a risky venture? Could crew members maintain their sanity after being together so long in their ship and, if all goes well, their distant, spartan habitat?

In an age of instant communication, a voyage to Mars shouldn’t doom volunteers to the loneliness associated with earlier isolated, high-risk expeditions like those to the North and South Poles. Depending on the relative positions of the two planets, there would be an electronic communications delay of up to 20 minutes between Earth and Mars. That would make ordinary conversation difficult but not social networking. With fame and a close-knit group of colleagues, our first Martians might find themselves more connected than they were on Earth—that is, if they don’t drive one another crazy.

The Right Stuff?

To assemble not just a competent but a compatible crew, Mars One hired Norbert Kraft, who trained as a cardiologist and has studied the physical and psychological challenges of long-duration space flight for both NASA and the Japanese space agency.

More than 200,000 people responded to the program’s initial call for video applications—“Some were naked,” he says. Mars One had imposed an application fee in part to limit the number of videos from inappropriate candidates. Still, only 1,058 of those initial applicants appeared reasonably serious, he says. After reviewing medical histories and performing a preliminary screening, Kraft helped whittle that group to 660.

For the next cut, he assigned applicants some practical material to learn—including facts about the hazards of long-duration space flight (radiation exposure, bone loss, and muscle wasting)—and then quizzed them on the information. The task had a dual purpose: Getting the right answers showed that the candidates were good learners, but also that they understood what they had signed up for.

The Mars One pioneers will need to be versatile and efficient: The crew would be sent to Mars with a small life-support unit they would need to build into a permanent habitat. They will all have to be able to function as doctors, farmers, electrical engineers, and chefs, Kraft says.

Tristan3D / Shutterstock.com

Kraft asked applicants what they’d do if they had a chance to return to Earth after three years on Mars—then disqualified many who said they’d come home. He wants only volunteers who would put the needs of the team first and fully commit to the goal, he says. That left him with 100 people, which he will later reduce to 24.

Given the quality of the candidate pool, Kraft says, he could select a full crew of Ph.D.’s, but he’s more interested in the way people show him they would function on a team. “If the group has one bad apple it becomes a disaster,” he says. “Things go down the drain.” On Mars, something like leaving a sock on the floor or failing to roll up the toothpaste tube could lead someone to explode—and that’s no hyperbole.

Close-Quarters Combat

In selecting its team, Mars One can take advantage of NASA research on how humans respond to lengthy space flights. A two-way manned mission to Mars has been a long-range goal of the space program for decades. To that end, it has used the International Space Station and various ground-based simulations to study which kinds of people are more likely to get depressed, impulsive, or even violent in isolation and close quarters.

Kraft witnessed one such experiment from the inside. In 1999, he lived for 110 days in a tunnel with two Russian men, a Japanese man, and a Canadian woman. Trouble ensued.

First, one of the Russians misread the friendly behavior of the Canadian woman. “He thought she was in love with him,” Kraft says, and so, one day, he tried to kiss her, without asking, and she accused him of sexual harassment.

Then the Russians got into a fistfight. One of them aspired to be a cosmonaut but had poor English skills and no Ph.D. The other had both and taunted his compatriot over their disparity. The ensuing brawl, Kraft says, was terrifying. Afterward, the Japanese crewman ran out of the tunnel and abandoned the test.

The longest mock Mars mission to date, called Mars 500, kept six men isolated in a faux spaceship for 520 days. University of Pennsylvania psychiatry professor David Dinges used onboard cameras, wristbands, and other systems to monitor the volunteers from his lab. The results were eye-opening, and sobering: One man developed severe insomnia; another fell into an abnormal sleep cycle that kept him out of phase with his crewmates. Both experienced a decline in cognitive skills. Meanwhile, another participant became depressed, and still another developed impulsive behavior that persisted throughout the mission. One of the six did survive quite well.

Dinges declines to comment directly on Mars One’s prospects, except to say that he favors missions that would bring astronauts back home. “NASA is pushing very hard for this goal,” he says, “but they want to do it in a rational way.”

The experts agree that social factors would be crucial to any Mars mission, one-way or round-trip. Among other concerns, people in long-term isolation have been found to pick a scapegoat, says Nick Kanas, a University of California psychiatrist who has studied the stresses of space flight for NASA. Any discomfort—be it temperature, food, or boredom—often gets blamed on that one person.

Kanas calls Mars One’s plans “not completely outrageous” but would prefer a more modulated approach—perhaps first establishing a moon base from which round-trip Mars voyages could launch and return. “The problem with this mission is they are going to jump really quickly into areas that are unique to the distance of Mars,” he says. For example, “nobody has ever experienced the Earth as an insignificant dot.”

Despite the unknowns, Mars One candidates see the program as the only door open to them in pursuit of their lifelong dreams. Some said in their video statement that being an astronaut is an ambition they’re willing to die for.

Emergency room physician and Mars One finalist Leila Zucker, 46, of Washington, D.C., says she understands she would die on Mars, but to her, that’s a form of immortality. “Who was the first person to walk on the moon?” she asks, rhetorically, assuming that being among the first humans to step foot on Mars would enshrine her name in history alongside Neil Armstrong’s.

Still, Zucker knows she’d be immortal only as long as there are humans to remember her, which goes to another core element of many candidates’ Martian dreams—the conviction that colonizing Mars is vital for preserving the race, which they see as just one pandemic or nuclear war from extinction. “If humans don’t expand to other planets, we will stagnate,” she says. “We can’t stay on this planet forever—I would argue, Let’s go now.”

Hatcher pursues a different kind of immortality. “If I didn’t believe in life after death, I don’t know if I would have applied,” he says. As a young adult, he converted to the Baha’i faith, whose adherents believe in an infinite, dynamic afterlife. Also, for him, Mars One is not just about preserving humanity but inspiring it by unifying people in support of one spectacular mission. “It demonstrates what we are capable of when we cooperate.”

Mars One officials have compared their mission to the voyages of Columbus, but there’s a crucial difference. Columbus thought he was sailing a new route to India—a land where he knew he’d find people, food, and breathable air—and he had some confidence he’d return home.

Kraft realizes that a one-way flight to a barren planet is not something most people would sign on for, but he thinks his finalists are sane. “Humans always strive to learn new things—to learn what’s out there in the universe,” he says. “Some people love to do new things and others want to have an 8-to-5 job and live in the same house.” To him, the candidates represent just an extreme end of the risk-tolerance spectrum.

But would he go? Sure, he says. Martian gravity is about a third of Earth’s, which could have dangerous long-term effects on young bodies but might be rather pleasant for senior citizens with arthritic knees or bad backs. Kraft says he’d like to retire there.