The New Cancer Survivors

Extraordinary advances have turned cancer from an apparent death sentence into a manageable chronic illness for many. But what does it mean to live with a terminal disease...interminably?

By Wendy Paris published March 9, 2015 - last reviewed on April 26, 2017

Brad Slocum wasn’t too concerned when, at 46, he started noticing blood tainting his urine. He knew this was a common occurrence among athletes and other vigorous exercisers, and he had always been one of them. In high school and college he was a competitive wrestler. Later, as an adult living near the ocean in Southern California, he surfed or played beach volleyball regularly. In the winter, he and his wife went skiing at Mammoth Lakes in the Eastern Sierras. He seemed to be in great shape, and his annual checkups confirmed it.

But over the next few months, the faint pink deepened to crimson red. He also experienced inexplicable fatigue and back pain. In September 2005, he went to see his doctor. Preliminary tests showed a large mass growing in and around one of his kidneys. Further scans revealed that he had stage 4 metastatic kidney cancer. His doctor told him he might have six to nine months to live.

Slocum was a new father at the time—he and his wife had a 10-month-old son. Adding to his personal bounty, he had recently sold an institutional money management firm he had cofounded to a large financial services conglomerate, bringing him affluence and an unprecedented sense of professional achievement. Hearing his doctor deliver the terminal diagnosis was like being slammed in the head with a lead brick. In one dizzying instant, Slocum went from believing that his life couldn’t be better to learning that it would soon be over.

“I’m kind of sarcastic, particularly in periods of distress,” he said recently. “My initial reaction was, ‘OK, what’s the good news?’ My doctor said, ‘There is no silver lining here. I have no good news.’ He was very blunt and serious, which didn’t make it any easier.”

Slocum couldn’t sleep for two days. He embarked on the “horrific” process of revealing his prognosis to the most important people in his life—his wife, mother, siblings, business partner, and close friends. The whole thing felt vertiginous and surreal. Six to nine months to live? It was the kind of grave pronouncement he thought was spoken only on television, or to other people, but not to him. Although he had never been much of a drinker, he bought an oversize bottle of bourbon and guzzled it in a week to numb his distress.

He had surgery to remove the kidney mass, but a subsequent CT scan revealed additional tumors on his lungs. By then, Slocum’s shock had begun to subside, and he was snapping back to his usual health-conscious, take-charge, beat-the-competition self. He eliminated red meat from his diet and limited sugar, dairy, alcohol, and caffeine on the advice of an oncologist who specializes in integrative medicine and nutrition and who told him such foods might contribute to the growth of cancer cells. He dove into researching the most promising drugs and clinical trials for his condition. As the six-month mark approached, he was doing OK. Then came the nine-month mark. Not only was he still alive but a scan showed that his lung tumors were no longer growing.

The months turned into years. Against the odds, Slocum’s terminal cancer became something that he lived with and managed. In some ways, it became like a game of high stakes Whac-A-Mole—more metastases popped up in his lungs, pancreas, and shoulder blade, and he attacked them with surgery, chemotherapy, and cutting-edge drugs like Sutent, a targeted therapy for advanced kidney cancer. Meanwhile, he kept on working, exercising, surfing, skiing, traveling, and raising a family—he and his wife had two more children after his diagnosis. Cancer seemed only to intensify Slocum’s innate strengths and personality traits as someone who was naturally optimistic, deeply spiritual, and passionately driven.

Now, nearly a decade after his diagnosis, he harbors no illusions about the tenuousness of his existence. “It’s an ongoing heavy sentence that hangs over me like the Sword of Damocles,” he says. “The hand I was dealt was very grim, yet it’s nine and a half years later and I’m still here, living a reasonably normal life. It’s a strange place to be. In many ways, I feel as if I’m flying without a net.”

Slocum is hardly alone. Advanced cancer used to invariably imply a swift and steep decline. Especially before the advent of radiation therapy and chemotherapy in the early- and mid-20th century, respectively, it was a veritable death sentence which explains the powerful stigma that surrounded it. But while receiving any type of cancer diagnosis is still terrifying, a multitude of developments in recent years have radically altered the outlook for many of those afflicted, and in the process fundamentally changed what it means and feels like to have the disease.

“I’ve seen it turn from a deadly illness into something that people can live with,” says Julia Rowland, director of the Office of Cancer Survivorship at the National Cancer Institute and a pioneer of psycho-oncology—an interdisciplinary field that addresses the psychological and social dimensions of having cancer. “This is one of the big questions now: Is cancer going to become simply a chronic illness?”

Increasingly, the answer seems to be yes. And as more and more people are living with cancer as a chronic manageable condition, often outlasting the crushing prognosis that the disease will cut their life short, the psychological nature of their situation becomes clearer. Theirs is a hyper-real, intensified state of existence in the liminal space between being terminal and cured. In many cases, after believing that their death was imminent and coming to terms with that fact in whatever way they could, they find themselves instead navigating a new and wildly uncharted reality. Their lives, unnervingly interrupted, are resumed in a form that is somewhat familiar but permanently altered.

“What’s remarkable is that most people manage to get on with life, even with very complicated regimens and treatments,” Rowland says. “The difficulty is that it’s not like diabetes. The pathways are not as well delineated. They are living beyond limits. They’re living with the unknown all the time.”

Paths To Longevity

Several broad forces have contributed to the transformation of cancer over the past two decades. The first is early detection. The preponderance of screening tests along with new, more refined imaging technologies have led to the discovery of tumors earlier than ever, often before they’ve spread beyond the original site. And even in the case of metastasized tumors, catching them early can improve a person’s ability to weather treatment and fight the disease.

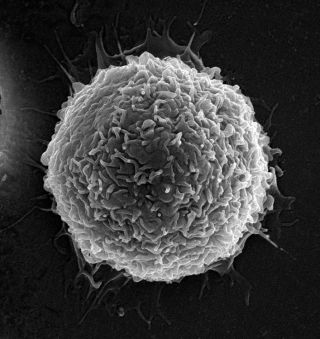

There have also been remarkable medical advances, including targeted therapies, which are drugs designed to act against particular molecules involved in cancer-cell growth in specific types of cancer; personalized medicine, which allows doctors to identify and respond to genetic and biological abnormalities in an individual patient’s cancer; and targeted immunotherapy, a new type of treatment that harnesses the body’s own immune system to destroy cancer cells.

Last is the growing field of psycho-oncology, which has led to an expanded understanding of cancer patients’ emotional and social needs and has been shown to add not just to the quality of their years but to the quantity as well. Being better informed and supported can motivate people to work on their overall physical wellness and opt to participate in experimental treatments and clinical trials, which can be life-extending.

All these developments are factors in the increasing number of people whose cancer can be considered cured, a nebulous term that generally describes those who are cancer-free five years after their diagnosis. But at the same time, they’re enabling more and more people like Brad Slocum to live longer with active or persistent cancer, including tumors that are controlled without being eliminated or tumors that go through continuous cycles of remission and recurrence.

“It’s very different from being cured,” says Michael Fisch, chair of general oncology at the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. “Being cured becomes a story like, ‘Back in 2002, I had a small breast tumor, and they took care of it,’ or ‘I had a small melanoma removed five years ago, and I live a normal life now.’ It’s a line item on a medical history that maybe isn’t too important. But taking Sutent, or periodically having surgeries, or having a lot of CT scans, or having a fear of recurrence or progression, or being on maintenance chemotherapy—that’s a different experience.”

For Joe Blumberg, part of the experience has been enduring cancer’s invasion of his thoughts in addition to its presence in his body. Blumberg’s prostate cancer was discovered in 2006 when he was 65—a common scenario for men his age and typically one with an excellent prognosis. Although the tumor was removed, two years later it was found to have spread—a metastasis with a far more grim five-year survival rate of 30 percent. He tried everything, including chemotherapy, several different drug regimens, and a promising course of immunotherapy. As a stage 4 cancer patient, he recently passed the five-year mark and now monitors and manages his disease with available treatments while hoping for the emergence of new ones. He finds that the disease is never far from his mind.

“Once you’ve been diagnosed with cancer, you’re constantly on guard,” Blumberg says. “You don’t know if you’ll be cured or if it will return. I try to live my life so that I don’t think about it all the time. When I’m swinging a golf club, I’m not thinking about cancer. But it’s hard. I probably think about it half the time.”

How Life Goes On

Susan Gubar, a literary critic and English professor emerita at Indiana University, was diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 2008. She was 63 and given a prognosis of three to five years to live. It shook her to the core. “I felt as if I were a bird flying in the beautiful blue yonder, and I was shot out of the sky,” she says.

Gubar had a radical and debilitating “debulking” surgery in which doctors removed her tumor and abdominal organs, followed by 20 weeks of chemotherapy and surgery for treatment-related infections, as she recounts in her book Memoir of a Debulked Woman. After a year of remission, she found herself facing recurrent ovarian cancer and, once again, chemotherapy. Her cancer came back over and over, with the length of her remission periods shrinking after each bout of chemo. She began thinking that it might not be worth putting herself and her family through the dreadfulness of chemotherapy for ever-diminishing periods of wellness.

Then her doctor enrolled her in a targeted-therapy clinical trial in 2012. Since she started the new regimen, her cancer has been kept in abeyance, and she passed her five-year survival prognosis in 2013 while on the drug. Medically, she says, “the last two years have been absolutely wonderful. No infections—just these pills. It’s been miraculous.”

Gubar now takes four pills every morning to keep her tumors at bay and has monthly blood tests as well as regular CT scans. The limbo state for her involves physical side effects, including hair loss and fatigue, as well as deeply complex psychological effects. “I’m much more aware of my mortality on a minute-by-minute basis than I ever was in my life,” she says. “There are many days where I feel that my foreshortened future absolutely expands my present. There’s a sense of the preciousness of the moment—gravy days, days that are just wonderful. But there are other days where I feel a great trepidation. It’s not like chronic asthma or chronic diabetes. The term chronic is not commensurate. With cancer, there’s always this extraordinary dread of recurrence, of tumor growth, and incredible fear and uncertainty about what the future holds.”

This range of emotions—the simultaneous gratitude and dread, the intense awareness of both the exquisiteness and capriciousness of life—may of course be felt by anyone with cancer, from those with the most promising prognosis to those with the least. But for people whose cancer can be explained only as a chronic condition, the inner stew is often far more pronounced because of the sheer length of time they have to deal with it and the utter uncertainty about how it will unfold.

Socially, relationships can be harrowingly strained as couples and families cope with the pressures of caregiving and the fear of losing a loved one—a fear that’s emotionally corrosive in any case and even more so when prolonged. Medically, one downside of chronic cancer is that patients are facing the late effects of primary treatments that they previously may not have lived long enough to experience, like lymphedema years after lymph nodes are surgically removed or heart problems due to chemotherapy.

Another common challenge is so-called “financial toxicity,” a term that oncologists recently coined to describe the draining of patients’ coffers as they deal with costly out-of-pocket expenses—an issue for many cancer patients, but particularly those whose treatment may persist indefinitely. A 2011 paper in Current Oncology Reports referred to financial pressure as chronic cancer’s unspoken “giant in the room” and projected an increasingly common scenario of patients who are being kept alive with targeted drugs or immunotherapy that may cost upwards of $100,000 per year. They may be “faced with the profoundly painful ‘choice’ of discontinuing treatment and letting ‘nature run its course,’ or the family can sell their home or possibly forfeit their children’s education or inheritance to permit the therapy to be continued.”

Perhaps the most common consequences are anxiety and depression, which themselves can become chronic when cancer never goes away. “Lack of control and predictability is highly stressful for any human being,” says Matthew Loscalzo, the executive director of supportive-care medicine at City of Hope, a cancer research center in southern California. He estimates that people coping with chronic cancer now comprise about 20 percent of his patients. “People who get three or six months or even a year’s worth of treatment and then are considered cured have to cope with the experience of an acute illness, but once the treatment ends, they go back to a new normal and get on with their lives. For those with chronic illness, it’s much, much harder. They are much more likely to have chronic anxiety and depression because they get so exhausted by the treatment, the difficulty of maintaining work, the difficulty in their relationships, and living with uncertainty.”

Yet as researchers are learning more about the character of people who are “managing their disease for years or even sometimes decades,” says Keith Bellizzi, an associate professor of psychology at the University of Connecticut and himself a cancer survivor, “we’re realizing that not only do they deal with the negative aspects of their disease and treatment-related side effects, but there are also positive aspects. Having all of these reactions is completely normal. The positive and negative aspects coexist.”

While no one would wish to have cancer, enduring a precarious disease of cyclical intensity can brush a shimmering topcoat over otherwise ordinary days, generating an intense appreciation for the here and now. It can make moments of interpersonal connection feel deeper, bird calls sound more magical, the brisket taste just as sublime as something out of Proust. Rowland recalls how early in her career, in the 1980s, patients were surveyed just about the damage that cancer wrecked on their lives. “It was only in the write-in sections of the questionnaires that people would say things like, ‘It’s put my entire life in perspective for me,’ or ‘I found out who my five really good friends are,’” she says. “We never asked about that. But now we know that most people will tell you about some positives of their cancer experience.”

A certain subset of people don’t just identify some positive aspects of cancer, but undergo profound changes—a sign of what’s known as post-traumatic growth. “There’s resiliency, which most people have,” says Loscalzo. “Then there are those who just thrive. They deepen their relationships, they change jobs, they change their philosophy about life. Cancer changes their lives for the better.”

For Lucy O’Donnell, it prompted a swift reorientation of her focus and dramatically magnified her sense of being in the moment. In 2011, O’Donnell, then a 46-year-old mother of three and successful health food entrepreneur, had a mammogram that revealed a tumor; it turned out to be stage 4 breast cancer. Further tests showed that it had spread to her liver and bones. She had a 20 percent chance of surviving more than five years. “From the moment I was diagnosed, I didn’t have time to be angry,” she says. “I sat down and thought, Right. This is so serious. I have to accept what I have and do everything I can to get well. I’ve always been quite a clear person, but I never had the confidence that I have now to make decisions.”

O’Donnell immediately shut down her company and began chemotherapy, followed by a radical mastectomy, radiation, and radiofrequency ablation for the lesions on her liver—a total of nine surgeries. Last year, she entered a targeted immunotherapy clinical trial. O’Donnell hopes this treatment will push her into the group of those managing and living with their disease far beyond their prognoses. In the meantime, she’s focused on relishing every second she has. “You just realize what is important in your life and appreciate all that goodness,” says O’Donnell, who wrote a book of advice based on her situation, Cancer Is My Teacher. “Getting this illness completely changed my whole outlook. I don’t take anything for granted: The dew on a blade of grass is a magical thing, as is just hanging out with my children. Every day is a great day, really.”

In their ability to live fully in the present, people in cancer’s limbo may actually have something important to teach those of us who live more or less in denial of mortality, always oriented toward our imagined future. This was one of Bellizzi’s enduring lessons from his encounter with cancer.

“We’re all terminal,” Bellizzi says. “We’re all dying with each passing day, and there’s no way to get around that. I have found that starting my day with that thought helps me change my priorities and perspective. I try to never forget to tell people I love that I love them. If I get in a fight with a family member, I make sure to fix that before I go to bed. We don’t know what’s around the corner. I think it helps us live that way by reminding ourselves that it’s not cancer but life that’s a terminal condition.”

Making It Better

Myriad factors affect how life with cancer is handled, including one’s natural tendency toward optimism or pessimism, physical health, financial resources, and level of social support. As people increasingly face the disease as a chronic condition, experts are pointing to actions and cognitive feats they can undertake to fortify themselves.

Professional mental health services can be invaluable for combating anxiety and depression; methods that help reinforce a sense of meaning and life purpose have proven to be particularly beneficial. At Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, cancer patients and caregivers can participate in a meaning-centered psychotherapy program that helps them see that they have control over their attitude in the face of suffering. They learn that meaning can be derived from creative expression, receptivity to love and beauty, and an awareness of the legacy they have inherited and are passing down. In a controlled trial published last year in Psycho-Oncology, patients participating in meaning-centered group therapy showed significantly greater improvements in spiritual well-being and less anxiety than those in traditional group therapy.

Experts also emphasize doing what one can to fight fear and stop ruminating. “When you diminish fear, you can be much more open to understanding what you’re dealing with and then find the best solutions for you,” says Ellen Stovall, senior health policy advisor of the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship.

Stovall speaks from experience—she was diagnosed with advanced Hodgkin’s lymphoma in 1971, when she was 24, and a cognitive behavioral therapist trained her to conquer her intolerable anxiety. “My fears were punishing me more than the cancer, which was being taken care of,” she says. The therapist gave her a dog-training clicker and instructions to click it whenever she found herself ruminating about what might go wrong, then force herself to do something else, such as baking or taking a walk.

Beyond redirecting anxious thoughts, there’s a place for full-fledged distraction to help avoid dwelling on a part of life that’s scary. “Distraction isn’t necessarily a maladaptive coping strategy,” Bellizzi says. “I like to think we have different tools in our toolbox for different situations, and distraction is one of those.”

For Luc Vautmans, a 44-year-old aerospace engineer and father of three, pursuing high-adrenaline activities has served a dual purpose of shifting his thoughts away from his cancer and increasing his sense of control. In September 2013, a small melanoma that Vautmans had had removed from his ear seven years earlier was found to have spread to his lungs, liver, gallbladder, and lymph nodes. There were about 40 tumors in all. He was told that he might have three months to live.

His first reaction was gallows humor: “These doctors know I have only three months to live, and they make me sit an hour in their waiting room?” Then he spent weeks fired up in anger, though as he responded to treatments, including immunotherapy, his mood shifted. He focused on being with his family and doing the kinds of high-energy activities he’d always loved, but even more intensely—upping the frequency of his alpine skiing, skydiving, motorcycling, and traveling.

“My basic idea was, ‘Let the doctors take care of the experimental drugs, and I’ll take care of my brain,’” he says. “Instead of going on one skiing trip a year, I went on seven.” Vautmans believed that he might be able to “convince” his body to fight the cancer by demonstrating that he had a strong will to live; if that didn’t work, at least he would have enjoyed his last days. He sailed past his three-month prognosis on to six, then nine, then a year. The physical activity prevented him from ruminating, particularly at night. “If you’re worried that you’re going to die in the next couple weeks, you lie awake at night thinking, What will happen to my wife and kids? But if you go skiing all day, you fall asleep in the evening.”

In addition to controlling their thoughts, people with chronic cancer are encouraged to take an active part in controlling their physical health and treatment. Robust self-management is what Slocum credits for his near decade of living with terminal cancer. In addition to his focus on nutrition and exercise, he has become a super-effective disease manager, entering all of his tumors into a spreadsheet, keeping up on the latest scientific literature discussing drugs in development, flying around the country to solicit second opinions, and readily questioning his doctors if he disagrees with a diagnosis or plan. “They make suggestions, but I make the final decision about what’s going on with my health,” he says. “They don’t have skin in the game the way I do.”

As for that which is beyond his control, the possibility of death is never far from Slocum’s mind, yet he quarantines such thoughts and focuses on the positive. “In all respects, I feel incredibly blessed,” he says. “People go, ‘Aren’t you mad?’ I’m not. I think about how lucky I am to be alive instead of how unlucky I am to have cancer. That doesn’t mean I don’t have bad days or doubts. It just means that I accept the hand I was dealt. I don’t know what the next chapter will bring, but I’ll do my best to deal with it. I have three kids. I’ll never give up.”

Submit your response to this story to letters@psychologytoday.com. If you would like us to consider your letter for publication, please include your name, city, and state. Letters may be edited for length and clarity. For more stories like this one, subscribe to Psychology Today, where this piece originally appeared.