Grief

We Heal From Grief in Relationship

An interview on the power of connection with novelist Tomas Moniz.

Posted June 3, 2024 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Key points

- Despite the cultural expectation of withdrawal, we often heal from loss in relationship.

- We don't "move on" from grief, but we can learn how to make room for it.

- Friendship and other social support are keys to resilience.

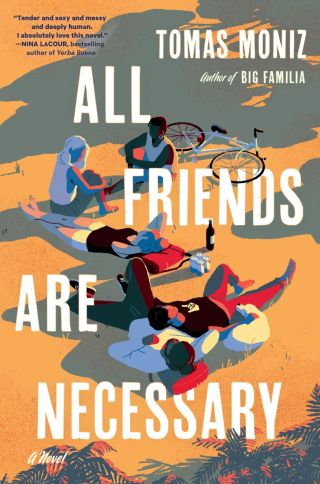

Oakland, California writer Tomas Moniz’s new novel, All Friends Are Necessary, might not be a “psychological thriller” in the traditional sense of that phrase but that’s the way I think of it: A platonic, romantic, funny, sexy, and thrilling story that follows the trajectory of the intense psychological journey of grief.

Moniz challenges the notion that we heal from loss in solitude. Rather, his characters find healing in relationships—friendships, hook-ups, and connections of all kinds. In the aftermath of my own wife’s death, it was just the summer read I’d been looking for.

Ariel Gore: You and I have both experienced deep grief in the last few years. In my own life, I’ve really appreciated the friends who've reminded me since my wife died that even though there’s a pull toward isolation—and a social expectation of isolation—we also heal in relationship. All Friends Are Necessary feels like a celebration of that truth.

Tomas Moniz: That’s so true. The expectation is that we grieve alone: Don’t leave, don’t go to work, don’t engage with others. I do think some of that is necessary, but for me and my family the most powerful moments of grieving as well as healing happened when we were in the vicinity of each other: cleaning up or holding the baby or doing the dishes while someone else swept the floor or took out the trash or made a meal: The work of living and healing. In many ways that kind of work never really ends; it evolves and changes as does grief, as do our stories.

AG: I love that your character, Efren "Chino" Flores, is so sexual. I think there’s a taboo around grief and sex, but Efren—who has just suffered an incredible loss of both his unborn child and his marriage—just seems to go with what he needs. Did you or he struggle with that at all? Or is it just that you and Chino are male and I’m female, LOL?

TM: I’m glad you’re pointing out those taboos around how we grieve because the first half of the book was written as an attempt to grieve the election of Trump. I needed to lose myself in silliness and sexiness to find joy in artistic creation and activism because what’s the point of this work we’re doing when someone like that can be elected president? When I began expanding that section to the more personal story of grief Efren faces, silliness and sexiness still worked because how often do we lose ourselves in slightly problematic behaviors as a way to deal with the pain whether it’s drinking or anger or hooking up?

AG: Another way you show the experience of grief so vividly is in the way that all of Efren’s friends seem to know about his loss, but there’s often a tenderness and a tension around whether anyone can or will say anything about it. Few want to bring it up. And Efren is just going through his new daily routines, work, and friendships and dating, and we can see him as a regular guy who is not also grieving and yet it’s always there. Sometimes in pangs and sometimes just as a ghost in the back of his mind. Can you talk more about exploring this aspect of grief?

TM: In All Friends Are Necessary, I tried to capture just how often and how randomly grief pops up, how it clouds your mind, tenses your body. For Efren, anytime the word “child” or some mention of childhood came up, it would stun him. He had to learn how to navigate that reaction—at times to push it aside, at other times to share with people what was going on in the moment. I think the key for me was to show his evolution, not to move on from grief (because we never do) but to learn how to make room for it, which allows him to learn how to offer support to others.

AG: Chino also turns to the natural world for healing —

TM: There’s a saying from teaching that I’ve always carried with me: When you’re stuck, drop what you’re doing and help someone else. Now I see how applicable that statement is. In the midst of my family’s grief, I realized I was obsessing over my house plants, where in the house they were happy, the amount of water they were getting. I was healing myself by taking care of something else.

AG: There is a poignant moment in your book when Efren’s best friend, Metal Matt, says, “A lot of people go through what you did, and it’s not the end of the world.” It’s a tense moment—Metal Matt is usually all compassion and deferring to what Efren wants to say about his grief—but that line did put a finger on a truth about death and grief: It’s completely commonplace. Everyone we love will die. And at the same time it’s personally nearly unbearable and culturally nearly unspeakable. I see All Friends Are Necessary as opening the conversations.

TM: I love this final question because I do think there’s this weird sense of guilt that at some point you need to just get going, get over it, get back to life. And yet can you ever? However, there is a strength in understanding that as much as it feels so individual, grief is a very common experience. To be able to let grief shape how you move through the world (rather than prevent you from moving) can be a really powerful, strangely bittersweet freedom. When I’m running around with my grandchild knowing that things will change, that there will be a time I no longer will do this, it allows me to celebrate that ridiculousness, to revel in my friends’ wild and singular selves, to lean into the joy of being alive with others.