Law and Crime

What Are “Son of Sam” Laws?

These laws are designed to keep felons from profiting from their stories.

Posted May 19, 2021 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- Son of Sam laws keep convicted felons in many states from profiting from the publicity of their crimes.

- The New York State Son of Sam law was struck down in 1987 when publisher Simon & Schuster claimed the law violated their First Amendment rights.

- Forty states still have Son of Sam laws on the books but their enforcement is inconsistent.

The so-called Son of Sam laws keep convicted felons in many states from profiting from their crimes by selling their crime stories directly to book publishers, film producers, television networks, etc. The Son of Sam laws are based on a premise that when you commit crimes, you lose certain rights and privileges, including the ability to sell your story.

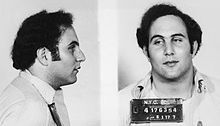

While one would not normally associate the serial killer David Berkowitz with First Amendment rights, legal expert and scholar David L. Hudson, Jr., explained that this is, in fact, the case (1). Named after Berkowitz’s serial killer alter ego, the Son of Sam laws are designed to take money earned by convicted criminals from expressive or creative works (e.g., books, films, TV shows, etc.) about their crimes and give it to their victims or the family members of their victims. The following is informed in part by the expert critique of the Son of Sam laws offered by David Hudson.

The Son of Sam laws were passed as a direct result of the celebrity criminal status attained by the serial killer David Berkowitz. In 1977, after hearing reports that Berkowitz was being offered a large sum of money for the rights to his personal story, the New York State Assembly passed a law requiring that a convicted criminal’s income from creative works describing their crimes must be deposited in an escrow account. The funds from the escrow account are then to be used to reimburse crime victims and their families for the harm they have suffered. Supporters of the laws say that they help crime victims and prevent convicted offenders from profiting from their crimes. Opponents counter that the laws infringe on fundamental First Amendment principles and rights.

Following the example established by New York, more than 40 states eventually passed Son of Sam laws. In a number of high-profile instances, however, state supreme courts have struck down their Son of Sam statutes for being unconstitutional because they restrict freedom of speech. For example, the Nevada Supreme Court struck down its Son of Sam law in a constitutional challenge filed by former prison inmate Jimmy Lerner, who wrote the popular memoir, You Got Nothing Coming: Notes From a Prison Fish.

Lerner had served three years in prison for a voluntary manslaughter conviction following the suffocation death of his friend Mark Slavin in a Reno, Nevada, hotel room in 1997. Slavin’s sister, Donna Seres, filed a lawsuit in August 2002 to collect profits from Lerner’s book. In January 2003, a Nevada trial court judge dismissed Seres’ lawsuit on First Amendment grounds. Lerner’s attorney, Scott Freeman, explained the verdict when he said:

"The [Nevada] law is content-based. It is very clear that these laws chill free speech. They not only violate the First Amendment rights of people like Mr. Lerner who engage in expressive work, but people also have a constitutional right to read books like his and receive information" (2).

The trial court judge in the Lerner case relied on a U.S. Supreme Court decision from 1991—that is, Simon & Schuster Inc. v. New York State Crime Victims Board—to support his decision. The Nevada Supreme Court subsequently reaffirmed the lower court decision and struck down the Son of Sam law, relying once again on the Simon & Schuster precedent.

The Simon & Schuster Decision

What exactly is the Simon & Schuster Supreme Court decision and why is it important? In 1987, the state of New York attempted to enforce its Son of Sam law after organized crime figure, Henry Hill, entered into a contract with major publisher Simon & Schuster to tell his life story. This relationship led to Nicholas Pileggi’s acclaimed book, Wiseguy: Life in a Mafia Family, which was later made into GoodFellas, a blockbuster Hollywood film starring Ray Liotta as Henry Hill.

The state of New York ordered Simon & Schuster to suspend all royalty payments to Hill as mandated by its Son of Sam law. The publisher sued the state claiming a violation of its First Amendment rights. The case eventually reached the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled in 1991 in Simon & Schuster Inc. v. New York State Crime Victims Board that the New York law indeed violated the First Amendment.

The U.S. Supreme Court voted unanimously to strike down the New York State law, finding that it was an overzealous and excessive attempt to protect victims’ rights. The Court noted that “a statute is presumptively inconsistent with the First Amendment if it imposes a financial burden on speakers because of the content of their speech.” The Supreme Court further noted that the law was “content-based” because it applied only to works with a particular content.

In First Amendment jurisprudence, according to David Hudson, content-based laws must be justified by a compelling state interest in a narrowly tailored way. The Supreme Court found that state officials had a compelling interest, stating, “There can be little doubt, on the other hand, that the State has a compelling interest in ensuring that victims of crime are compensated by those who harm them.” The high court also found that the state had a compelling interest in preventing criminals from profiting from their crimes.

Nevertheless, in striking down the New York Son of Sam law, the U.S. Supreme Court determined that it was too broad or “over-inclusive” (3). The law broadly defined a “person convicted of a crime” to include “any person who has voluntarily and intelligently admitted the commission of a crime for which such person is not prosecuted.” The New York law applied to creative works about crime even if the discussion about it was tangential or incidental to the work as a whole.

The Supreme Court reasoned that the New York law, as it was written, could apply to The Autobiography of Malcolm X, Henry David Thoreau’s Civil Disobedience, or even Confessions of St. Augustine. A list of prominent figures whose “autobiographies would be subject to the statute if written is not difficult to construct,” Justice Sandra Day O’Connor wrote for the Supreme Court. Justice O’Connor further wrote:

"That the New York Son of Sam law can produce such an outcome indicates that the statute is, to say the least, not narrowly tailored to achieve the State’s objective of compensating crime victims from the profits of crime" (4).

O’Connor emphasized that the decision affected only New York’s law and did not affect similar laws passed by the federal government or other state governments. “Some of these statutes may be quite different from New York’s and we have no occasion to determine the constitutionality of these other laws,” Justice O’Connor concluded.

In summary, the constitutional hurdles imposed by the Simon & Schuster decision are quite high. Following the decision by the Supreme Court, many states, including New York and California, amended their Son of Sam statutes. The amended California law is a bit narrower than the New York law that was ruled unconstitutional. California’s statute applies only to persons actually convicted of felonies and exempted those works that had merely “passing mention of the felony, as in a footnote or bibliography.”

Several other state supreme courts have invalidated their own Son of Sam laws entirely on First Amendment grounds. The clear message from these decisions is that legislation must be narrowly crafted to survive constitutional challenges. As concluded by David Hudson, it is evident that states must clear high First Amendment hurdles before targeting the expressive works of criminals on the basis of the content of their speech (5). Forty states still have Son of Sam laws on the books but their enforcement is inconsistent.

References

1) Hudson, D.L., 2004. “Son of Sam Laws.” First Amendment Center online.

2) Ibid.

3) Ibid.

4) Ibid.

5) Ibid.