Happiness

Santa: Reality and Imagination. What Does It All Mean?

What are the different layers of meaning in Santa's story?

Posted December 11, 2012

Traditions are full of meaning that is often lost as the centuries roll by. We have bits and pieces of a story. How do we make sense of the pieces we have? Who was Santa Claus? Historically, we know very little about him; but his story has continued to grow over the centuries. He was a third century Greek Christian in Turkey, a monk who was elected Bishop of Myra. An orphan of wealthy parents, he is known especially for his charity to the poor.

His story gradually spread from East to West. In the 11th century, after the Byzantine Empire fell to the Selijuk Turks, Italians took not only his story but also his bones to Italy for safekeeping. Because of the stories associated with him over time, Saint Nicholas is known as “the Miracle Worker.” He is the patron Saint of Greece and Russia, as well as children, sailors, bankers, travelers, and young marriageable girls, among others.

In different languages, his name changes a bit. In Dutch, St. Nicholas became Sinterklass, which, in turn, became Santa Claus here in the U.S. His name was muddled even more when Martin Luther, father of the Protestant Revolution, did away with all the saints, including Saint Nicholas, and had the Christ Child, Chriskindl, deliver the Christmas gifts, which eventually led to the confusion of Saint Nicholas with Kris Kringle.

The Santa Americans know and love was first described by the biblical scholar Clement Clark Moore in a poem he wrote in 1822 for his children—“A Visit from St. Nicholas” better known as “Twas the Night Before Christmas. “The American illustrator Thomas Nast made his first beloved illustrations of Santa for Harper’s Weekly in 1862 during the Civil War to honor sacrifices of northern families during the struggling Union effort in which Nast so strongly believed. (Ironically, Clement Moore was a slave owner against abolition.)

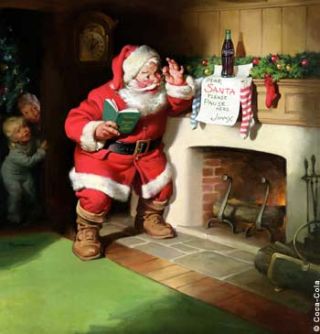

After 1880, when the country had recovered a bit from the Civil War, New York and other cities began the commercialization of gift exchanges at Christmas. Nast’s popular illustrations were gathered in one book in 1890. Santa’s image became what we know it as today thanks to the paintings for Coca-Cola Christmas advertisements beginning in 1931 by illustrator Haddon Sundblom, a Swedish-American.

Stories that foster the imagination develop creativity, self-confidence, and empathy. Today when school administrators think reading more instruction manuals than novels will help develop smarter students, we would do well to remember what Einstein said, “Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited, whereas imagination embraces the entire world, stimulating progress, giving birth to evolution. It is, strictly speaking, a real factor in scientific research.”

The story of Santa presents a wonderful opportunity not only to talk with kids about the importance of imagination and different layers of meaning in stories and symbols, but also to think about those topics ourselves as adults.

Growing up is hard to do. Finding out about Santa’s gift giving strategy, however, should be a new beginning and not the end of his story for kids and adults. What do we like the most about him? Tell the kids his history if they don’t already know it; and ask them why they think his story was carried across the world? Why it endures? What he represents? What are their favorite Christmases and why? Can his life be an inspiration for how we live ours?

That question reminds me of what my father-in-law Charles Waugaman once said, “It’s too bad people don’t realize that it’s not what you get, it’s what you give that makes you the happiest in life.”

The story of Santa also offers the opportunity to discuss the multiple layers of meaning in stories. The first level is simply the literal meaning. In the case of Santa, the story is literally that of a jovial, little, fat man who delivers toys to children on Christmas. This leads to the question of what we know about all the stories we read and hear. Do we know everything? Are pieces missing? (Most Americans don’t know about the historical Santa.) Who is telling the story? What is their point-of-view? How does their point-of-view affect the story they are telling?

St. Nicholas was so appealing that new stories sprang up about him all over the world. Why? Santa fulfills our desire to help others and to make wishes come true—a little piece of paradise for one brief sparkling moment.

Another level of meaning appears when we start asking questions about what is the value of a story—the moral lesson we can draw from it. From Santa’s story we learn about altruism, generosity, empathy, and the power of the imagination.

A third level of meaning would be the spiritual meaning of a story that surpasses the simpler moral lessons—that all mankind is connected, that the greatest gift is what we do for someone else. Stepping outside of the self allows us to find meaning; for it is only by what is outside of us—what we give to others and how we relate to them—that we can be truly known. Otherwise, we are simply a display case of no value to anyone, even ourselves.

The story of Santa reveals that truth is complex and multifaceted, not one dimensional. It’s like the Indian story of the four blind men and the elephant. Each could only describe the part of the elephant he had touched, so each blind man had a very different idea of what an elephant was. To know what an elephant—i.e., the truth— is, you have to connect all the stories. Mankind has a wonderful world of stories to share. We can learn from all of them.

Best wishes for the holiday season and the New Year. May they be filled with wonder, imagination, complexity, and generosity.