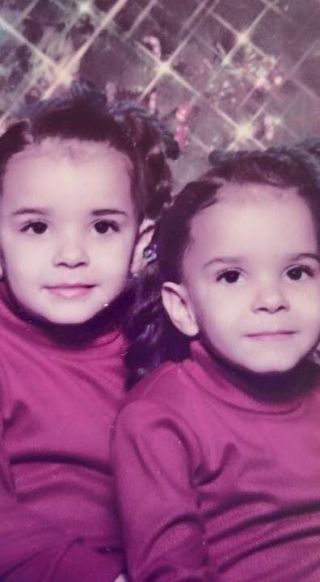

Understanding Twins

The Unique Development of Twin Language

How to prevent communication problems between twins and non-twins.

Posted March 13, 2024 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Twins develop language very differently than single children because of their profound relationship with each other. Early language acquisition in twins is very crucial to the development of their individual identities and their twin identities. Many psychologists and twin experts contemplate why learning to talk for twins is such a concern and a complicated problem. There is no agreed-upon answer to this unusual and problematic developmental issue. In reality, when speech development is left unattended, lifelong problems with communication are inevitable for twin children. For example, twins can be reluctant to meet new friends and colleagues, or just not have the skills to do so.

Many twin researchers suggest that underdeveloped language in early childhood is related to the “twin situation,” that is, being a twin. Because twins are so close to each other they often communicate non-verbally or understand what their twin is going through without the use of words. More simply stated, sometimes twins do not need to learn to speak, because they just understand each other, as their egos or sense of themselves are intertwined.

Twin co-dependence on each other as they learn language creates other specific problems. When twins do not have enough time to talk to other people on their own because their parents are not attending to separating them, they miss the crucial experience of communicating without their twin’s presence. And from my own personal experience, and from consulting with so many twins and their parents, I assure you that young twins are more comfortable meeting and talking with new people when they are together. Being apart as children in new situations can be very difficult.

In very young twins, the development of a confusing verbal relationship and communication can be easily observed. Parents also comment that they cannot understand what their very young twin children are talking about or fighting about. The very young twins understand each other without words. The mind-reading phenomenon of twins often leads to a secret language as word usage develops. I consulted with a set of twins who were hardly ever apart as children and had difficulty learning to talk to people who were not their twin. Too much time in each other’s presence can make it extremely difficult to prevent underdeveloped language skills. When parents talk to their twins individually a great deal, the danger of being awkward talking to others beside their twin is less likely. Talking to each child separately is very time-consuming and hard to do, as twins like talking to each other. Twins understand each other easily and do not feel ignored or misunderstood as they do with new people.

As twins grow older, problems with language acquisition become more socially focused. When separation and individuation are experienced because parents take the time to promote individuality, learning to communicate with non-twins is less difficult. Often, twins who are behind in learning to talk will be too reliant on their twin in school or will protest going to school. I consulted with a set of 25-year-old twins who shared with me that their closeness created social inhibitions. They only spoke with each other until the school required them to go to speech therapy to learn to talk with other children. This intervention was very helpful. They attended speech therapy for three years and were finally able to speak to other people without their twin present.

What is interesting and maybe counterintuitive is the reality that the strength of the mother-child relationship and its uniqueness with each twin is an important determinant of the children’s ability to want to talk to other people besides their twin. It is not unusual for twins who have not had enough separate experiences without their twin to be frightened to go to school, and in some cases, to refuse to go to school. Parents who do not understand the dangerous side effects of too much closeness can make the twin language problem more serious by thinking that twins should always go places together. For example, one twin is invited to a party and the mother asks if the other twin can go. This is the wrong intervention. Twins should not always go together.

Twins Communicate More Intensely Than Other Children

The language problem and speaking awkwardness continues in different ways as twins grow up.

It is not unusual for twins to be unable to explain themselves to other people even if they are capable students at school and in structured situations. I had this problem myself well into my adult life. When in training, my dear friend would say, “I think you have a sentence completion disorder; you need to finish this idea.” Maybe I still believed that my sister would bail me out. I think I am better at writing than talking in some situations. Believe me, learning to talk with non-twins is a hard problem to solve.

What Parents and Teachers Can Do to Promote Language Use for Twins

Language usage will develop in an optimal way if the following parenting interventions are used on a daily basis.

- Talk to each of your twins separately.

- Do not allow twins to take care of each other for your convenience.

- Plan almost every day for twins to have separate experiences alone or with other people.

- School experiences should allow for separation that twins can tolerate.

- Parents have the final decision on when to separate their children.

References

I am starting a twin parenting group that will discuss what I have found to be useful when raising twins. The group is open to parents of twins of all ages. Reading for the class will be optional, but encouraged. If you are interested in more details, please email me with your contact information: drbarbaraklein[at]gmail.com