Cognition

The Healing Power of Poetry: Appreciating a Primal Pleasure

Recent studies demonstrate poetry’s power to soothe.

Posted April 27, 2023 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- Poetry reconnects us with the beauty and goodness of the world while also naming its difficulties.

- When we read a poem that speaks to us, we realize we are not alone.

- One of our earliest and most fundamental pleasures as humans is the sensory delight of language.

.jpg?itok=DJxtEFst)

Uncertainty is a word that pops up frequently in conversations. The pandemic, gun violence, international conflagrations, and the escalating number of climate disasters have increased our concerns about safety and heightened our awareness of our inability to prevent or control many current challenges. Global and societal changes that affect us personally are occurring at an accelerating pace, often without warning. No wonder we’re invaded by pervasive anxiety and feelings of vulnerability and isolation.

We know that stress-reduction techniques like meditation, yoga, exercise, and walks in nature mediate the sympathetic nervous system’s stress response of fight, flight, or freeze. Another time-honored but much-overlooked modality that can restore a general sense of well-being is the reading and writing of poetry.

Poetry reconnects us with the beauty and goodness of the world, while also naming its difficulties. Rather than dismissing hardships, poetry calls them out and reminds us that others have also lost a loved one, experienced disappointments, endured sleeplessness, lived with depression—have suffered as we now suffer. Poetry allows us to identify our personal turbulences, breaks our feeling of isolation, and affirms our sense of belonging. Poetry steers us toward wisdom and acceptance.

Science agrees. The International Arts & Mind Lab at Johns Hopkins University offers convincing evidence from a number of studies that poetry is good for our health.1 A 2021 study at a Rhode Island hospital found that hospitalized children who read or wrote poetry experienced decreased negative emotions such as fear, sadness, anger, worry, and fatigue.2 Another study from 2013 in the Philippines showed that guided poetry writing sessions significantly lessened depression in a group of traumatized and abused adolescents.3 Reading a poem that speaks to us, we realize we are not alone.

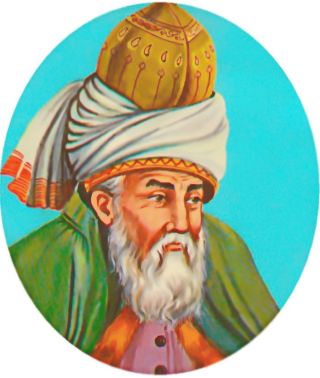

Consider “The Guest House” by Jalal al-Din Rumi, a 13-century Sufi mystic and one of the most cherished poets today. Written more than eight hundred years ago, the poem invites us to view all of life's experiences and the feelings that arise from them as temporary visitors in the "guest house" of self. With patience and compassion, Rumi counsels us to recognize that even negative moods are precious teachers for our growth.

In The Body Keeps the Score, Bessel van der Kolk describes the effects of traumatic stress on the mind and body. I suggest that the body keeps the score on pleasure, too. One of our earliest and most fundamental pleasures as humans is the sensory delight of language. The lullabies, rhymes, and nightly prayers of our youth linger in the recesses of our brains. Some of us wished upon stars: Wish I may, wish I might, make this wish come true tonight. Some of us played clapping games: Miss Mary Mack, Mack, Mack/all dressed in black, black, black. Some of us made up silly limericks: A flea and a fly in a flue/Were imprisoned so what could they do/Said the flea, let us fly/Said the fly, let us flee/So they flew through a flaw in the flue.

A 2019 study in Finland measured the surface brain activity of 21 newborn babies listening to regular speech, music, and nursery rhymes. Only the nursery rhymes produced a significant brain response when the rhymes were altered, suggesting that the infants’ brains were trying to predict what rhyme should have occurred.4

Our innocent delight at nonsensical rhymes and metrical rhythms brings a smirk now, but as children, those sounds provided sensorial pleasure to our tongues, lips, and ears. In a 1978 essay called “Goatfoot, Milktongue, Twinbird: Infantile Origins of Poetic Form,” the poet Donald Hall identified the origins of poetic form in the preverbal babbling of infants, in the mouth-pleasure of sounds and sucking, and muscle-pleasure of clapping, tapping, and repetition.5 (When faced with a cranky baby, try a round of peek-a-boo, repeating the word itself, or cradling the baby while swaying and singing a rhythmic tune.)

We have forgotten how intimately we are connected to poetic meter, Iambic pentameter, the ta-DUM ta-DUM ta-DUM of one unstressed and one stressed syllable in a five-beat line, mimics the percussive beat of our hearts. In his ground-breaking book, The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World, Iain McGilchrist cites numerous instances of how, across cultures, people display a general appreciation for art, including poetry, which suggests that the brain has a non–socially constructed intuitive capacity to apprehend “beauty and the understanding of its expression through art.”6

Are we somehow aware that there is something beyond its grasp? The great Swiss depth psychologist Carl Jung believed we have an inherent desire to connect with the deeper mysteries of existence, what he called “the religious attitude,” that creates a bridge between our inner world and the vast boundless outer one.

Especially during times of need, poetry acts as a bridge and invites us to participate in a greater understanding of our travails, and awakens our perceptions to beauty and joy, right here, right now. In “The Summer Day,” Mary Oliver calls out praise for the natural world and urges us to find our place in the natural order. Like Rumi, she asks the reader to recognize life’s preciousness and encourages us to consider how we might make the most of that precious gift. Mary Oliver once said, “I got saved by the beauty of the world.” This is the advice her poems offer us, to approach all experiences with gratitude and wonder.

Think of poetry as a portal to a timeless place where we find solace, companionship, enlightenment, enchantment, mystery, connection, wisdom, humor, and healing. Poetry, especially contemporary poetry, names the disconnects as well, where we have gone blind to existential threats and personal sorrows that threaten to overwhelm us. With its adherence to the precision of language, its concision of thought and meaning, and its naming and interrogation of experience, poetry, in a small space, usually one page, packs a wallop.

To enter a poem is to escape the clamor of the ordinary world. Poems can be reminders of things we know but have forgotten. Painful experiences are reframed and given a new understanding by a poem. That’s because poetry reflects a rich brew of the sweetness and bitterness that is life. It refreshes our temporal minds and offers invented landscapes of imagery.

Rumi and Mary Oliver lived centuries apart and yet they speak to each over, and to us, across time. It’s a long way from "Hickory Dickory Dock" to T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland, but a direct line exists between the formal poem and our wiring for pleasure in pattern, rhythm, and form. Poetry is not an escape from but an escape to a place to land, a refuge.

For your own health and peace of mind, I encourage you to take up a friendship with poetry.

References

1. Sima, Richard, “More Than Words: Why Poetry Is Good for Our Health,” International Arts + Mind Lab (IAM Lab), Johns Hopkins Medicine, March 11, 2021

2. Chung, Erica et al., “Effects of a Poetry Intervention on Emotional Wellbeing in Hospitalized Pediatric Patients,” Hospital Pediatrics, American Academy of Pediatrics, March 1, 2021

3. Brillantes-Evangelista, Grace, “An evaluation of visual arts and poetry as therapeutic interventions with abused adolescents,” The Arts in Psychotherapy, February 2013.

4. Suppanen, Emma, et al., “Rhythmic structure facilitates learning from auditory input in newborn infants,” Infant Behavior and Development, November, 2019.

5. Hall, Donald, “Goatfoot, Milktongue, Twinbird: Infantile Origins of Poetic Form,” in Goatfoot Milktongue Twinbird: Interviews, Essays, and Notes on Poetry, 1970-76 (Poets On Poetry), University of Michigan Press, 1978.

6. McGilchrist, Iain, The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World, Yale University Press, 2019.

Poetry Resources: Poetry Foundation, Academy of American Poets, Poetry International