Anger

Murray Stein on Understanding and Coping With Anger

Part 2 of a conversation with Jungian analyst Murray Stein about anger.

Posted June 25, 2021 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Like most young girls of my generation, I was raised to be kind, considerate, and quiet. The message was clear: Anger was verboten and had to be squelched. Or else.

Learning how to transform and transmute anger begins early and engages us throughout our lifetime. We may try to control anger, but in many instances, anger has a mind of its own. Anger combusts spontaneously. It arises on its own timetable and under its own conditions, sometimes for reasons our conscious minds can’t decipher.

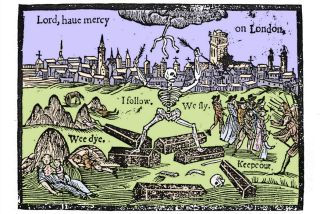

Images of anger haunt our imagination. Visions of apocalyptic fires appear in our earliest literature. Myths and fables and folktales serve as precautionary warnings that forces outside our control can throw down thunderbolts or cause villages to go up in flames.

How do we explain anger’s force and prevalence? How can we cope with its destabilizing energy?

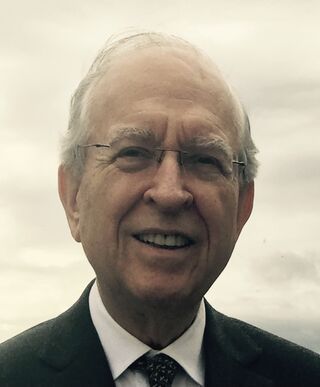

In this second installment on anger, my guest, the distinguished Jungian analyst and acclaimed author Dr. Murray Stein, expands our discussion: how anger is showing up in our inner and outer lives and how, when examined closely, anger relates to feelings of vulnerability and despair.

Dale Kushner: Is the anger you are seeing in your patients related to their age? What do you think is causing this eruption of anger?

Murray Stein: I am seeing anger in patients of all ages. If they are young, they are angry about being denied the normal path to educational experiences because of the pandemic. If they are old, they are angry because of the insensitivity of the young about their vulnerability to COVID-19. And so forth. Anger is present in every age group, and for similar or different reasons, some stimulated by the pandemic, some by the political conflicts raging in almost every country of the world, some by economic disadvantages and vulnerabilities. No age group is free of anger these days.

DK: Are there redeeming aspects of anger? What might they be?

MS: Anger can be the prelude to necessary change. It motivates one to act, and sometimes this is needed for development. Anger can lead to necessary changes in life if it is channeled in a direction that is constructive in the long term.

A battered woman in an abusive relationship who uses her anger to change her situation is for the good and in the interest of individuation if it leads to greater consciousness and self-affirmation. As a psychotherapist, I am pleased when a depressed and passive client becomes angry and stands up for herself. Anger can serve the goals of psychological development and individuation. It demands that things change.

DK: What is the value of dreaming about anger? Is it cathartic? Does dreaming about anger help a person process it?

MS: Dreaming about anger means that it is becoming conscious. Anger can simmer under the surface, on the fringes of consciousness. In the dream, it erupts. This signals the emotion is becoming conscious and can be felt and processed. Anger in a dream is anger on its way to consciousness, and once conscious, it can be worked with and does not get expressed by acting out.

DK: What myths or fairy tales instruct us about anger?

MS: We can learn a lot from myth about the impersonal psychic forces that can take possession of our conscious selves, individually and collectively. For instance, in Greek myth, the chthonic Alecto, whose name means “unceasing in anger,” is a Fury conceived by Gaia when the semen from Ouranos was spilled into her when their son, Kronos, castrated his father. Alecto lives in the underworld and can be summoned to action, sometimes in service of justice for moral crimes committed and sometimes simply to instigate violent anger on behalf of a political cause.

In the Aeneid, she is sent by Juno to stir up furious anger in the Latins against the invading Trojans. In the narrative, you see how Alecto (relentless anger) invades and takes possession of humans and drives them to action that we would judge to be insane. She enters the body of the Latin Queen Amata, who incites the Latin women to riot against the invaders. Then she enters the body of Juno’s priestess, Calybe, and proceeds to incite King Turnus to go on a rampage against the allies of the Trojans and slaughter at random to the point of absolute exhaustion.

Virgil’s great epic tells the story of angry heroes battling over territory and the subsequent founding of Rome by the victor, Pius Aeneas. The Trojan hero stakes his claim in Italy at the command of the high god, Jove, and Venus, his mother. They tell him it is his destiny, and he must not settle for less than their ambition for him and his Trojan survivors from the fall of Troy.

The poem is generally seen as a celebration of Emperor Augustus and the establishment of the Roman Empire, but it is also a moral critique. Anger permeates the epic from start to finish, and the final climactic lines reflect the overall tone. It is a scene on the battlefield; Aeneas is standing over the wounded Turnus, who is begging for his life. I quote the closing lines in the fine new translation by Shadi Bartsch:

Aeneas drank in this reminder of his savage

grief. Ablaze with rage, awful in anger, he cried,

“Should I let you slip away, wearing what you

tore from one I loved? Pallas sacrifices

you, Pallas punishes your profane blood” — and,

seething, planted his sword in that hostile heart.

Turnus’ knees buckled with chill. His soul fled

with a groan of protest to the shades below.

From The Aeneid by Vergil, translated by Shadi Bartsch (Random House, 2021)

This is the end of the epic, and a bloody and angry ending it is. Empires are founded on such.

DK: Is there anything in popular Western culture that gives us remedial lessons about anger?

MS: In Jungian psychology, we try to bring opposites in contact with each other and wait for a uniting symbol to bring them together. What is the opposite of anger? In the Western tradition, its opposite is peace. In popular culture, there are many songs, films, TV shows, etc., that promote peace. They suggest putting anger aside and making peace. “Make love, not war” was a popular slogan in the '60s during the protests against the American war in Vietnam.

The problem is you have to want to choose peace over anger, which usually also means giving up the desire for power over the other. If there is injustice afoot, it is not easy to choose peace. Alecto may be summoned and stir up rage in an injured individual or population. The natural response to injustice is to become angry and to fight for change.

But there is another response to injustice, which the Quakers in America are known for with their efforts to cultivate peace even while being activists for social justice. They attempt to combine anger and peace in their protests and messages. Some individuals have found a way to contain anger and use it to fuel the peace movement. Others, of course, sink into depression and resignation.

DK: How did Jung think about anger? Did he relegate it to the shadow aspect?

MS: Jung reflected on the topic of anger as born of inferiority and resentment in his essay “Wotan,” where he writes about the social and political climate in Germany in the 1930s. He himself had a fiery temper and would occasionally lash out in angry outbursts toward opponents and critics. I think he would say anger was part of his shadow, which at times he could channel to constructive ends and at times not.

Barbara Hannah claimed that when Jung would get angry at her, it was also meant to teach her something and came as a lesson for improvement. She may have been rationalizing a bit. Basically, Jung would say that if you are possessed by an emotion like anger to such a degree that you lose control of your judgment, you have been taken over by a complex or archetypal energy. On a collective level, this archetypal energy is symbolized by mythical figures like Wotan or Ares/Mars. Entire masses can become possessed by these archetypal energies, and then you have warfare.

DK: To what degree do you think social media fuels or contributes to personal anger?

MS: Social media pours fuel on the fires that are already burning. A person is somewhat anxious and then gets messages that confirm the fears she is already feeling. This leads to angry responses, and the ball gets rolling. Social media intensifies the emotional tone of the times. I don’t think the answer is to cancel the media or ask them to tone it down. A better answer is to have leaders who show a better way forward. Social media is a follower, not a leader.

You can read Part 1 of this conversation with Murray Stein on the Eruption of Anger in Today’s World.