Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

What Really Determines Your Peace of Mind?

The Stoic philosophers of Rome and Greece got it right.

Posted July 18, 2019 Reviewed by Matt Huston

When I was a sulky teenager, my dad once told me that “attitude is the last freedom” (invoking Viktor Frankl). His point was that it was up to me whether I was miserable when circumstances weren’t cooperating the way I wanted them to. I found this bit of guidance liberating at times, but also irritating. Couldn’t I just be sullen when I didn’t get my way?

Now that I’m a sulky adult, I still often forget the key to true and lasting contentment. You probably do, too. Most of us invest all of our energy in trying to force outcomes we ultimately can’t control, and none of our efforts on the only sure path to peace of mind.

Stoicism and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

Our default belief is that our happiness depends on our situation. If we’re unhappy, it must be because something isn’t going right. If only things were better, then I could be happy. Accordingly, we tie our well-being to all kinds of things that are outside of us:

- Material wealth: a car, a house, your income, your clothing

- Prestige: fame, accomplishments, social standing, a job title

- Other people: their opinions of you, whether they agree with you, how they treat you, whether they appreciate you

- Other circumstances: politicians, the weather, the traffic, illness, how much sleep you got last night

“Just the world unfolding as it does can feel like some sort of injustice,” said Dr. William Ferraiolo, professor of philosophy at San Joaquin Delta College and author of several books on Stoicism (including his most recent, Meditations on Self-Discipline and Failure: Stoic Exercise for Mental Fitness). I recently interviewed Ferraiolo on the Think Act Be podcast where we explored the overlap between Stoic philosophy and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which has its roots in the Stoic teachings.

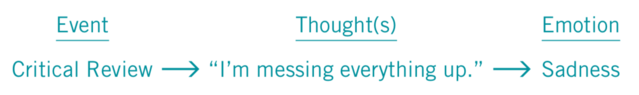

The key to finding true contentment, said Ferraiolo, is to “recognize the sorts of external events that tend to cause unpleasant psychological and emotional states.” This is exactly the approach we take in CBT, in which a person is invited to note the events that trigger painful emotions. I give the example of Susan getting a negative performance review in CBT Made Simple. At first pass, it seems that the bad review alone is what made her upset:

The next step is to look for the thought or belief that lays a path from the event to your emotional experience of it. “If you can identify the underlying beliefs and expectations,” said Ferraiolo, “typically you’re going to find irrational beliefs and unreasonable expectations.” Again, this is exactly the practice we encourage people to do in cognitive behavioral therapy. Continuing the example from the book, Susan figures out the interpretation of the event that upset her:

Once you’ve identified the trigger and the associated thought, you’re in a good position to take a hard look at the thought to see if it’s accurate. “If you can challenge those beliefs and expectations properly, you can diminish your suffering,” said Ferraiolo. “You can diminish the intensity of your anger, despair, etc., and also diminish the frequency with which you fall into those conditions.”

Another example: Imagine that you start getting sick the day before a big presentation or job interview you’ve been preparing for. If you’re like me you’ll probably think something like, I can’t believe this is happening—this is so unfair. The underlying belief is, This should not be happening to me. Not surprisingly, you’ll feel frustrated and probably bitter, and might believe that feeling contentment under these circumstances is simply not an option.

But if we take a look at those thoughts and beliefs, we’ll find that they’re not based in reality. Is it unusual to get sick, even on the eve of an important event? Is it a personal injustice? Does it exclude any possibility of happiness, equanimity, or even gratitude for everything else that is right in your life—including the fact that your body will heal?

Changing Perspective

We’re so used to assuming the way we feel is a product of our circumstances that it might seem strange to say that happiness doesn’t depend on those things. But a simple thought experiment shows that it’s true.

Imagine that you’re living your life, feeling vaguely disgruntled, perhaps a bit too hot or cold, and mildly disappointed about a couple of things that aren’t going the way you want them to. Just beneath your conscious awareness you blame your emotional state on what’s happening in your life and believe that you can’t feel contented until those situations improve.

Then imagine you learn that someone you love dearly might have a serious illness. You’re terrified that you might lose this person. And then, thankfully, you’re told it was a false alarm, and your loved one is well.

You immediately feel enormous gratitude for your life—which for all practical purposes is identical to the life you were unhappy about. You still have a healthy loved one, and you still have your life’s imperfections. The only thing that has changed is your internal experience and your awareness that things like our loved ones’ health are not guaranteed. (Thanks to Sam Harris, from whose lesson on mindful awareness I adapted this scenario.)

As this example shows, it’s really our internal perspective that is the final determinant of our well-being. Granted, external events may affect you—like having a massive head cold when you have to perform—and make it more challenging to find emotional equanimity. But ultimately the source of your happiness lies within.

Easy to Learn—and Forget

I’m often surprised by how easy it is to forget the principles from the Stoics, given how simple they are and how long they’ve been recognized. Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius lived in the first and second centuries CE. St. Paul, the writer of many New Testament epistles who lived around the same time, also seemed to espouse some Stoic principles—for example, “I have learned to be content whatever the circumstances” (Philippians 4:11). Buddha taught hundreds of years earlier and offered similar guidance: “Peace comes from within. Do not seek it without.”

Ferraiolo noted that the ideas of Stoicism can fade from general societal awareness, passing in and out of vogue over the years. He sees a resurgence of interest in these principles in the past couple of decades, with several popular books on Stoicism like A Guide to the Good Life and The Daily Stoic.

“The challenges of the human condition really haven’t changed that much over the past couple thousand years,” according to Ferraiolo. “Technology has changed, but we are still relatively small and frail and ephemeral, and the world is large and powerful and mostly takes no heed of our interests.” And like the Stoics, we still meet the same end. “The world is going to kill you,” said Ferraiolo, “and it’s going to beat the hell out of you between now and then.”

So why do we forget these truths? Ferraiolo blames the primitive parts of our brains. “The limbic system has been there longer than the prefrontal cortex,” he noted, “and it’s quicker and more powerful in many ways. If we’re not careful and attentive, it can send us into really powerful emotional states that are not conducive to good behavior.”

But as Ferraiolo found for himself, it’s possible to train the mind to respond differently.

Life-Changing (and Life-Saving) Practices

Ferraiolo said he was “a disastrous human being” for many years. “My two brothers and I inherited a fairly severe anxiety and depression disorder from our father,” he told me. “I lost one brother to suicide, and I may have been headed in that direction myself.”

He described himself as constantly angry, unable to sleep, and “not a pleasant person to be around,” with verbal and sometimes physical conflict a regular part of his days. “I was not at all happy or at ease, or comfortable in my own skin, and I had an enormous amount of pent-up nervous energy that I didn’t know what to do with.”

And then one day he came across the Discourses of Epictetus at a used book shop. After reading it for a few minutes, he realized it was what he needed. Since that time, Stoic practices have made an enormous difference in his life. “I’m now maybe only 25-30% as disastrous as I used to be,” he said. “I still have my dark moments. But now I can talk myself off the ledge, and get myself back to something like rationality and calm.”

Ferraiolo is now paying it forward through his own writings. I also found great relief in the principles of Stoicism when I first read an excerpt from his latest book. I was in a challenging period with my health and was feeling like my struggles precluded the possibility of contentment. Then I read these words:

“Everything that can suffer, does suffer. Everything that can die, will die. You have suffered, you will suffer much more, and a lifetime of your suffering will culminate in your death. When you can muster genuine gratitude for all of that, then you will have made the kind of progress that is not easily reversed. To develop sincere appreciation for this opportunity to be born in a brutal world, not of your making, to struggle and fail time and time again, to feel repeatedly lost, bewildered, frustrated, and hopeless, to swim in this ocean of misery, and, ultimately, to drown in it—this is the beginning of wisdom. You must embody overwhelming gratitude for the opportunity to fail repeatedly, with no guarantee of eventual success, and to wade cheerfully into a doomed struggle against time and your own limitations.”

While they weren’t easy words of comfort, I did find them deeply comforting; they brought tears to my eyes and a great sense of relief. I remembered that what I was experiencing wasn’t a personal tragedy, but instead an inescapable reality of existence.

“There will be bad days,” Ferraiolo said. “The world is a rough place.”

How to Get Started

Are you ready to benefit from Stoic teachings? Here are three keys to get you started:

- Be honest with yourself. If you’re going to make real changes, you need to see yourself clearly, including your limitations. “It’s difficult to develop an accurate assessment of oneself and one’s own character,” said Ferraiolo. “It takes brutal honesty about where we’re flawed and where we really need to work.” Acknowledge, for example, if you’re prone to feeling sorry for yourself or blaming your problems on others. Keep in mind that while the limitations are yours, they’re not personal. Like suffering, they’re a part of the shared human experience.

- Focus on controlling your own mind and actions. Leave aside useless struggles, like getting upset about the weather or the latest outrage by your political enemies. Ferraiolo recommends focusing instead on things that are actually yours to control. “Just by deciding that it be so, you can treat members of your family a certain way. You can govern yourself in a virtuous fashion.”

- Train your mind every day. It takes continual work to retrain yourself to respond differently to life’s challenges. Read a book like Ferraiolo’s or The Daily Stoic for daily reminders of the mindset you’re cultivating. “The Greco-Roman Stoics advised their students to have maxims at the ready,” said Ferraiolo—“brief, pithy reminders that they could recall at those moments when they most needed them. So even the masters who devoted their lives to this had to frequently remind themselves, ‘OK, listen, you’re angry, and that’s not going to help.’”

The full interview with Dr. Ferraiolo is available here: “How to Train Your Mind Like the Stoics.”

References

Ferraiolo, W. (2017). Meditations on self-discipline and failure: Stoic exercise for mental fitness. Croydon, UK: O-Books.