Career

You Can Have It All

The hidden benefits of engaging in both work and family

Posted July 1, 2014

The poster for the 1987 comedy “Baby Boom” shows Diane Keaton as a high-powered working mom in a suit and high heels, awkwardly balancing a baby on her hip and gripping a briefcase in the other hand. Her purse strap cuts uncomfortably across her chest. She looks loaded down, worried, and uncertain. How will she manage to juggle work and family? What will she have to sacrifice to do it?

The image was iconic for the time: the filmmakers clearly knew that people would recognize and respond to the struggling-working-mother theme. But what strikes me is that, although more than 25 years have passed since that movie was made, we are still asking the same basic questions—and making some of the same assumptions—about women, work, and family.

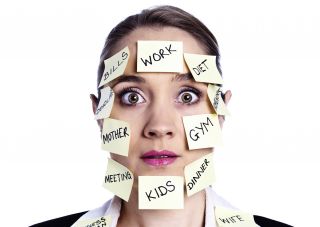

A glance through recent articles and blogs in media reveals that the popular press continues to frame the discussion about women and work in largely negative terms, or what psychologists call “depletion.” Women have to “juggle” or “balance” work and family. They’re stressed and exhausted by the struggle to “have it all,” and guilt-ridden about not measuring up. And women can’t be effective on the job because they are constantly “distracted” by home issues.

Even much of the scholarly literature has trod a similar path. Traditionally, researchers in this area have worked from an underlying assumption that family engagement (engagement meaning being “psychologically present” in what you are doing) is typically achieved at the expense of work. As a result, they’ve tended to focus on the depleting aspects of work-family balance such as time drain, stress, and conflict.

Nobody ever said that having a full, busy life was easy. But the simple formula of conflict and depletion seemed to tell only part of the story. Did the scenario have to be uniformly negative? Were there ways in which dealing with work and family—for women and for men—could be psychologically “okay”? Or even complementary? Or—I theorized—enriching?

In my study, “Enriching or Depleting? The Dynamics of Engagement in Work and Family Roles,” I surveyed 790 employed women and men about work and family issues. What I found was evidence for both enrichment and depletion. I also discovered some strong gender differences.

Both men and women experience enrichment. However, they experience it differently. When men have positive work-related emotions, it tends to enhance their engagement with family. Conversely, when women have positive family-related emotions, it tends to enhance their engagement with work. This would indicate that having a family is not an inevitable drain on women’s job effectiveness. In fact, it can be energizing rather than enervating.

As far as depletion, on average men did not experience it. In the study, strong engagement with work did not reduce their family engagement, and strong engagement at home did not reduce their job involvement. They appeared to have the ability to “check their problems at the door.”

The sole evidence of depletion occurred only for women, and only in the work-to-family direction. For example, if a woman feels dissatisfaction because of her job, it can negatively impact her focus at home. This might stem from the fact that women are more likely than men to “ruminate” (focus compulsively) on negative events (Nolen-Hoeksma, 1987.) They also have more synergistic models of work and family roles than men (Crosby, 1991; Andrews and Bailyn, 1993) which allow both good and bad experiences to spill over from one role to another.

But for whatever reason the depletion occurs, it’s notable that, on average, women tended to bring negativity from work to home, but not from home to work. Employers’ concerns that women will let family problems overburden them are not well founded. In fact, since a robust family life might enrich women’s worklife, organizations could perhaps reap benefits from supporting family involvement.

Overall, my results suggest that our psychological resources are not confined to the fixed 24-hour clock of time. When there is something we want to do—something that’s important to us—we tap into reserves of energy and focus. It’s like the old adage, “If you want something done, ask a busy person.” Or like the idea of the “runner’s high”: that using up energy can paradoxically give you more. This is consistent with Crosby (1991) who found that people who shoulder multiple roles often feel both overwhelmed and exhilarated.

Subsequent research has expanded on this idea. Indeed, a study by the Center for Creative Leadership’s Marian Ruderman and colleagues (2002) examined the benefits of multiple roles for managerial women and found that the roles women enact in their personal lives provide them with a host of benefits such as social support, practice at multitasking, opportunities to enrich interpersonal skills, and leadership practice that enhance their effectiveness as managers at work.

In an intriguing new study described in a 2014 Council on Contemporary Families research brief, Sarah Damaske, Joshua Smyth, and Matthew Zawadzki of Penn State University measured people’s cortisol levels, one of the key biological markers of stress, and found that people have lower levels of stress at work than they do at home. Moreover, the Penn State team found that while both men and women are less stressed at work than at home, women may get more enrichment from work than men, because unlike men, they reported that they were happier at work than at home.

Of course we all have limits and sometimes run ourselves into the ground. But not as often as one might think given the public discourse. Depletion does exist, but it’s not the only experience we have of how work and family interact. And ironically the film Baby Boom ends with a similar message: Diane Keaton’s character ends up combining her wealth of business knowledge with her experiences as a mom, founding a successful baby food business. Just like the lives most of us lead, it’s ultimately a more complex story, and one that includes enrichment.

References

Andrews, A., and L. Bailyn (1993). Segmentation and synergy: Two models linking work and family. In J. C. Hood (ed.). Men. Work, and Family: 262-275. Newbury Park. CA: Sage.

Crosby, F. (1991). Juggling: The Unexpected Advantages of Balancing Career and Home for Women and Their Families. New York: Free Press.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1987). Sex differences in unipolar depression: Evidence and theory. Psychological Bulletin, 101: 259-282.

Rothbard, N. P. (2001). Enriching or depleting? The dynamics of engagement in work and family roles. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46(4), 655-684.

Ruderman, M. N., Ohlott, P. J., Panzer, K., & King, S. N. (2002). Benefits of multiple roles for managerial women. Academy Of Management Journal, 45(2), 369-386.

About Nancy Rothbard:

Prof. Nancy Rothbard is an award-winning expert in work motivation, teamwork, work-life balance, and leadership. She is the David Pottruck Professor of Management at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. She is also faculty director of Women’s Executive Leadership, a new Wharton Executive Education program running July 14-18, 2014.

Prior to Wharton, Prof. Rothbard was on the faculty of the Kellogg Graduate School of Management, Northwestern University, and holds degrees from Brown University and the University of Michigan. She has published her research in top academic research journals in her field and her work has been discussed in the general media in outlets such as the Wall Street Journal, ABC News, Business Week, CNN. Forbes, National Public Radio, US News & World Report and the Washington Post.