Bias

Most People Agree About Most Things

A periodic reminder that despite stereotypes, we're actually very similar.

Posted January 16, 2023 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- Most people have similar attitudes toward politics and history, but we wrongly perceive large disagreements.

- Scientists call this a perception gap, and is driven by negative stereotypes.

- We should remind ourselves often that most people agree about most things.

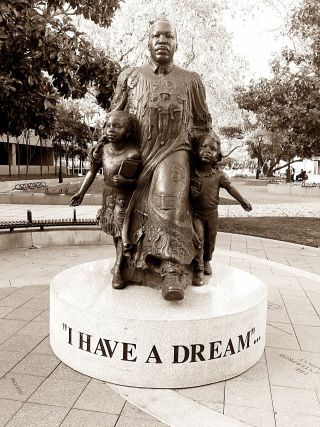

On January 16, 2023, we celebrate Martin Luther King Jr. Day. It’s a national holiday that prompts us to celebrate an important historical figure, recognize historical faults, and reaffirm our aspirations for equality, freedom, and justice. It’s especially important to remind ourselves every year that these are shared values, not specific to any one political group or party.

Research Shows Most People Agree About Most Things

Three years ago this month, I started contributing to Psychology Today. My mission was not only to write about the topics in psychology that I thought were cool and important, but also to see if there are ways to use science to make the world a better place. I started with a simple idea: liberals and conservatives make natural allies in the ongoing struggle against authoritarianism, prejudice, and bigotry.

To support this, I drew from studies by the More in Common research group showing how liberals and conservatives are very similar in their political attitudes and beliefs. But we perceive sizeable differences between these groups (largely due to stereotypes) and underestimate just how much we have in common.

For instance, liberals dramatically underestimate how much conservatives support legal immigration and hold concerns about climate change, while conservatives underestimate how much liberals support police officers and hold concerns about socialism.

Based on the research, it’s clear that liberals and conservatives don’t really belong to different “tribes.” So I adopted this mantra: Most people agree about most things.

Attitudes About Teaching American History in Schools

In a recent study, the same research group published more data on this theme, this time focusing on popular attitudes toward education and American history. They asked a sample of Republicans and Democrats how much they agree with a variety of statements, while asking them to estimate how the other group felt about those ideas.

The researchers found the same pattern as before in their survey data: People held big misconceptions about other political groups that were largely based on stereotypes.

For example, when Democratic voters were asked whether they wanted students to learn about how the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution advanced freedom and equality, 92 percent agreed. But Republicans wrongly estimated that only 45 percent of Democrats would agree. Republicans also mistakenly thought only 42 percent of Democrats would agree that Presidents George Washington and Abraham Lincoln should be admired for their roles in American history, but actually 87 percent of Democrats agreed.

On the other side, Republican voters overwhelmingly agreed (93 percent) that we have a responsibility to learn from our past and fix our mistakes, but Democratic voters wrongly estimated that only 35 percent of Republicans would agree. Democrats also mistakenly thought that only 38 percent of Republicans would agree that Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks should be taught as examples of Americans who fought for equality, but actually 93 percent of Republicans agreed.

Perception Gaps Are Based On Stereotypes

These are huge deficits in how accurate Americans are when thinking about each other. The researchers call these perception gaps. Liberals and conservatives don’t understand each other very well.

Perhaps most importantly, Democratic voters overwhelmingly rejected the notion that students today should feel personally responsible or distressed by American history. This is important because many Republicans have come to believe that Democrats are distorting or weaponizing history lessons in school in order to make certain groups (i.e., White students) feel guilty. But 87 percent of Democrats agreed that students should not be made to feel disempowered or helpless when learning about past injustices, and 83 percent agreed that students should not be made to feel personally responsible for the actions of earlier generations.

On the other side, Republicans overwhelmingly supported the idea that American history has been tainted with atrocities, and that we are better off today because of progress toward equality (especially based on race and gender). Republicans also supported the idea that minorities still face injustices today, and that there is much we can learn by focusing on the histories of specific groups such as Black, Hispanic, and Native Americans.

This is important because many Democrats have come to believe the Republicans are driven by racial resentment, reject the lived experiences of minorities, and are seeking to whitewash American history by ignoring slavery and Jim Crow. None of those ideas are supported by the data. Here’s a great quote from the study authors:

“Many Republicans believe most Democrats want to teach a history defined by shameful oppression and white guilt. Many Democrats believe most Republicans want to focus on the white majority and overlook slavery and racism. But we found that both impressions are wrong.”

Moving Forward With Optimism

It has become normal for people to try to use school curricula and interpretations of American history as parts of a battleground for cultural and political ideas. But we should be careful to remember that we are generally terrible at understanding each other’s beliefs, particularly when we disagree, and we over rely on negative stereotypes about other groups.

I find it ironic to think that while progressives are adamant about eradicating prejudice, they are wrongfully basing some of their beliefs about conservatives on inaccurate, negative stereotypes. And yet despite this, I remain hopeful, as do the More In Common group, that we can move forward in a clearer and more positive direction to achieve our shared goals for society. In the words of the study authors:

“After years of lowering our expectations of each other, this is a moment to imagine something brighter. We can start building this better future together with meaningful conversations about how to teach our past.”

References

Hawkins, S., Vallone, D., Oshinski, P., Xu, C., Small, C., Yudkin, D., Duong, F., Wylie, J. (2022). Defusing the history wars: Finding common ground in teaching America’s national story. More in Common.