Self-Harm

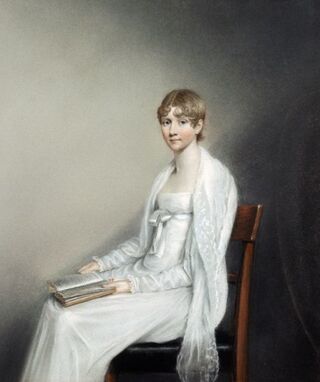

A Portrait of Caroline Darwin

Charles Darwin's sister may have been smarter than he was. Here's why.

Posted March 21, 2022 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- After Charles Darwin lost his mother at the age of 8, his sister helped raise him.

- Charles and Caroline shared a lively correspondence: She was interested in his work and, he said, a good critic.

- In the memoirs he finished at the end of his life, Charles admitted his sister was quicker-witted than he was.

- Caroline's intellect notwithstanding, Darwin concluded that women were the intellectual inferiors of men in 'The Descent of Man.'

Charles Darwin was orphaned by his mother at the age of 8. His father, a successful Shrewsbury doctor, never remarried. But he managed to raise all six of his children.

Charles’s sister Caroline, who was nine years older than he was, helped. As he wrote in his Autobiography at the age of 78: “Before going to school, I was educated by my sister Caroline, but I doubt whether this plan answered.” As the Autobiography begins, Charles remembers sitting in the drawing-room on Caroline’s knee at the age of 3. “Whilst she was cutting an orange for me, a cow ran by the window which made me jump, so that I received a bad cut, of which I bear the scar to this day.” Sometimes he avoided her, and sometimes he made things up. “She was too zealous in trying to improve me.” He stole apples from the orchard and fruit from the kitchen garden. “I believe that I was in many ways a naughty boy.”

In a letter from the University at Edinburgh, sent in the spring of 1826, Charles apologized to his sister: “It makes me feel how very ungrateful I have been to you for all the kindness and trouble you took for me when I was a child.” He went on: “Indeed I often cannot help wondering at my own blind Ungratefulness.” Their correspondence would be kept up all their lives.

Less than a year after he set sail on the Beagle, Caroline sent a letter from Shrewsbury. “I was so glad to get your last letter of November 24th with such a happy account of yourself & I must congrat— you on being so successful and preserving in collecting I shall be very curious to read in your journal how you first heard of the Megatherium Coat.” She reassured him that she would protect his reports: “Your journal is quite safe & we are far from thinking you overcareful in being most anxious I should not be lost.”

He asked her for criticism, and in October, she wrote: “I have been reading with the greatest interest your journal & I found it very entertaining & interesting, your writing at the time gives such reality to your descriptions & brings every little incident before one with force.” She did think he made use of too many flowering French expressions in places, an effect no doubt of reading and liking von Humboldt so much. She preferred her brother’s own simple, straightforward, and agreeable style: “Remember, this criticism only applies to parts of your journal, the greatest part I liked exceedingly & could find no fault, & all of it I had the greatest pleasure in reading.”

Over the years, the letters went back and forth. From London, not long after the Beagle docked, Charles sent reports on how his Journal of Researches was being rewritten for publication. “You being my Governess, I am bound to tell you how my books go on.” She reminded him how enormously proud she was of his work: “You must now hear how your fame is spreading.”

He wrote about the progress he made in his writing on coral islands. And she remained an intelligent critic. In the days after The Origin’s publication, Charles wrote: “I am astounded that you care as much for my Book as you seem to do. Your doubt and queries are perfectly correct. Lyell was bothered on the same point.”

But in one of his last publications, in his 1871 book On the Descent of Man, in a paragraph on the descent of women, he denigrated his zealous and kind governess and perfectly correct sister:

“The chief distinction in the intellectual powers of the two sexes is shewn by man’s attaining to a higher eminence, in whatever he takes up, than can woman—whether requiring deep thought, reason, or imagination, or merely the use of the senses and hands. If two lists were made of the most eminent men and women in poetry, painting, sculpture, music (inclusive both of composition and performance), history, science, and philosophy, with half-a-dozen names under each subject, the two lists would not bear comparison. We may also infer, from the law of the derivation from averages, so well-illustrated by Mr. Galton, in his work on ‘Hereditary Genius,’ that if men are capable of a decided pre-eminence over women in many subjects, the average of mental power in man must be above that of woman.”

Caroline Darwin married her cousin Josiah Wedgewood III, a son of her mother’s brother, in 1837. They had four daughters. Charles married Josiah’s sister, his cousin Emma, in 1839. They had four daughters and six sons. Their lives would be very much the same in many ways. But Charles would compile a great body of work, and Caroline would admire him for it.

She never became a bored medical student in Edinburgh or a beetle-collecting botanist and theology student at Cambridge; nobody asked her to circumnavigate aboard the Beagle as ship’s naturalist or to collect specimens or to publish a journal. Her curiosity was piqued, but she lacked experience. And were it not for her letters to her brother, now available online, nobody should know her name.

In a little over a century, that’s started to change.

References

Darwin, Charles Robert. 1876-. Autobiography, edited by Nora Barlow. London: Collins, 1958.

Darwin, Charles Robert. Correspondance, 1821-1861, edited by Frederick Burkhardt. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985-.

Darwin, Charles Robert. 1871. The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex. London: John Murray.