Empathy

The Unkindness of Strangers

Personal Perspective: I responded to an unkind gesture this way. What about you?

Posted May 8, 2024 Reviewed by Davia Sills

No way was I going to miss this appointment. I’d waited eight months—longer—to get it. The clinic wasn’t accepting new patients until next year, but I kindly called, over and over, until they found something.

I’d been limping since last spring, and no one knew why. I had to stop jogging, and now I couldn’t even walk. People kept asking, “Why are you limping?” I shrugged and quickly changed the subject.

That morning, I’d taken my (limpy) neighborhood walk, showered, and dressed. I planned to arrive early, ensuring traffic—and nothing else—got in my way. In the kitchen I swiped the phone, checking the address so I’d know where to park. But my calendar glared: The appointment was at 9:45—not 10:45, as I’d assumed. It was already 10:00; I was supposed to have checked in 15 minutes ago. The red line on my calendar simply accused me.

“I’m late!” I blurted, slugging green tea and practically spraying it across the kitchen. “Bye!”

Let it be known: I have never been called a “Zen” driver. My driving has been called plenty of other things. I learned to drive in Southern California, where speed is king. I even love driving abroad, where Americans don’t rent cars because driving is “just too crazy.”

I have a zippy little ride and decades of practice going fast, risking yellow lights, and speeding back roads. I used every illegal skill I possessed that morning. I prayed to parking gods, speeding to the building in a record 10 minutes. My prayers were answered: There was a perfect spot right across the street.

Well, not exactly a spot, but that’s the great thing about my tiny car. A not-quite-a-whole-parking-space waited just for me in front of a Jeep. Half the space was a space, and the other half had a yellow line warning the parking ended and the curb began. I’m not a stranger to tickets—a woman at City Parking once said, “Oh, I see you’re a frequent flyer!” I knew this parking job might cost me a $60 ticket (or more if they’d raised fees), but the appointment was worth it.

I pulled in. Perfectly! Silently thanking my dad (who taught me to parallel park), I pulled up, kissing the curb to give the Jeep room to pull out. On the street, I glanced back to see if the Jeep had space to maneuver, hoping so.

I ran in—well, limp-jogged—and made it right up the elevators (another miracle). I rehearsed a plea story if I was too late (I’d worked and gone to school here forever; I’d waited for this appointment forever; I’d been referred by several different specialists; I’m a nurse; all the things). Instead, I said my name, and the receptionist smiled. The clinic was running behind. Another miracle. So grateful.

The limp had gotten worse. Several specialists were stumped but had ruled out a lot of bad initials. It wasn’t ALS, which my mother had. It wasn’t MS (my brain MRI concurred). It wasn’t spinal—my lumbar was a mess of herniations and narrowing, but nothing causing a painless, non-weakening limp.

The spinal surgeon said there was no need for surgery and admitted he didn’t know what was going on. He referred me to physical therapy, sports medicine, general neurology, and so on. I try to avoid unneeded medical visits, but I’d been to primary care, two ALS neurologists, two sports medicine docs, a chiropractor, the spine surgeon, lots of doctors-in-waiting (following their supervisors), and multiple x-ray and MRI techs. They’d thrown up their hands.

I was seeing the general neurologist for this appointment. And bless her, she was running late. I didn’t care how long I sat in that waiting room; I was so relieved to be there.

The physician was so backed up and short-staffed that she came out to call me to a room herself. I’d passed countless neuro exams at this point, but hers was the most complete. She talked. And listened. She “hmm” ed in reassuring ways at the right times; she knew what was up.

Finally, she brought in her attending, a not-very-tall man with a baby-blue shirt and pink bowtie. She made the diagnosis, and he agreed.

“No need to go under the knife!” one of them quipped, referring to the spinal surgeon. “You have dystonia.”

Dystonia, or Runner’s Dystonia, in my case, means involuntary leg contractions caused by dysfunctioning basal ganglia in the brain (they think). For years, I had told providers I couldn’t jog the way I used to. No one paid much attention. Until I couldn’t walk without dragging my leg behind, and I began this obstacle course of clinicians.

The neurologist prescribed medication to minimize the limp, and I start physical therapy next week. Dystonia is rare and often takes up to 10 years to diagnose. I am so fortunate. No ALS. No MS. No Parkinson’s. No scary things. At least for now. Gratefully, I exited the building, practically elated.

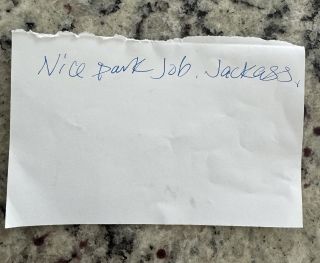

Then I noticed something on my windshield. A ticket. Moving closer I saw it was white, not a canary yellow parking citation. A small white page, torn at the edges. The Jeep was gone, but the owner had left this missive:

“Nice park job. Jackass.”

I hate to admit it, but I stifled a giggle. I had made it to my appointment in time, gotten so lucky with a diagnosis, and didn’t even have a ticket! But I felt so sorry, too. I wanted to apologize to the Jeep owner. I had stressed someone(s) out. I thought of those kitschy quotes about never being mean to strangers because you don’t know what they’re going through.

Would the Jeep driver even care? If they knew why I’d parked that way, would it transform their ire into understanding? Did it matter? They were parked at the Medical Center also. They could be going through something infinitely worse than I was. I wanted to repair my damage, to apologize, but they were gone.

I saved the note. I keep thinking about them. They didn’t deserve my spoiling their hour, their day. Instead of feeling defensive or aggravated—reacting—I had time to pause and give this unknown stranger compassion. What happened to them, I wondered? What made them behave this way? They had every right to their feelings, I knew. My job was to listen, to hear the hurt and frustration beneath, to be kind-hearted to strangers in the world.

And to own that sometimes, without a doubt, I am a jackass, and I'm really sorry.