Psychology

Self-Actualizing the Psychology Internship Experience

How Maslow's theory can transform internship from a job into a Hero's Journey.

Posted November 10, 2022 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- Internship is a critical developmental component of the training path for clinical psychologists.

- Internship should be an important personal and professional growth experience but often feels more like a low-paid clinical job.

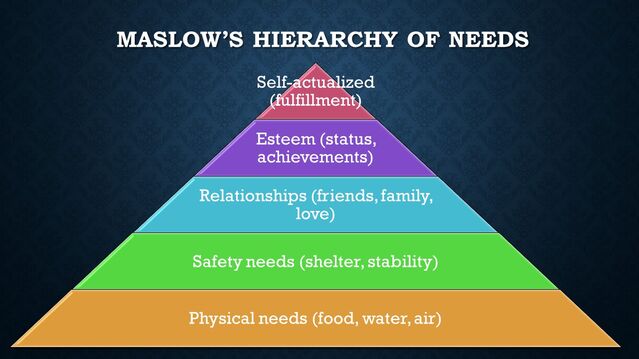

- By adapting growth principles from Maslow's hierarchy of needs, students can better select and shape internship experiences.

For the majority of Americans, November is a harbinger of approaching holidays and seasonal festivities. For thousands of students pursuing doctoral degrees in clinical and counseling psychology, however, November signals the beginning of an entirely different season. For them, 'tis the season of internship applications and interviews.

The Long Training Path

The path to becoming a licensed clinical or counseling psychologist is both long and daunting. For most students, the process will require a decade or more of progressive training. Following four years obtaining an undergraduate degree, students subsequently enter into a competitive process—many programs decline more than 90 percent of applicants—for positions in graduate programs. Once accepted, the subsequent road to a Ph.D. or Psy.D. involves another five or more years of coursework, supervised clinical training, comprehensive exams, a master's thesis, and, finally, a dissertation project. For students surviving this graduate school gauntlet, the completion of a 12-month clinical internship represents the final obstacle to their clinical and counseling doctoral degree.

Interestingly, although internships are required by all clinical and counseling doctoral programs for students to complete their degree and become license-eligible, the internships are not offered directly by the graduate programs. Students must instead enter into yet another nationally competitive process of applying to internship programs at separate institutions. The internship selection process is so competitive that the average student will apply to 15 internship programs to obtain their position.

After the 8- to 10-year journey to reach the stage of internship application, the pressure to obtain a position is understandably intense. Although the American Psychological Association (APA) helps students by accrediting internship programs—a kind of independent quality-control mechanism— the monumental tasks of (1) deciding what programs to apply to and (2) evaluating the internship program contents and supervision components are left almost entirely to the students.

For many students, the application and interview process is stressful, but it works out well. They ultimately receive an internship experience that overall enhances their skills, confidence, and career preparation. For other students, unfortunately, the same internship year can become an obligatory exercise or even a disappointment that does little to advance them as a person or professional. For me—a psychology internship supervisor at a large teaching hospital—the internship year is much too important for students to allow for so much variability. The aim here is to offer students a framework for evaluating internship program contents and help them pursue specific goals that make maximize the quality of their experience.

I consider the psychology internship year to be a voluntary Hero's Journey. If you've read your Joseph Campbell,1 you know that a Hero's Journey is defined by a synergy of adversity, personal growth, and mentorship. This formula certainly describes a good internship program.

Internship is intended to provide a student with 12 months of ongoing challenge, novelty, learning, skill development, career education, and value refinement. Implemented well, the internship functions like a blacksmith's workshop, where the student's ability, personality, and goals are forged into a confident and capable professional through the skillful application of challenging training experiences (adversity) and quality supervision (mentors).

The philosophy behind psychology internship training is highly consistent with the classic Abraham Maslow model of human needs (see figure above2) that theorizes that people are fundamentally motivated to grow toward their highest values. However, I think we can take Maslow's model one step further to offer students tangible training characteristics to seek from their internship programs and supervisors.

Framework for Maximizing Growth and Experiential Quality

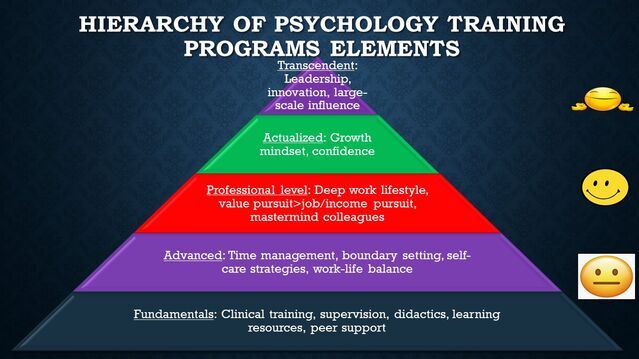

Using the modified Maslow pyramid above to summarize ascending internship "needs," here is a framework I discuss with my own students for maximizing their growth and experiential quality.

- Internship fundamentals. Thankfully, virtually any APA-approved internship will provide the student with exposure to training fundamentals. These include rigorous clinical training, regular didactics for ongoing learning, structured supervision and support mechanisms, and means for the student to integrate their own training goals into the internship to help make the internship a personalized journey.

- Advanced internship training skills. Most accredited internships will also at least introduce students to more advanced skills and growth areas that will be important to them during and after the internship. Beyond their core clinical training, it is critical for interns to view their year as an opportunity to begin developing time management, boundary setting, and work–life balance skills that will be essential to their enjoying a rewarding career as a helping professional.

- Professional-level training skills. In my experience as a supervisor, this is the level where many internship programs fall short of their potential for students. Despite adequate attention to the above areas, intern caseloads, administrative burdens, and performance expectations frequently become overwhelming and isolating. When this occurs, students' learning and growth become secondary to keeping up with clinic demands, and their profound professional needs for depth, connection, and quality (deep work) are sacrificed in the quest for quantity (appointments, handoffs, consults, notes, etc.). A superior philosophy for professionals has been expressed wisely and succinctly by best-selling author Cal Newport: "Do Less. Do Better. Know Why."3

- Actualized-level training skills. At the beginning of each training year, I provide my interns with a collection of carefully chosen professional development books intended to help them improve during their internship in ways both direct and indirect to their clinical roles. At the top of this annual booklist is Carol Dweck's book, Mindset4 for its ability to facilitate an empowering view of a student's potential as a person and professional. Even among the most gifted and hardworking interns, imposter syndrome symptoms run rampant and can corrupt otherwise excellent training years. Sadly, self-doubts among interns can also be impervious to seemingly any amount of positive feedback from patients and supervisors. Left unchecked, a fixed mindset is likely to turn an internship into a painful series of personal judgments for the student and cast a long shadow over their subsequent career.

- Transcendent-level training. The final set of "transcendent" intern skills for which I advocate is the student's ability to see their potential for positive health influence as extending beyond traditional individual and group psychotherapies. Combined with expert didactics and good role models, interns now possess a virtually unlimited capacity for translating their knowledge, values, and communication skills into tools with larger-scale potential for benefit. Such tools include clinical research, smartphone apps, social media, Internet resources, consumer mental health product design, and many others. This skillset, however, requires that students first embrace a professional identity possessing the ethics, talent, and passion to become potential health care leaders, rather than simply health care providers, and expose themselves to novel opportunities for growth in these areas.

References

1. Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1949.

2. Maslow, A.H. (1943) A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychological Review, 50, 370-396.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0054346

3. Newport, Cal (2016). Deep work. London. ISBN 978-0-349-41190-3. OCLC 920740925.

4. Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. New York: Random House.