Aging

Thriving at Old Age: The 3rd-Chapter Problem

How to make old age your greatest adventure.

Posted August 8, 2022 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- Americans 65 and older comprise the fastest-growing age group in our population.

- Adults in the U.S. are not only reaching 65 more often than decades ago, they are also spending more of their life in this age group.

- Unlike youth and young adulthood, there is no preexisting formula or road map for living at older ages. It is up to us to create our own.

At a time when a growing number of Americans are reaching and living well into retirement, it is more important than ever to create a formula for health and happiness in our later years.

Until recently, living long enough to reach the age of retirement was a luxury. For example, in the initial years of the Social Security program in the 1930s, a mere 54 percent of adult men in the U.S. workforce (those age 21 or older) were projected to live to 65—and many of their younger counterparts died before age 21 anyway.

Spring forward to 2022 and these odds have improved remarkably. The same young man or woman now enjoys an 85 to 90 percent chance of enjoying at least some of their retirement years. Globally, the number of people living at ages 65 and older is projected to triple by the mid-21st century, making it by far the fastest growing age demographic. By 2050, more than 1 in 5 people in the U.S. will be age 65 or older.

The so-called "golden years," however, often fail to live up to expectations. Rather than high-quality years liberated from work to enjoy travel, hobbies, and family, this time often instead becomes a period of ageism, isolation, disability, and diminished self-worth. In an American culture that celebrates youth- and middle-age-associated characteristics such as beauty and career status, it is perhaps no surprise that perceptions about old age in the U.S. are negative (1).

Instead of leisure time and grandchildren, those in the pre-65 age group more often associate old age with wrinkles and wheelchairs. With younger-aged adults now highly likely to reach age 65 themselves, and to spend more years in this age group than any previous generation, a better model for living at older ages is sorely needed.

Old Age as a "3rd-Chapter Problem"

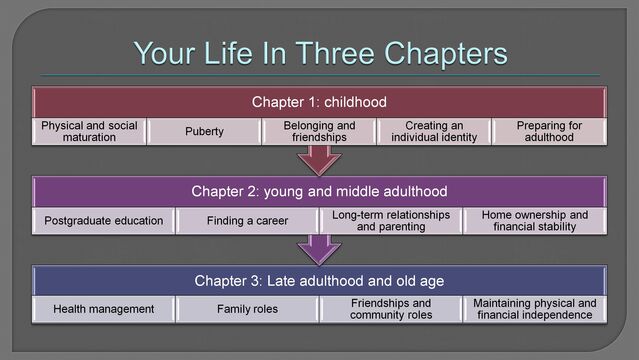

Life in the U.S. can be considered as comprising three chapters: childhood, young- and middle-adulthood, and late adulthood and old age (see Figure 1). These chapters are distinguished both by the challenges characteristic of these periods of our lives and the sources of self-worth, connection, and contribution typically encouraged during these chapters.

Childhood is dominated by challenges associated with physical, emotional, and social development, for instance. Young- and middle-adulthood, by contrast, is typically oriented towards career, family, and financial milestones.

Notice that we usually complete these first two life chapters with the considerable assistance of family, social, and cultural resources. We do not expect a child to navigate the daunting challenges of maturation without parents and educational structure, for example, and we enter adulthood with a cultural roadmap for success—which for many means finding a meaningful career and/or a long-term romantic relationship, raising a family, and achieving economic success or at least stability. Although any given individual navigates this early and mid-life gauntlet in their own way, we each benefit to different degrees from the enormous combination of resources committed in the U.S. to helping children and young adults.

Retirement and old age—Chapter 3 in this model—is the outlier in this story. Relative to childhood and young and middle-aged adults, the retirement-aged person in the U.S. reaches Chapter 3 with no clear formula to follow.

Perhaps because reaching late adulthood and older ages is still a relatively new phenomenon in the U.S., we are still struggling to catch up. Or perhaps because retirement years defy the typically materialistic metrics of adult success, we lack the incentives to develop a model for third-chapter living. For these or other reasons, the adult approaching retirement in the U.S. often encounters an unfamiliar challenge: a life at once unencumbered by young adult expectations yet lacking conventional sources of meaning, connection, and fulfillment.

Given the latter, it is no wonder that many retirement and older-aged adults enter Chapter 3 unprepared and predisposed to struggle. Absent the relationships provided by growing children and co-workers, increased isolation is a common risk. Lacking the sense of growth and purpose that often emerge from career achievements and parenting, life can become devoid of direction and motivation. Finally, health problems associated with older ages frequently steal the opportunities and independence important for thriving in our later years. Any combination of these forces poses a formidable challenge to creating a high-quality life at older ages.

On one hand, we clearly need a societal investment towards developing resources for Chapter 3 living that equal or even exceed those currently in place for younger-aged groups. The demographic forecasts for the coming decades unequivocally show that we'll soon have tens of millions of Americans living into their 70s, 80s, and beyond who will need structures and tools that enable them to remain connected, involved, and valued in broader society.

On the other hand, Chapter 3 is currently the one chapter of life for which we are the primary author. Lacking a cultural formula or societal structure, it can be empowering to realize that the greatest prize of late adulthood is the relative freedom we enjoy in choosing our own values and sources of meaning. Ambiguity can be embraced as a kind of opportunity, the absence of a recipe can become inspiration to explore and create, and the lack of a pre-drawn map can be seen as a well-earned chance to walk our own path.

It is likewise impossible to overstate the importance of appreciating that we are each penning our personal Chapter 3s long before we reach the traditional age of retirement. Young and middle-adulthoods, for example, characterized by poor health habits, are likely to condemn our Chapter 3 to disease and disability no matter our intentions or the availability of external resources. Whether you are now 15 or 55, there is good news: you are overwhelmingly likely to see your retirement years. Will you be ready to enjoy them?

References

1. Growing Old in America: Expectations vs. Reality | Pew Research Center.