Diet

How to Get the Most From Weight-Loss Medications

Even medicines like Ozempic require behavior changes to optimize results.

Posted August 22, 2022 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Key points

- Ozempic and other GLP-1 agonists have radically altered the weight loss landscape.

- Lost among the positive headlines is the sobering fact that Ozempic often leads to large amounts of lean tissue loss.

- With Ozempic, or any weight-loss treatment, exercise, nutrition, and sleep changes are necessary to preserve lean tissue.

Treatment options for weight loss have arguably never looked better. In just the past year, a new class of repurposed diabetes medicines called GLP-1 agonists (GLP=glucagon-like peptide; glucagon is a hormone your body produces to regulate blood glucose levels) have transformed the landscape. For context's sake, consider that prior to these new GLP-1 agonists, even the most effective FDA-approved medicines helped people lose, on average, ~5% of their body weight (i.e., a 15-pound weight loss for a person weighing 300 pounds). As reported in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine in 2021, however, a new GLP-1 agonist called Semaglutide — more commonly known by the brand name Ozempic — produced an average 14.9% body-weight reduction in a randomized controlled trial (i.e., a 45-pound weight loss for the same 300-pound person (1). And with a modified GLP-1 called Tirzepatide looking perhaps even more promising as a weight-loss agent than Ozempic in early trials (2), there is understandably an unparalleled level of excitement about the possibility of finally having safe and highly effective medicines available for the tens of millions of Americans struggling with weight and weight-related health conditions.

Lost in the current hype over Ozempic and other GLP-1 agonist weight loss medicines, unfortunately, is an alarmingly consistent finding: Much of the "weight loss" resulting from GLP-1 agonists is the loss of muscle, bone mass, and other lean tissue rather than body fat (3). For example, in a 2021 trial entitled "Impact of Semaglutide on Body Composition in Adults With Overweight or Obesity" that included pre-and-post-treatment DEXA scans (DEXA is a medical imaging test used to assess body composition and bone density; it is one of the most accurate methods for identifying how much body fat a person has versus "fat-free mass" such as muscle and bone mass), 34.8% of the total weight loss experienced by participants receiving Semaglutide resulted from muscle, bone, and connective tissue (4). Similarly, in a 2020 clinical trial entitled "Effects of once-weekly semaglutide vs once-daily canagliflozin on body composition in type 2 diabetes: a substudy of the SUSTAIN 8 randomised controlled clinical trial," 40% of the seemingly impressive weight loss in the Semaglutide treatment resulted from the loss of lean tissue (5).

Compare these exorbitantly high rates of lean tissue loss with Semaglutide/Ozempic to rates of lean tissue experienced by properly training and dieting athletes. Keep in mind that when an athlete is losing weight for a competition, their goal is to lose 0.0% lean mass (i.e., the goal is to lose 100% body fat). For example, in a 2011 trial comparing two programs for weight loss in a population of experienced athletes, the "slow reduction" group lost 5.6% of their total body weight — with 100% of the loss coming from body fat — while simultaneously gaining 2.1% lean mass (6)! If 35-40% of total weight loss came from lean tissue, such as observed in many recent GLP-1 agonist trials, it would be disastrous for an athlete's strength, endurance, and performance levels.

Although the typical American may or may not have athletic aspirations, the loss of substantial amounts of lean tissue while dieting or using GLP-1 agonists should be no less concerning to them. A significant loss of bone mass, for example, predisposes serious bone diseases such as osteopenia and osteoporosis. And a significant loss of muscle mass lowers metabolic rate (increasing the risk of weight regain), raises the risk of falls, and impairs function and quality of life. With high rates of the U.S. population already suffering from osteoporosis (more than 10 million Americans already and rising rapidly over the past decade) and even more already experiencing metabolic dysfunction (almost 9 in 10 American adults), weight-loss methods increasing the risk of these conditions should be approached with caution.

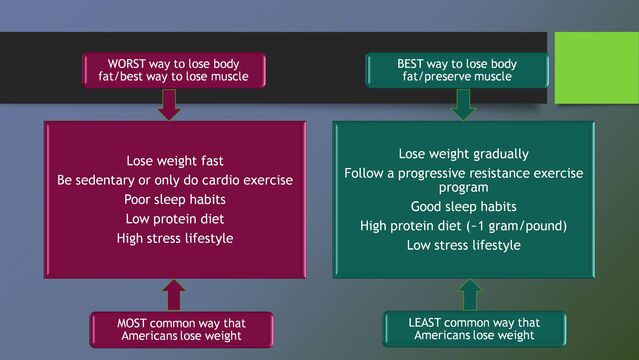

Thankfully, there is a proven and practical approach for using GLP-1 agonists for weight loss while preserving health and function. What is required, however, is the inclusion of specific behavioral and nutrition practices that differ markedly from the conventional way that Americans practice weight loss. As mentioned above, populations such as athletes who are intent on losing only body fat while dieting utilize specific behavioral strategies that are highly effective for preserving muscle and bone mass. These methods are shown on the right side of the above figure and are diametrically opposed to methods used by most people pursuing weight loss.

In relative order of importance, these methods are:

- Aim for slower and sustainable rates of weight loss over time. One of the cardinal rules of dieting is that faster weight loss results in a greater loss of lean tissue. Even in the above-mentioned study of dieting athletes (6), for example, the "fast reduction" group lost a small amount of lean mass despite rigorous weight training (whereas the "slow reduction" group actually gained lean mass).

- Combine dieting or weight loss with progressive resistance training — e.g., engaging in 2-3 weekly sessions of weight training or body weight calisthenic exercises, using a level of resistance that allows one to perform 5-12 repetitions before muscular failure and attempting to progress in resistance or repetitions at the same level of resistance over time (7).

- Prioritize a regular and high-quality sleep schedule (8). Recent clinical trial evidence makes clear that dieting under conditions of poor sleep results in a dramatically higher percentage of the weight loss coming from lean tissue instead of the desired body fat.

- Maintain or even increase protein intake. When reducing calories, research indicates that protein should be preserved, with reductions instead coming from fat and carbohydrate intake (7). Although absolute rates vary across studies, exercise reviews suggest that consuming approximately 1 gram of protein per pound of body weight (i.e., 200 grams of protein for a 200-pound person on a diet) is optimal for maintaining lean tissue under conditions of calorie reduction.

- Reduce sources of chronic stress as much as possible when losing weight and/or practice stress reduction strategies. Conditions of chronic stress produce important changes in anabolic (e.g., testosterone) versus catabolic (e.g., cortisol) hormone profiles in our body. Chronically elevated rates of these catabolic hormones increase the breakdown of muscle and bone mass for energy and this effect can be magnified when also reducing calorie intake.

Summary

As a health psychologist, my goal is to help people lose weight in ways that enhance their health, function, and quality of life. While excited about the promise of GLP-1 agonists such as Ozempic, I am also concerned that the rapid and substantial weight loss people are otherwise enjoying will obscure the hazards of significant lean tissue loss and distract them from the need to combine their GLP-1 program with the behavior strategies necessary for preserving muscle and bone mass.

References

1. N Engl J Med 2021; 384:989-1002. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2032183

2. N Engl J Med 2022; 387:205-216. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2206038

3. Ida S, Kaneko R, Imataka K, Okubo K, Shirakura Y, Azuma K, Fujiwara R, Murata K. Effects of Antidiabetic Drugs on Muscle Mass in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2021;17(3):293-303. doi: 10.2174/1573399816666200705210006. PMID: 32628589.

4. Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Calanna S, Van Gaal LF, McGowan BM, Rosenstock J, Tran MTD, Wharton S, Yokote K, Zeuthen N, Kushner RF. Impact of Semaglutide on Body Composition in Adults With Overweight or Obesity: Exploratory Analysis of the STEP 1 Study. J Endocr Soc. 2021 May 3;5(Suppl 1):A16–7. doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvab048.030. PMCID: PMC8089287.

5. McCrimmon RJ, Catarig AM, Frias JP, Lausvig NL, le Roux CW, Thielke D, Lingvay I. Effects of once-weekly semaglutide vs once-daily canagliflozin on body composition in type 2 diabetes: a substudy of the SUSTAIN 8 randomised controlled clinical trial. Diabetologia. 2020 Mar;63(3):473-485. doi: 10.1007/s00125-019-05065-8. Epub 2020 Jan 2. PMID: 31897524; PMCID: PMC6997246.

6. Garthe I, Raastad T, Refsnes PE, Koivisto A, Sundgot-Borgen J. Effect of two different weight-loss rates on body composition and strength and power-related performance in elite athletes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2011 Apr;21(2):97-104. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.21.2.97.

7. Edda Cava, Nai Chien Yeat, Bettina Mittendorfer, Preserving Healthy Muscle during Weight Loss, Advances in Nutrition, Volume 8, Issue 3, May 2017, Pages 511–519, https://doi.org/10.3945/an.116.014506

8. Nedeltcheva AV et al. Insufficient sleep undermines dietary efforts to reduce adiposity. Ann Intern Med. 2010 Oct 5;153(7):435-41.