Media

Human or Psychologist?

One way to help students think critically and self-reflect at the same time.

Posted June 29, 2017

Critical thinking, at it's base, begins with the ability to evaluate claims by evaluating the evidence that supports (or refutes) those claims. For example, when a politician or pundit claims that a particular political ad “was very effective,” some of the basic questions that critical thinkers might ask would be, “How does the author know that? Does the author base the conclusion on his or her own reaction to the ad? (If so, the statement is an opinion, not a fact.) Did the author do an empirical study to gather evidence? If so, what kind of study was it? A survey? An experiment? How did the researchers (if any) measure ‘effectiveness?’ A questionnaire about viewers’ opinions? Voting behavior? Campaign contributions?” You get the idea.

It’s great fun to discuss articles, descriptions of psychological research, and other material in class and talk about such important things as the motives of the authors, the presence and adequacy of evidence, how psychologists might design empirical studies to test the claims made, and the source of the article itself. I have discussed elsewhere my assignment of POT papers (“Proof of Thinking”) in which students critically analyze an article, something I said in class, or other material.

As I read these POT papers, I was impressed at students’ developing skills in exploring someone else’s statements. What I noticed, however, was that students were making their own mistakes. They would say something like, “This article is not based on any credible evidence.” This statement may or may not be true, but the student is not in the position to judge ALL the evidence! A more careful statement (one that a psychologist or other scientist might use) might be: “This article did not make clear whether any empirical research had been done to substantiate the claims made.”

I have been exploring ways to help students think more critically about what they see and hear in the media, and to recognize flaws in their critical thinking about their own writing. This is why I designed the “Human or Psychologist?” exercise.

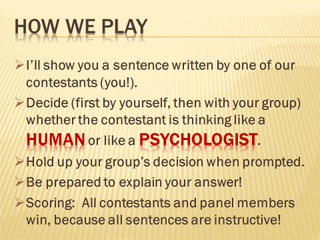

The format is a quiz show in which I present a series of statements and students decide—individually and then in groups—if each statements shows good critical thinking (Psychologist) or not-so-good (Human). If the statement is Human, students suggest ways to turn it into a Psychologist statement.

Here’s the kicker: The statements I use are from the students’ own POT papers! I don’t identify any of the authors, of course, but the exercise seems to be engaging because students are considering their own work. Indeed, several students have said to the class, “I wrote that statement, and here’s how I would improve it….”

Here are a few examples of POT paper statements we’ve considered in “Human or Psycholgist?”:

“In today’s world, most people due to their egos do not admit or acknowledge mistakes often.” Human. Students noted that the author did not have any data to support a statement about “most people,” let alone to support a reason that people may not admit mistakes.

“Should her point be true, it does mean that an alternate treatment for depression may be a good thing to look into.” Psychologist. Students noted that the author didn’t take the article’s point to be true, but did explore some possibilities. The author was also approporiately tentative by saying “may be” rather than “definitely is.”

“The author was able to accurately describe this experiment due to her ten year experience working with Medical News Today.” This was in between! The Psychologist part was looking for evidence for the accuracy of a description. That was good. The Human part was assuming that years of experience is definitive proof of accuracy of a given description rather than one possible bit of evidence. (Both Humans and Psychologists use split infinitives, so that didn’t count in either direction…)

My students learn a lot by reflecting on their own thinking in addition to aiming their analysis at others. Of course, my previous sentence is Human, because I have no empirical data to support my opinion!

----------------------------------------------------------------

Mitch Handelsman is professor of psychology at the University of Colorado Denver. With Samuel Knapp and Michael Gottlieb, he is the co-author of Ethical Dilemmas in Psychotherapy: Positive Approaches to Decision Making (American Psychological Association, 2015). Mitch is also the co-author (with Sharon Anderson) of Ethics for Psychotherapists and Counselors: A Proactive Approach (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010), and an associate editor of the two-volume APA Handbook of Ethics in Psychology (American Psychological Association, 2012). But here’s what he’s most proud of: He collaborated with pioneering musician Charlie Burrell on Burrell’s autobiography.

© 2017 by Mitchell M. Handelsman. All Rights Reserved