Intelligence

Beware of the Rectangles

The illusions of our screens make us prisoners in a two-dimensional world.

Updated April 25, 2024 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Length, width and height: within these three dimensions reside the countless objects of our world, each revealing an important aspect of reality. However, if we're forced to examine these same objects in two dimensions, like the prisoners in Plato’s cave, we're taken hostage in a realm of illusions. In Plato’s famous allegory, prisoners in a cave are chained to a wall, prohibited from seeing the actual three-dimensional (3D) objects passing through their cave: instead, they see only two-dimensional (2D) shadows of those 3D objects. As a result of this punishment, Plato's prisoners develop numerous misperceptions about the world and existence.

Though we are taught Plato's cave allegory as a cautionary tale, warning us about the dangers of ignorance, over the past century we have made ourselves voluntary prisoners, allowing ourselves to be misled by the 2D images on each of our rectangles: our digital screens. For us, as with Plato's prisoners, the 3D world has been flattened to fit into two dimensions.

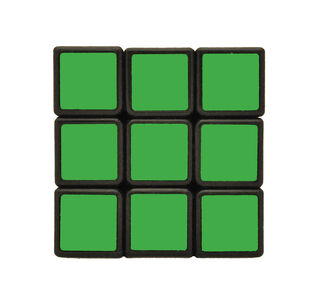

What are we losing in this great flattening? Consider the Rubik’s Cube.

Like all cubes, a Rubik’s Cube has six sides; and when solved it displays a different color on each side. In looking at the picture of the Rubik’s Cube shown here, which displays just one of the cube's six sides, you can only know for sure the color of the side that is shown in the picture (in this case, green).

If I were to suggest anything about one of the other sides of the cube—e.g., that it was red—there would be no way for you to know if I was telling the truth: you would either need to take my word for it or concede that it was impossible for you to know the color of that side.

However, if instead of showing you a 2D picture I gave you an actual Rubik’s Cube to hold, you would have the opportunity to examine it completely and see for yourself what colors were on each of its six sides and determine whether I spoke the truth or was lying.

Virtually every child who has achieved object permanence understands that when we flatten 3D objects into 2D spaces we lose valuable information. Unfortunately, this is something that we adults continue to forget.

Over the past century, our lives have become increasingly dependent on digital rectangles: TVs, computers, smartphones, etc. To be sure, these rectangles hold great power and potential. But we seem to forget that every experience we have on our rectangles has been carefully curated for our consumption. In the same way that we crop our photos on Instagram to remove any unflattering body parts (for me, it’s my spare tire), those who provide the content we consume on our rectangles edit their content so that we are most likely to perceive it in the way they intend.

In the free market media landscape we inhabit, content providers are eager to fill our rectangles with sensationalized content—i.e., entertainment and stories that are shocking and emotional—precisely because it presents a stimulating distortion of reality, which is why it is so profitable. We don't watch TV to see the boring details of our everyday lives on screen, we watch TV for the sensationalized excitement that our everyday lives lack. When sensationalism is the goal, the most extreme events get disproportionate attention and usually in a way that exaggerates their most controversial features, with details getting cropped out that would have provided important context.

In journalism, there are several aphorisms that reflect the culture of sensationalism within the industry, such as: "If it bleeds, it leads"; "A man bites dog story is more interesting than a dog bites man story"; and "You never read about a plane that did not crash." The more we're exposed to sensationalism on our 2D rectangles, the more likely we are to believe that low-probability events are much more common than they actually are.

Sensationalism biases have the capacity to affect our mood and significantly alter our behavior. When we believe that plane crashes occur more frequently than they actually do, the increased anxiety leads many people to avoid flying and miss out on many life-changing experiences. Similarly, when we believe that the world is more violent now than it ever was—a perspective that Steven Pinker has tried to rebut with his research in The Better Angels of Our Nature—it makes us all more cynical, more abrasive, and less trusting.

As a psychologist, one of my duties is to help people examine the validity of their beliefs and provide added perspective so they can make the healthiest decisions possible. In our world, determinations of what is safe and what is dangerous, or who is a heroine and who is a villain, are dependent on which side of the cube you are shown. Thankfully (tongue firmly in cheek), we have our favorite cable news outlets—on the left and the right—broadcasting only the side of the cube their viewers most want to see, at the exclusion of all other sides.

Is it any wonder then that a recent AP-NORC/USA poll found that nearly half of those surveyed admitted that they “struggle to know if the information they consume is true”; and about 60 percent say they “consistently see clashing reports from different outlets about the same set of facts?” The problem isn't limited to journalism, either. In a New York Times op-ed, microbiologist Dr. Elisabeth Bik highlights the ways scientists have increasingly used digital editing to alter images of their work to make claims that are not supported by their data.

In light of the distortions of our rectangles, I offer a few antidotes to those who aspire to psychological well-being. First, try to limit your "rectangle" exposure to only that which is essential. By their very nature, our rectangles flatten the world into 2D projections, forcing us into the role of spectator, where it’s impossible to have a dialogue with content providers to get clarifying context about things presented to us.

Second, for whatever content you do consume on your rectangles, suspend your judgment until you get additional layers of confirmation from your direct, personal experiences. Remember that all of the content we receive on our rectangles has been curated with the goals of sensationalism and stoking emotion. Therefore, ask yourself what details may have been cropped out of each story or picture you see (including this very article), and never stop asking yourself: “How do I know this is actually true?”

Finally, consider spending more time in 3D relationships with the humans in your life. Though not all of the information you get from people in the real world will be true, these interactions will at least help you acquire the context necessary for making the most informed decisions possible.

In the end, we may never get to see all sides of life’s cube, but stepping outside of Plato’s cave more often will help us to better understand our world in all of its three-dimensional complexity.

References

American Psychological Association (2018). APA Dictionary of Psychology (online): https://dictionary.apa.org/object-permanence

Pinker, S. (2015). The Better Angels of Our Nature. New York, NY: Penguin Group USA.

Plato. Grube, G.M.A. (trans.); Reeve, C.D.C (ed.) (1992). Republic Book VII. Cambridge, MA: Hacket Publishing Company Inc. pp. 186–212.

Riccardi, N. & Fingerhut, H. (2019). AP-NORC/USAFacts poll: Americans struggle to ID true facts. Associated Press (online): https://apnews.com/c762f01370ee4bbe8bbd20f5ddf2adbe