Resilience

Failing Your Way to Success

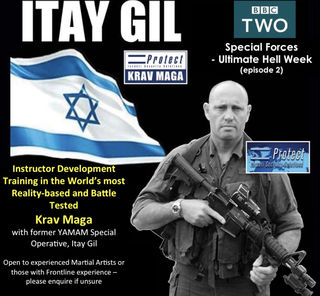

Stress to resilience: A guest post by Israell counterterror expert Dr. Itay Gil.

Posted March 9, 2020 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

The following article is guest written by Dr. Itay Gil. Dr. Gil was co-author of my previous article on Resilience – The Ultimate Stress Test. That article focused on how highly resilient recruits were selected for service in the elite Israeli special forces counter-terror warfare unit called Yamam.

Dr. Gil was one such combat member and instructor. He has dedicated his life to studying and teaching principles of security and resilience. This article deals with some of the resilience training methodologies that the Israelis (under Dr. Gil) have utilized in the Yamam, to foster resilience in high-level counter-terror operatives.

As a former operator with 14 years of experience in the Israeli special forces with a focus on counterterrorism and more than 20 years as a captain in the reserve special forces, I have observed the phenomenon of human resilience through hundreds of severely high-risk operations.

The word “resilience” conveys a powerful concept of a transcendent characteristic or capability in people who can persevere through stress. It enables a person to adapt to multiple challenges and levels of stress to achieve goals, whether it is their career, relationships or business. Stress could mean anything from being called a bad name to the death of a significant other. For an Israeli special forces fighter, resilience means being able to endure in situations of extreme danger where the outcome is unpredictable and easily lethal.

In this light, it is discouraging to see many young people benchmark their success in life through heavy involvement with social media: Not achieving enough followers and likes means that they’re not succeeding, causing them to experience negative emotions. They have allowed something beyond their control to become the hinge for their internal state, increasing the risk for anxiety and mood disorders (Keles, McCrae and Grealish, 2020).

This is concerning since we as a society should prioritize internal strength over external influences. Resilience is a very real parameter that can be developed and up-regulated to enable a person to internally maintain a steady state of operation and pursuit despite setbacks and negative perceptions from others.

Here are four strategies we've adapted to foster resilience in elite counter-terror warfare soldiers.

1. Process Visualization

Developing a clear awareness of one’s goals, their attendant requirements, and their array of possible outcomes. We must know what we need to accomplish, the skills required to do so, and a reasonably-estimated likelihood of success and failure.

We ask our special-forces trainees to visualize the mission with its foreseeable risks, take an internal inventory of their skills, estimate what could be the worst and best outcomes, and determine their reactions to each. This includes imagining the worst, catastrophic mission consequences resulting in their complete physical and emotional breakdown including capture and torture. They also visualize mission success, associated with the capture or neutralization of the terrorist with the absence of causalities.

Between these extremes, the trainees rate on a Likert scale the progression of best to worst outcomes and their subsequent reactions. In doing so, each trainee develops for themselves an individual “barometer” linking perceived mission outcomes and their predicted associated stress reactions.

This predictive clarification exercise confers a protective effect. The process of outlining an internal map and agreement on how they would react to a range of possibilities primes cortical-amygdala neuro-circuitry to process fearful stimuli so as to lower activity in the amygdala (Ochsner and Gross, 2005).

In pre-deployment training, visualizing both combat and their own reactions entrains them to predict and reflect on their response to stressful events. The result: a fluidic and automatic processing of subsequent and actual reactions in the field and reduction of hyper-arousal — a known antecedent for acute stress reactions and post-traumatic stress disorder.

2. Goal-setting

The next pillar of resilience development is goal setting, which is well-known in sports psychology. Our trainees are directed to form specific goals in regard to their own stress-reaction scale. We pose to them the question: “Would you be able to downgrade your subjective response to its corresponding outcome?”

Based on their specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bounded (SMART) goals, the trainees are then subjected to the hallmark of Israeli special-forces training, which is the third pillar of resilience development.

3. Repetitive Training to Failure

Special forces training in Israel incorporates repetitive training to failure. We utilize immersive and intensive high-fidelity exercises simulating actual combat conditions to such a degree that the trainees are almost traumatized from the frequent mission-simulation failures.

Tools, predominantly the lack of intelligence about mission-simulation details, and secondarily non-lethal rounds and explosions, live-tissue training, covert hostiles, team-member(s) degradation, time pressure, and mass simulated-casualties are employed to shock their expectations and test their coping skills. This is based on the principle of productive failure — errors generated from engagement prior to instruction in conjunction with opportunities to consolidate and reflect, produce better learning outcomes (Kapur, 2016).

4. Debriefing

Debriefing sessions include corrective instructions on strategy, tactics, and cognitive-behavioral training for stress response management, allowing the trainees to absorb and generalize the content in a much better way than if they knew what to expect in the preceding simulation(s).

We also observe from the hundreds of accumulated simulations that most trainees also reduce stress-reactions to their predicted worst-case scenarios. Whether the improvement is primarily due to the repetitive exposures or to the awareness of their reactions in Debriefing created by their stress-reaction calibration and goal-setting is not known.

Civilians

How may this be applicable to civilians in high-performance occupations? For the athlete like a mixed-martial-arts competitor or professional tennis player, he/she may want to pre-visualize and set out their stress-reaction scale so as to reduce the chances of faltering under pressure. In other words, they may want to undergo failure or near-failure simulations with their scale in mind so they do not decompensate due to panic. For the police officer, who can be exposed to life-endangering scenarios, he/she would benefit from undergoing high-fidelity use-of-force drills along with the understanding and self-acknowledgment of his/her stress reactions. Then with progressively harder and more intensive scenarios, the officer would slowly up-regulate his/her ability to manage his or her level of arousal.

What About PTSD?

Conventional approaches to PTSD prevention and treatment for the military have not been hugely successful. Kemplin, Paun, Godbee and Brandon (2019) argue that the over-emphasis on positive psychology (positive thinking, virtuousness, optimal living) in resilience development in the military is a misaim and does not properly address the individual pain and suffering of chronic stress reactions. This approach also isolates those suffering and labels them as being pessimistic, less virtuous and not living one’s best life.

In a recent article in the Journal of American Medical Association, Steencamp, Litz and Marmar (2020) did a survey of the efficacies of first-line psychotherapies for military-related PTSD and found that only 33-50% patients significantly benefitted from the VA and DOD clinical practice recommendations of trauma-focused psychotherapy (Prolonged Exposure and Cognitive Processing Therapy). Perhaps the issue is that one-size-doesn’t fit all. Individualistic training directed to the severe difficulties and disappointments of military theatre operations and the person’s own reactions to such, similar to the strategies delineated above may be of some benefit.

Fostering Resilience in Children

How we raise our children greatly influences their ability to manage challenges. While approximately half of the variation in resilience-related traits, such as mental toughness, are accounted for by genetic factors (Vukasovic and Bratko, 2015), exposure to manageable, nontraumatic stressful events during childhood may heighten resilience (Horn and Feder, 2019). Crust and Clough (2011) described three factors that contribute to mental toughness in children: 1) providing a challenging yet supportive environment; 2) having an effective social support mechanism; and 3) encouraging reflection which emphasizes the value of experiential learning. It appears that raising resilient children involves a less permissive parenting style, chores for which the child is held accountable, lots of challenging team and individual sports that promote learning from failure, coupled with close friendships and many opportunities to openly discuss problems and solutions. These strategies may enhance their ability to exercise emotional and cognitive control, remain committed to goals, seek challenges and are confident in their ability to overcome setbacks and failure.

Thanks for tuning in. As always, opinions and comments appreciated.

References

Betul Keles, Niall McCrae & Annmarie Grealish (2020) A systematic review: the influence of social media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in adolescents, International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 25:1, 79-93, DOI: 10.1080/02673843.2019.1590851

Crust, L and Clough, PJ (2011) Developing mental toughness: From research to practice, Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 2, pp 21–32

Kapur, M. (2016). Examining Productive Failure, Productive Success, Unproductive Failure, and Unproductive Success in Learning.

Kemplin, K.R., Paun, O., Godbee, D.C., & Brandon, J.W. (2019). Resilience and Suicide in Special Operations Forces: State of the Science via Integrative Review. Journal of special operations medicine : a peer reviewed journal for SOF medical professionals, 19 2, 57-66 .

Horn, S.R., & Feder, A. (2018). Understanding Resilience and Preventing and Treating PTSD. Harvard review of psychiatry, 26 3, 158-174

Ochsner, K.N., & Gross, J.J. (2005). The cognitive control of emotion. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9, 242-249.

Steenkamp MM, Litz BT, Marmar CR. (2020). First-line Psychotherapies for Military-Related PTSD. JAMA. Published online January 30, 2020. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.20825

Vukasovic ́, T., and Bratko, D. (2015). Heritability of personality: a meta-analysis of behavior genetic studies. Psychol. Bull. 141:769. doi: 10.1037/bul0000017