Media

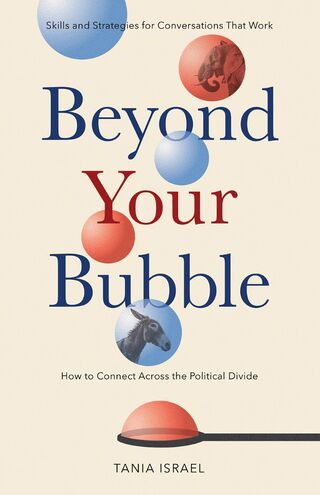

Beyond your bubble

The Book Brigade Talks to Psychologist Tania Israel

Posted September 10, 2020 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

In a world full of talk, much of it is angry, self-serving, and unheard. Real conversation is something else entirely, and it takes the right motivation and the right skills.

Your book, Beyond Your Bubble, is about conversation. How deeply does the failure of conversation today affect us?

Not being able to engage in conversation, whether it’s an actual failed attempt or simply avoidance of talking with people who hold disparate views, is driving a wedge into our relationships with family members, friends, and co-workers. People are avoiding talking about politics or avoiding people with whom they imagine there would be political conflict, and the real or imagined conflict is causing distress. It’s not surprising that a study conducted by the American Psychological Association found that people in the U.S. are experiencing increased stress due to political conflict.

How did we get into this state?

Media tends to portray conversation across political lines as debate and diatribe between extremist spokespeople who are invested in expressing their views rather than understanding different perspectives. Clearly, this does not provide role models for a productive conversation. Social media contributes, as well. The interactions we have with people on Facebook and Twitter are not real conversations.

In real conversations, we can express and perceive nuance in tone and nonverbals. We might have a different kind of conversation with someone who agrees with us than we would have with someone who disagrees with us; this kind of flexibility is healthy, but it cannot be achieved on social media. Conversation can help us to deepen our understanding of our own views, as well as someone else’s. Social media creates the illusion of conversation, but the expression is so limited that it reinforces stereotypes of people with different views and solidifies our echo chambers of agreement.

What is the secret of connecting with people who have different views?

There are a few key motivations I hear from people who want to connect across the political divide: They want to maintain an important relationship in their lives, persuade others, seek common ground, or they’re simply feeling distressed or having difficulty understanding why people think or act as they do. In order to achieve any of these goals, there are only two things you need to do: Try to understand the other person and help them feel safe and understood. There are a few key skills that will help people do these things: Listen, manage emotions, gain insight into their perspective, and share your own views effectively.

Why do people feel pessimistic about bridging the political divide?

As humans, we tend to pay attention to information that supports our perspective while viewing ourselves as forming opinions based on evidence and morality, which we contrast with those of other people. These predispositions contribute to distorted perceptions of people who are on “the other side” as uninformed, illogical, uncaring, and extreme in their views. Combined with media representations and social media interactions, our minds are unlikely to conjure images of successful dialogue.

What do you do that gets people over their pessimism?

I teach people skills that will help them engage in productive dialogue. I don’t mean that I just talk about the value of these skills—I actually help people develop and practice them. This builds confidence that they can implement the skills for productive dialogue. I also help people understand and correct their distorted perceptions of people whose views, values, and experiences are different from their own.

Is the failure of dialogue really only a matter of lack of skills? Or is it something deeper?

Skills are key, but someone will implement the skills only if they are motivated to do so and have some confidence in the potential for a successful outcome. As I mentioned, there are some common motivations, but sometimes people hold conflicting motivations. For example, perhaps you want to maintain a relationship, but you also want to express yourself and feel validated. Both of those are reasonable motivations, but it might not be productive to try to get them all met in a single conversation. Maybe you can seek out someone who agrees with you in order to meet your needs for expression and validation, so it doesn’t interfere with your attempts to maintain a relationship with someone who has a different view.

Confidence in a successful outcome requires awareness of motivations, as well as accurate perceptions of dialogue partners, achievable models of dialogue, and success in implementing skills. I’ve already talked about motivations and correcting distortions. Regarding modeling, the book provides examples of dialogue between fictional cousins who discuss topics such as health care, gender identity, Black Lives Matter, and abortion. They can help the reader get a picture of what successful dialogue can look like. I also recommend practicing skills in low-stakes situations in order to hone the skills and develop self-efficacy.

If you had to cite one skill that is most lacking, what one is it?

The most potent skill that’s often missing is active listening, or what Steven Covey calls “listening to understand” rather than listening to respond. Active listening consists of offering space for someone to speak, reflecting back a summary of what they’ve said, and asking questions that are open-ended rather than those that can be answered with a “yes” or a “no.”

How does one even get a person of an opposing viewpoint to the table for a discussion?

You invite them. If you’re having trouble finding the words, I provide some scripts in the book. So often, though, we don’t even ask, and we assume others would not want to engage in conversation with us. Of course, they’re not going to want to connect if they feel that you’ll just berate them for their views, so you need to feel and communicate your openness to dialogue.

What is the most important thing to do or say in launching a dialogue?

The most important frame of mind is intellectual humility, which I think of as being righteous without being self-righteous. In other words, you can hold strong opinions while being curious about and respectful of other views. Something you might say that reflects intellectual humility is, “I really want to understand more about where you’re coming from,” and then you actually need to listen!

Are there important things to avoid in developing a dialogue?

Sure, but I like to think of them as “things to do instead of” rather than “things to avoid.” For example, after someone shares their view, instead of responding with your own contrasting opinion, try summarizing what they said. Also, instead of sharing statistics and slogans, try talking about your journey that led to your stance on an issue. Or, after someone identifies their position on a policy, rather than telling them they are racist, uninformed, or will sink the economy, try asking them to elaborate on what implementation of that policy would look like.

What are the most common mistakes people make in political dialogue?

The single most common mistake people make is thinking that saying something that they think will change someone’s mind—a fact, an opinion, even a feeling—is more important than trying to understand the other person. A second mistake, and one that often prevents dialogue altogether, is believing the cognitive distortions we hold about people whose views differ from our own.

What is the single most important message of your book?

Hope. I want readers to feel confident and optimistic that dialogue across political lines is possible, and I want them to have the skills and resources to achieve their goals.

About THE AUTHOR SPEAKS: Selected authors, in their own words, reveal the story behind the story. Authors are featured thanks to promotional placement by their publishing houses.

To purchase this book visit: Beyond Your Bubble