Fear

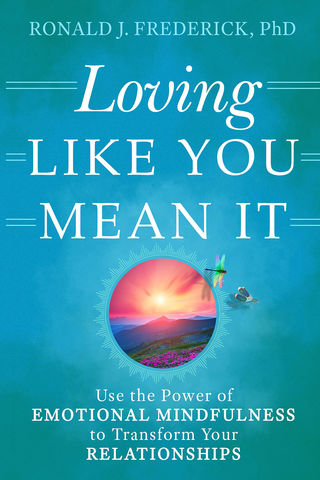

Loving Like You Mean It

The Book Brigade talks to psychologist Ronald Frederick.

Posted March 28, 2019

There are many ways people get stuck in bad relationship patterns. But the most basic of all may be relating to loved ones as if still facing the disappointments of childhood.

Let’s start with the title, Loving Like You Mean It. It suggests that some, maybe many, people go about the business of loving without putting much heart into it. What point are you trying to make with the title?

Great question. Loving Like You Mean It, is all about being able to open ourselves up emotionally, embrace our felt experience, and use it as a vehicle for connection—precisely what’s needed to build healthy, loving relationships. However, no matter how hard we try, many of us struggle to make love work with our partners. The problem is that our brains are running on outdated software. Without us knowing it, our early relationship programming causes us to fear being more emotionally present and authentic with our partners. We’re afraid to open up and step into our romantic relationships in a more honest and revealing way. Whether it’s the ability to give or receive love, manage and express anger, sadness, or shame, or acknowledge the need for closeness and security, our capacity to be emotionally present with our partners is hijacked by fear—and it is fear that is keeping us from having the kinds of relationships we truly desire. It’s fear that’s keeping us from being able to love like we mean it.

You are putting forth the case for emotional mindfulness. What is that and why it is important?

Emotional mindfulness applies the basic principles of mindfulness, or moment-to-moment awareness, to our emotional experience. Simply put, it’s about attending to, being present with, and making good use of, our feelings—both with ourselves and with others. While our early relational wiring is evident in the ways in which we respond to our feelings, the whole process is largely unconscious. We don’t realize what’s going on inside of us—that we’re having feelings and responding to them in unhelpful ways. We don’t realize that we’ve been triggered, and internal working models for dealing with our emotions in our relationships have taken over. Practicing emotional mindfulness serves as an antidote to our struggles by helping us to see and shift the emotional dynamics that have been unconsciously governing our behavior more readily. It grows our awareness of our feelings and increases our capacity to abide and work constructively with them. In turn, we’re better able to regulate our distress and objectively see and respond to what’s happening within us and before us.

You contend that we humans are wired to fear being emotionally present.

We’re actually wired to be emotionally present. That’s our birthright. But our attachment experiences, for better or worse, shape how we response to our emotions. For those of us who had caregivers who were uncomfortable with different emotional experiences, we learn to fear being emotionally open.

What does it mean to be emotionally present?

It means being present with ourselves, with what’s going on inside of us. Human beings are wired to respond emotionally to life and our experiences. Being emotionally present is about attuning to our emotional experience, working with and making good use of it, both within ourselves and in our engagement with others.

Why do we fear it?

Our fear is learned based on how our caregivers responded to us. As babies, as children, we’re utterly dependent on our caregivers to survive. When they respond negatively, it is experienced as a threat to our very existence. So, we adapt. We learn to avoid or mask the feelings that lead to disconnection and heighten those that seem to keep our caregivers engaged.

What purpose does it serve to not be emotionally present?

We avoid discomfort and the perceived threat that something bad will happen if we were to reveal more of ourselves. We respond to an old fear as if the danger still exists, and, for the most part, it doesn’t.

How does the lack of emotional presence manifest, and how does it play out day to day in relationships?

While our childhood threat of danger no longer exists, many of us unknowingly continue to respond to our emotions, relationship needs, and desires as if they’re dangerous. We end up repeating the same defensive patterns over and over—patterns that get us nowhere—as if we had no other options. In order to protect ourselves, we get caught in circular arguments with our partners, instead of taking the risk to share our hurt or fear. We minimize, deny, or hide our anger, pull away from our partners and avoid being direct, and then end up feeling resentful, disinterested, or depressed. Or, we fail to express the fullness of love in our hearts—and then can’t understand why our partners complain about feeling frustrated, alone, and unsure of our love.

Can you give an example of a common situation and how it is helped by emotional mindfulness?

Sure. They happen all the time. Our partner says or does (or doesn’t do) something and we have an emotional reaction. We go from stimulus to response in a nanosecond. A button gets pushed, and our default programming takes over. It all happens so quickly. But, if we could slow things down, if we could widen the gap between impulse and action, we’d afford ourselves some necessary space to be able to do things differently. When we’re mindful, we can see the path toward freedom. We can stretch the space between stimulus and response and make a choice more aligned with our greater good.

You argue that people have to change the way the brain is wired. Why?

Because, no matter how hard we try to change our relationship behavior, no matter how much we practice our listening, communication, or conflict resolution skills, if we’re not aware of what’s going on behind the scenes, sooner or later our nervous system gets activated, and we’re up to our old tricks again, no longer in control. The bottom line is this: No real change in how we operate or interact can happen until we recognize and learn how to manage what’s going on inside of us. We have to update our emotionally programming so that we have new, healthy ways of relating to our disposal.

To be devil’s advocate, isn’t the brain changing its wiring all the time, with all new behavior? What’s special about your plan?

Brain wiring is shaped by experience. But the kinds of experiences we engage in is crucial. The key to updating our relationship wiring in a positive way is in having new emotional experiences that allow us to grow and expand our capacity to relate with our feelings, needs, and desires, and, in turn, with our partners.

What specific efforts do you believe are required to change the wiring of the brain for love?

That’s my four-step approach to developing and utilizing the skills of emotional mindfulness that I detail in Loving Like You Mean It! Each of the steps addresses different efforts required to reprogram our software. In particular, with step one, “Recognize and name,” readers learn to identify when their old programming has activated their nervous system’s threat response so they can begin to break patterns of habitual responding. In step two, “Stop, drop and stay,” they learn to turn their attention inward and comfortably abide with and move through what’s happening inside of them without being reactive. In step three, “Pause and reflect,” readers learn to mine the wisdom that comes with being in touch with their truth, consider a now-broader range of options, and choose a course of action that is more aligned with their intentions and values. Lastly, in step four, “Mindfully relate,” readers learn how to manage the anxiety that comes with opening up in a new and different way, stay centered and present, and express their truth in a manner that paves the way toward healthier relating with their partners.

Can change by one partner shift the other partner, too?

Change can begin with just one person to help shift the relational dynamics in a positive direction. Instead of letting our defenses lead the way, we can allow our true self to emerge and step forward. Instead of acting out our feelings, we can be open and direct. Instead of getting overwhelmed or shutting down, we can take risks and do things differently. We can find a way to show the sides of ourselves we once learned to hide. We can express what we really feel, need, and want, and be emotionally present for our partners. When we mindfully share our core feelings, we give our partners the opportunity to know us more deeply and to respond in new and different ways. We maximize our relationship’s potential to be a place of growth and healing.

If you had one bit of advice to offer people in relationships, what would it be and why?

Grow your capacity for emotional mindfulness. Slow down, pay attention to, and make sense of your emotional experience before responding to your partner.

About THE AUTHOR SPEAKS: Selected authors, in their own words, reveal the story behind the story. Authors are featured thanks to promotional placement by their publishing houses.

To purchase this book, visit: