Vagus Nerve

Vagus Nerve Facilitates Guts, Wits, and Grace Under Pressure

The vagus-brain connection helps keep you calm, clear-headed, and courageous.

Posted October 15, 2017

Anxiety disorders have become a nationwide epidemic. In January 2017, the APA published their “Stress in America: Coping With Change” annual report which documented the first significant uptick of anxiety levels in the United States since the survey began ten years ago. This report also found that two-thirds of respondents regularly felt stressed out during their day-to-day lives and that "uncertainty about the future" was nerve-racking for most people.

Along this same line, on October 15, 2017, The New York Times Magazine published an article, “Why Are More Teenagers Than Ever Suffering From Severe Anxiety?” The subtitle of this article puts the conundrum of how best to cope with young Americans' anxiety disorders in the spotlight: “Parents, therapists, and schools are struggling to figure out whether helping anxious teenagers means protecting them or pushing them to face their fears.”

Over the past decade, anxiety has surpassed depression as the most common reason college students seek psychological counseling. The recent Times article notes that “The overestimation of danger and the underestimation of our ability to cope,” is a common definition for anxiety often heard at the non-profit, short-term residential Mountain Valley treatment center in New Hampshire for adolescent boys and girls struggling with OCD and anxiety disorders.

But there is some good news. In recent months, I've curated dozens of ways that people of all ages can learn to cope better with distress on a psychophysiological level by practicing some simple every day “vagal maneuvers” that activate the “relaxation response" of the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) by utilizing your vagus nerve.

The Vagus-Brain Connection Can Tame "Fight, Flight, or Freeze" Stress Responses

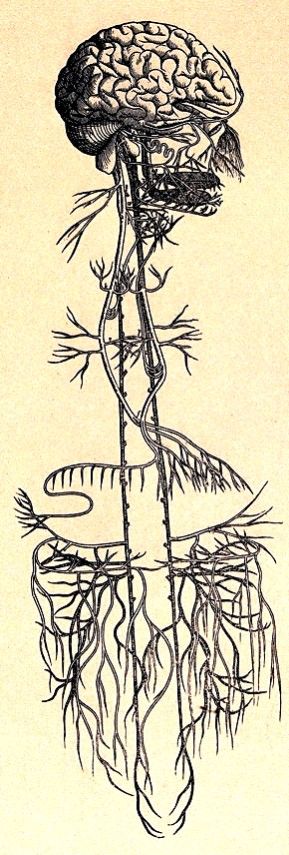

Vagus means "wandering" in Latin. The vagus nerve is referred to as the "wandering nerve" because it is the longest nerve in the human body and has multiple branches that begin in the brainstem and take a circuitous route to the lowest viscera of the intestines touching (and influencing) just about every major organ along the way. Your vagus nerve facilitates a constant psychophysiological dialogue between your mind, brain, and the milieu intérieur (environment within) of your body. The vagus also functions like a superhighway of communication via the bidirectional "gut-brain axis" feedback loop which sends messages "top-down" from brain-to-gut and "bottom-up" from gut-to-brain. Most importantly, in terms of coping with anxiety, the vagus nerve is the commander-in-chief of the inhibitory parasympathetic nervous system which counterbalances excitatory "fight-or-flight" stress responses to maintain homeostasis and grace under pressure.

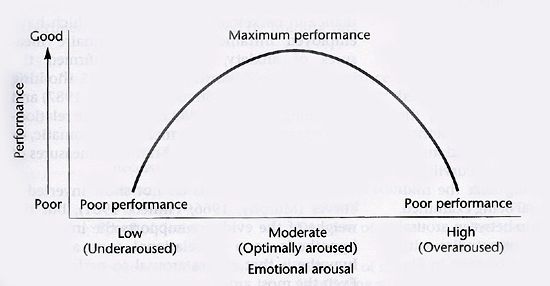

Historically, the parasympathetic nervous system has been compared to the brakes on a car because the PNS slows down the fight-or-flight stress responses of the sympathetic nervous system. The SNS is analogous to a gas pedal because it fuels anxiety by pumping adrenaline, cortisol, and other stress hormones into your nervous system. However, in recent years, it’s become clear that the ideal sweet spot within your autonomic nervous system is best represented by an inverted-U in which you are simultaneously secreting "tonic levels" of adrenaline and cortisol in a way that promotes eustress (good stress) and facilitates the oomph that is necessary to seize the day...while also pumping out acetylcholine and GABA which are endogenous (self-produced) tranquilizers that squelch anxiety and distress (bad stress).

For simplicity’s sake, when it comes to maintaining “Guts-Wits-and-Grace Under Pressure” (which is the working title of my next book) I like to focus on the yin-yang and dynamic push-pull of excitatory adrenaline and inhibitory acetylcholine as the two primary forces driving the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches of the autonomic nervous system respectively.

In 1921, when acetylcholine was first identified by Nobel Prize-winning physiologist Otto Loewi, he referred to this neurotransmitter as vagusstoff (vagus substance) because the vagus nerve appeared to squirt out something that slowed heart rate and calmed the nervous system like a tranquilizer. Later, psychophysiologists realized that slow, deep diaphragmatic breathing triggers a relaxation response by secreting this “vagus substance” (also known as acetylcholine) into the bloodstream.

Because vagusstoff instantly slows heart rate when someone exhales, measuring inter-beat Heart Rate Variability (HRV) is an easy physiological marker to gauge healthy vagus nerve activity and robust parasympathetic responses as marked by the production of acetylcholine along with increased vagal tone (VT) over time.

As an ultra-endurance athlete, I relied on monitoring my HRV as a practical tool to make sure I wasn’t overtraining. When an athlete doesn’t give him or herself enough recovery time between workouts, it throws the sympathetic nervous system into hyperdrive. This leads to a chronic state of fight-or-flight stress responses and systemic overactivity of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis (HPA axis). The same is true for anyone who perpetually pushes him or herself to the brink of burnout in daily life. By monitoring your baseline HRV, it’s easy to make sure that your vagus nerve is effectively counterbalancing the psychological and physiological strain of both “eustress” and "distress" by keeping your vagal tone high.

I first learned about the vagus nerve and vagusstoff as a young tennis player being coached by my late father, Richard Bergland, who was a neurosurgeon, neuroscientist, and author of The Fabric of Mind. Because my dad had to maintain “grace under pressure” during life-or-death brain operations and as a competitive tennis player, he kept a variety of psychophysiological tricks up his sleeve that he'd use to keep his nervous system regulated by consciously engaging his vagus nerve.

Diaphragmatic breathing and talking to himself using non-first-person pronouns to create self-distancing were his two favorite vagal maneuvers. To this day, anytime I play tennis, I speak to myself in the third person using my first name and recite the words my father pounded into my head before every serve: "Chris, if you want to maintain grace under pressure, visualize squirting some vagusstoff into your nervous system as you exhale slowly, while bouncing the tennis ball four times before each serve."

As a neuroscience-based tennis coach, my dad taught me how to use “vagal maneuvers” such as taking one deep diaphragmatic inhale, followed by one long, slow exhale as I relaxed the back of my eyes and bounced the ball methodically four times before every serve. This belly breathing and ball-bouncing ritual helped me stay calm and grounded while playing stressful tennis matches. Notably, the vagus techniques I mastered on the tennis court have always helped me stay calm, cool, and collected whenever I face daunting challenges or terrifying situations off the court, too.

The term “grace under pressure” first gained notoriety in 1929 when Ernest Hemingway used the phrase in a New Yorker profile piece, "The Artists Reward," written by Dorothy Parker. During their interview, Parker asked Hemingway: “Exactly what do you mean by ‘guts’?” Hemingway replied: “I mean, grace under pressure.”

Through the lens of the vagus-brain connection, I like the double meaning of "guts" referring to both courage and the GI aspects of our gut-brain axis. My ultimate goal when writing about “Guts-Wits-and-Grace Under Pressure” is to help readers who are prone to paralyzing anxiety learn how to tap into the power of their vagus-brain connection by using the parasympathetic nervous system to stay calm, clear-headed, and courageous in situations where they might have difficulty coping that often lead to avoidance behaviors.

Anytime the “fight, flight, or freeze” stress response of the sympathetic nervous system is unbridled and running wild, it’s easy to lose your ability to think clearly. Luckily, simply by taking a deep breath followed by a long, slow exhale you can harness your vagus nerve and release a dose of acetylcholine on demand. This helps give you the “wits” necessary to stay clear-headed and make wise decisions in times of distress.

In 2016, Igor Grossmann and colleagues from the Wisdom and Culture Lab at University of Waterloo published a paper, “A Heart and A Mind: Self-distancing Facilitates the Association Between Heart Rate Variability and Wise Reasoning,” which reaffirmed that vagal tone (indexed using HRV) was associated with superior executive functioning and wiser reasoning. As mentioned earlier, HRV is directly correlated with the vagus-brain connection.

Grossmann et al. hypothesize that adopting a self-distanced (as opposed to a self-immersed) perspective (which is also achieved by narrative expressive writing and using non-first-person pronouns) is correlated with higher HRV along with the ability to overcome egocentric bias which is often associated with neuroticism.

Lani Shiota, who founded the Shiota Psychophysiology Laboratory for Affective Testing (SPLAT lab) at Arizona State University, has identified that too much enthusiasm can backfire. Overarousal, as marked by a runaway sympathetic response, causes athletes to fumble, choke, and drop the ball.

Ideally, you want to simultaneously pump up the volume of excitatory adrenaline and inhibitory acetylcholine in perfect harmony to maintain guts-wits-and-grace under pressure. Additionally, the psychophysiological key to creating "flow" is to tap into a sweet spot of arousal that is between boredom and anxiety. This "mellow but excited" state of mind and body is directly linked to optimizing your autonomic nervous system.

Finding the sweet spot within your autonomic nervous system correlates with an optimal state of arousal, positive emotional valence, and chutzpah. Learning how to surf the "flow channel" between over- and under-arousal is key to stepping outside your comfort zones, facing your fears head on, and optimizing your human potential.

Some other vagal maneuvers you can use to engage your vagus nerve, reduce anxiety, and become "optimally aroused" include: Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA), mind-body interventions (MBIs) such as yoga, Quigong, or meditation, "tending and befriending" via face-to-face social connectedness, narrative expressive journaling, seeking out a sense of wonder and awe (this promotes "the small self" by realizing there's something much bigger than you out there), fortifying self-compassion and kindness towards oneself via LKM, creating a "flow state" by matching your level of skill with any challenge that pushes against your limits, having warmhearted, "simpatico" micro-moments with others (including strangers) throughout the day, and many more.

I'm optimistic that teaching people who are prone to anxiety how to harness the often underestimated power of the vagus nerve can improve our collective "sense of coherence" by giving everybody a reliable psychophysiological tool that is always at our fingertips, doesn't cost a penny, and is within the locus of each individual's control. To read more on this topic, check out my nine-part series “A Vagus Nerve Survival Guide to Combat Fight or Flight Urges.”

References

Shiota, Michelle N., Belinda Campos, Christopher Oveis, Matthew J. Hertenstein, Emiliana Simon-Thomas, and Dacher Keltner. "Beyond Happiness: Building a Science of Discrete Positive Emotions." American Psychologist (2017) DOI: 10.1037/a0040456

Grossmann, Igor, Baljinder K. Sahdra, and Joseph Ciarrochi. A Heart and A Mind: Self-distancing Facilitates the Association Between Heart Rate Variability and Wise Reasoning." Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience (2016) DOI: 10.3389/fnbeh.2016.00068

Piff, Paul K., Pia Dietze, Matthew Feinberg, Daniel M. Stancato, Dacher Keltner. "Awe, the Small Self, and Prosocial Behavior." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (2015) DOI: 10.1037/pspi0000018