Health

How Exercise Promotes Our Health and Longevity

We can modify our biochemistry with regular exercise to improve our health.

Posted March 10, 2020 Reviewed by Matt Huston

“Lack of activity destroys the good condition of every human being, while movement and methodical physical exercise save it and preserve it.” —Plato

“It is exercise alone that supports the spirits, and keeps the mind in vigor.” —Cicero

Although there are patterns and trends in human aging, how you age—and specifically the degree to which you maintain your function and vitality—is extremely variable from person to person and largely within your control. One of the primary ways you can influence your aging is through exercise.

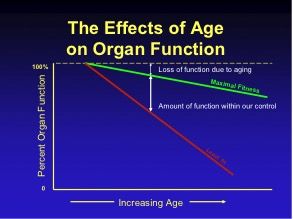

The figure to the left illustrates what we’re accomplishing with exercise. The green line represents the maximal potential performance for a given system such as the musculoskeletal system or cardiovascular system. In a healthy person, this curve is almost horizontal with minimal decrements over time. The position and slope of this curve are affected by various environmental factors. For example, cigarette smoking in youth may irreversibly reduce your respiratory potential in later years. The red line represents the rate of atrophy if the system is primarily in a resting state and never stressed. The system always functions at some point between the two curves.

The divergence of these lines over time leads us to three inferences. First, the natural declines that occur with age are generally of a lesser magnitude than declines associated with physical conditioning and environmental factors. Second, the possibility of significant decline increases as we age, so self-maintenance becomes more important. Finally, unless you are already in near-optimal condition, you have a greater opportunity for improvement as you grow older. For example, consider a very deconditioned person functioning near the lower red line. With exercise and improved physical conditioning the person could move up the functioning curve closer to the green line and function at a much higher level, perhaps even higher than sedentary younger people.

In addition to its effects on system functioning and quality of life, exercise is also one way to reduce your risk of debilitating diseases and premature death. For example, investigators in the Netherlands estimated that moderate exercise at age 50 increases lifespan by 1.5 years and high levels of exercise double that to more than three additional years. Moreover, exercise can reduce the likelihood of dependency. The average 65-year-old can expect to live about 13 more years without disability. Highly active 65-years-olds, on the other hand, remain disability-free on average for at least another 18 years.

Why Exercise Works

Exercise has potent effects on the body’s biochemical mechanisms of growth and repair, which are constantly counterpoised against the biological processes that cause decline and decay. Our biological systems are not static but are in a continual state of renewal.

When we are young, the default biochemical systems seem to be genetically programmed for growth and repair. As we age, decline and decay become the predominant biological effects. Without regular physical activity, a person’s muscles atrophy and he begins to walk with a slow and shuffling gait. He becomes short of breath with minimal exertion and feels less steady on his feet. Fortunately, this cascade can be minimized. In other words, the frailty we sometimes associate with old age is to a large extent preventable and even reversible. The key is to challenge your body through regular exercise. What you do and how long you do it makes a considerable difference.

Let’s delve a little deeper into the biochemistry of exercise to see how we can promote growth and repair and overcome the tendency for decline and decay. Inflammation is the body’s chemical response to insults and normally is a natural protective mechanism for healing. It can be a double-edged sword, however, and an overzealous inflammatory response is implicated in numerous common ailments. Inflammation stimulates chemical signals to initiate growth and repair to begin healing. At the same time, an associated biochemical cascade produces redness, swelling, heat, pain, and tissue destruction.

Exercise can harness the benefits of the inflammatory response. With each body movement, our muscles send chemical messengers to communicate with the rest of the body. A very important chemical signal related to inflammation is Interleukin-6 (IL-6). During an inflammatory response, the release of IL-6 is triggered by other chemicals, including Interleukin-1 (IL-1) and Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF)-alpha.

During exercise, IL-6 (and not these other chemicals) is released into the bloodstream with every muscle contraction. IL-6 appears to be anti-inflammatory when released from skeletal muscle in high concentrations without the TNF-alpha and IL-1 stimulation. Muscle contraction activates the genes controlling IL-6 production in a manner directly proportional to the amount of muscle being contracted: The more muscle is exercised, the more IL-6 is produced. In addition, the amount of IL-6 released increases as the muscle energy stores are depleted. Taken together, continuous muscle contractions and depletion of muscle energy can induce an increase of plasma IL-6 that is 20- to 100-fold over inactive levels.

Now here comes the important part. After about 30 minutes of continuous exercise, these high levels of IL-6 appear to flip a metabolic switch telling the body to burn fat, control energy regulation, and stimulate the growth and repair cycle through the release of IL-10. The good news is that the switch stays flipped for about 24 hours. As a result, the low background noise of decline and decay is reversed by the release of IL-10. This is part of the biochemical basis for the beneficial effects of exercise on reducing inflammation, improving glucose tolerance, and repairing body tissues.

By exercising daily for at least 30 continuous minutes we can shift the body’s underlying chemistry from decline and decay to growth and repair. The key concept is having continuous exercise, so three 10-minute walks do not add up to 30 minutes (although any exercise is better than remaining sedentary).