Leadership

The Hype and the Truth About Measurement-Based Care

MBC has had promise for a long time but it has never taken off.

Posted July 26, 2020

Measurement-based care (MBC) is the idea that patient care can be guided by systematic data collection. These data are supposed to directly inform treatment decisions and monitor client progress. MBC is considered one of the core components of a wider strategy to implement evidence-based practices covering both assessment and treatment (Scott and Lewis, 2015). MBC however does not have to be part of an evidence-based strategy; it can just be good practice for monitoring clients during any type of treatment.

I recently published a letter to the editor to show that data can be collected from patients to make decisions about their care much more effectively when clinicians are required to collect it as opposed to when it is voluntary (Scheeringa, 2020).

Researchers at the Washington University School of Medicine had published an earlier letter to the editor about their experience with collecting measures from patients at their child and adolescent psychiatry clinic (Liu et al., 2019). They had partnered with a local software development company to build an online portal for patients to complete intake questionnaires about their symptoms (e.g., depression, anxiety, etc.) and to repeat the questionnaires after receiving treatment in order to track treatment response. After one year of implementation, 54% of patients were completing intake measures. After three years their success had climbed to 71% and after five years to 78%. Impressive, but still missing over 20% of their clients.

Liu et al.’s success at getting patients to repeat the measures to track treatment response was, however, dismal. After one year of implementation, 11% of patients were completing repeat measures. After three years, their success had climbed to 39% and after five years, it stalled out at only 41%. You cannot monitor treatment progress if you do not collect the data.

Liu et al.’s letter is what prompted me to publish my letter to the editor to report the very different experience at my child and adolescent psychiatry clinic because we achieve so much better results. One year after we started collecting intake questionnaires, 96% of patients were completing intake measures as opposed to 54% at Liu et al.’s clinic. Over five years, our success remained above 90%.

More remarkably, our success at getting patients to repeat the measures to track treatment progress after one year of implementation was 88% compared to Liu et al.’s 11%. Our success after five years remained high at 92% compared to Liu et al.’s 41%. Why the big difference between Liu’s clinic and mine?

Voluntary versus Involuntary Cooperation

The collection of measures at my clinic is involuntary, whereas the collection of measures at Liu et al.’s clinic is voluntary.

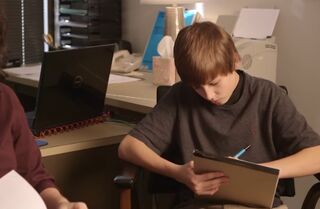

When I hire clinicians at my clinic, their contract stipulates that they are required to collect measures from clients at intake and then repeat those measures after approximately three months of treatment. When new clients arrive at my clinic, they sit in the waiting area and complete the measures before they are allowed to see the clinicians. There are very few exceptions. At first, we collected these measures on paper. Now, we collect them on a computer tablet. The whole process takes 15-20 minutes for most. In the rare instance that individuals have difficulty reading and the process takes longer, we will break it up and let them do it in stages.

The primary caregiver/legal guardian always completes measures. If children are 7 years and older, they also complete measures. For many children in the 7 through 10 years range, the clinicians often need to read the items and explain them.

When three months have passed, I place Post-it notes in clients’ charts (yes, we still use paper charts) as a friendly reminder to clinicians to repeat the measures. Sometimes it takes more than one Post-it note. It is a fair amount of work for me, but it is simple. This ain’t brain surgery.

We have collected data in this fashion on nearly 1,000 clients. Not a single client has complained to my knowledge.

Liu and colleagues replied to my letter to the editor. They argued that the distinction of voluntary versus involuntary was not the only important difference between our clinics. They work in a university-based clinic with multilevel institutional leadership (my interpretation: no single person is in charge), they deal with other quality improvement initiatives (my interpretation: MBC is not always a priority), their workforce is more diverse and includes many different disciplines with different degrees of acceptance of MBC philosophy (my interpretation: weak leadership), their patient volume is much larger than mine (my interpretation: they have not committed the personnel to monitor data collection); and their patient population is more diverse and may include individuals who may not be equitably served by data collection (my interpretation: some individuals have problems not captured on a questionnaire).

I do not have space in a blog post to reply to each of those differences, but none of them are impossible hurdles. It is also worth noting that some of those are not differences from my clinic. For example, my clinicians do not always want to collect measures. They do it because it is in their contracts. If clinicians lack the commitment to surmount those obstacles in larger clinic settings, MBC is doomed forever in those settings.

What It Means

Of course, it is easier to implement MBC in a small, privately-owned clinic compared to a large clinic in an academic bureaucracy. If anything, this difference helps us see both the possibilities and the limitations in different settings and might make it clearer about how things can move forward if they are ever going to move forward. At one end of the spectrum, in large and bureaucratically-controlled agencies, 40% compliance appears to be the wall with voluntary implementation. At the other end of the spectrum, 80% of psychotherapy businesses are solo practices (Curran, 2016) which are likely to have no support and little motivation to implement evidence-based practices. The future of MBC may be limited to small islands of committed practitioners until the industry gets serious.

References

Curran, J. (2016). IBISWorld Industry Report 62133: Psychologists, Social Workers, & Marriage Counselors in the US: IBISWorld.

Liu FF, Cruz RA, Rockhill CM, et al. (2019). Mind the gap: Considering disparities in implementing measurement-based care. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;58:459-461.

Scheeringa MS (2020). A Different Way to Mind the Gap: Mandated Versus Voluntary Collection of Measures. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, May 2020;59(5):576-577

Scott K, Lewis CC (2015). Using Measurement-Based Care to Enhance Any Treatment. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 2015 February;22(1):49–59. doi:10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.01.010.