Resilience

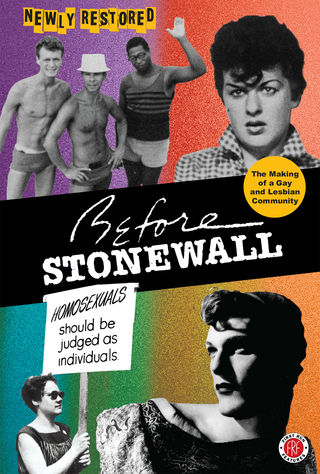

Film: "Before Stonewall" Explores LGBTQ Pain and Resilience

Re-released documentary shows why the 1969 riots happened and mattered.

Posted June 14, 2019

“You have to develop a tough hide to take care of the soft interior,” says Dorothy (Smilie) Hillaire, a Native American activist featured in the newly restored and re-released 1985 documentary film “Before Stonewall.”

She could have been speaking for everyone in her pre-Stonewall generation of lesbians and gay men who lived in closets, often leading double lives. Raising a family in the suburbs and leading a “down low” gay life in the city was even more common than it (still) is today.

In fact she could be speaking for LGBTQ people even today.

From our earliest years, as soon as we show any sign of being “different” from heterosexual boys or girls, LGBTQ people have it drummed into our very souls that different equals bad, sick, sinful, criminal, and second-class.

Self-appointed enforcers of social stigma to this day assault, fire, insult, preach against us, and even call for our execution. But as “Before Stonewall” so eloquently reveals, we also are among society’s most resilient.

Directed by New York filmmaker Greta Schiller and narrated by noted author Rita Mae Brown, “Before Stonewall” shows through firsthand interviews with women and men across the country that, long before the 1969 riots, LGBTQ people found ways to subvert the social stigma they met at every turn.

Even at a time when homosexuals were being routed from the federal government by the hundreds and the police regularly harassed us and raided our bars, gay men and lesbians of all colors, sizes, and socioeconomic backgrounds found ways to meet one another, carry on long-term romantic relationships (and plenty of short-term sexual ones, too), and simply enjoy being openly “different” among others who were different, too.

It’s important to understand what was at risk in coming out at the time, let alone living an “out” life. Homophobia was literally the law of the land. Sodomy laws prohibiting oral and anal sex for everyone were only enforced against gay men. Laws forbade homosexuals from associating with one another in state-licensed establishments, such as barrooms, in clear violation of the constitutional right to free assembly.

Legal stigma was simply the government’s stamp of approval on the heavy religious condemnation, reinforced as needed by citing the American Psychiatric Association’s classification of homosexuality as a mental illness. Anti-gay lawmakers and judges referenced the APA classification as “proof” that homosexuals were not “normal” and therefore were unworthy of equal citizenship.

Before Stonewall, most LGBTQ people didn’t have a sense that their sexuality had political implications, or that there might be a new, better way of living than inside a closet sealed by shame.

“There were only a few who were thinking beyond just having a good time or finding a personal lover,” says Jim Kepner in “Before Stonewall.” Kepner was an early member of the Mattachine Society, the group that pioneering activist Harry Hay began in Los Angeles in 1950 for gay men to meet and discuss their lives.

Legendary activists Frank Kameny in DC and Barbara Gittings from Philadelphia, and others in the budding pre-Stonewall equality movement, understood that changing the APA classification was essential to overturning the laws that kept LGBTQ people stuck in our second-class status.

Activists forced psychiatrists to confront the facts as presented in published studies of psychiatric researchers such as Evelyn Hooker, proving that homosexual men who weren’t under psychiatric care were as well-adjusted and functional as their heterosexual counterparts.

“What is difficult to accept (for most clinicians),” wrote Hooker in her game-changing 1957 article “The Adjustment of the Male Overt Homosexual,” “is that some homosexuals may be very ordinary individuals, indistinguishable from ordinary individuals who are heterosexual.”

Odd as it may seem looking back, gay men and lesbians debated whether it was better to be considered mentally ill than to be seen as deliberately choosing a depraved life of alleged immorality and crime.

“One of the more militant assertions put forward by Frank Kameny and other homosexual leaders was the idea that gay people were not mentally ill,” says the narrator, Rita Mae Brown. “Even within the movement this concept provoked intense debate.”

Many were so used to “covering” they thought it best not to rock the boat. Mattachine member Jim Kepner says in the film, “Many of us accepted the idea that if we dressed properly, if we behaved properly, if we didn’t make waves, if we didn’t draw attention to ourselves, people would accept us by not knowing who we were.”

That began to change. “We gradually, some of us, began to take the position that we had to assert ourselves,” says Kepner.

The stage was set by the time we get to the Stonewall riots that began the Friday night of June 27, 1969. “In the sixties, there was a distinct change in the temper and tempo of the gay movement, partly as a result of the black civil rights movement’s militancy,” says Barbara Gittings in the film.

“We began to get more militant in the gay movement. We began to see that the problem of homosexuality is not really gay people’s problem; it’s a problem of the social attitudes of the people around us. We had to change their attitudes and that in turn would help us with our self-image.”

The Stonewall riots marked the turning point when LGBTQ people seized control of the narrative about us. We stopped letting others define us by their twisted, dehumanizing homophobia.

Instead we began to tell our own story, to record our history, in our own voices. That is Stonewall’s greatest legacy: Coming out to ourselves, embracing the fact of our “difference” rather than wasting energy resisting it. Making ourselves the hero, no longer the victim of our stories.

The APA in December 1973 finally voted to remove homosexuality from its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, the bible of mental illness. It was one of the most profound early achievements of the post-Stonewall LGBTQ movement because it undercut the laws that discriminate against us.

And it came about precisely because gay men and lesbians refused to play by the old rules anymore, choosing instead to stand up for themselves and push back against stigma instead of turning it upon themselves.

“The whole film is about survival,” said “Before Stonewall” director Greta Schiller in a Skype interview for this blog. "Within it there’s a lot of lingering pain and struggle—and fear!”

There’s also a lot of resilience—something LGBTQ people know about because, as Dorothy (Smilie) Hillaire put it, “You have to develop a tough hide to take care of the soft interior.”

* * * *

Before Stonewall is a First Run Features release. Opening June 21 in New York City and June 28 in Los Angeles. Director: Greta Schiller. Co-Director: Robert Rosenberg. Executive Producer: John Scagliotti. Research Director: Andrea Weiss Editor: Bill Daughton. Narrated by Rita Mae Brown.