Memory

Impeachment Hearings and the Dim Light at Tunnel's End

Is there anything positive to say about our partisan divide?

Posted November 14, 2019 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

The impeachment hearings are underway. It reflects a continuing polarization in American politics. This polarization started long before Donald Trump took office and there is no end in sight. The impeachment hearings, like the Ford-Kavanaugh hearings, are perhaps another example of America's growing inability to understand itself.

What can we learn from this? Are there bigger messages about the psychology of cultural and political self-construction? American governance was created to defend itself from enemies from within, but who are the enemies and what, if anything, is the bright side of identifying them? Are we not divided enough? It helps to understand where this division comes from.

The political polarization of our age was partly fueled by and may have begun with the Vietnam War. The Vietnam War was a national dissonance created by a government willing to say one thing while believing another. That government was perhaps too preoccupied with other things to consider that, like the American Civil War, people have to pick sides on these issues and the sides they pick can have lasting historical and political implications. The polarization Vietnam created has grown over time and it affects people's perception. People with strong ideological views see distorted versions of reality, versions that tend to support their predispositions and lead to further polarization (Hills, 2019).

America's growing incapacity to recognize any truth is evidenced by growing party unity. Or, in other words, an unwillingness to vote across party lines. If truth were evident to anyone who looked, then decisions would be more about individual appeals to rational consideration of the facts. There is no reason to believe a Republican, Democrat, or any member of any party would have more access to the truth than someone else. But when political divisions start to invade one's rational consideration, then people stop looking like individuals and start looking like their political ingroups.

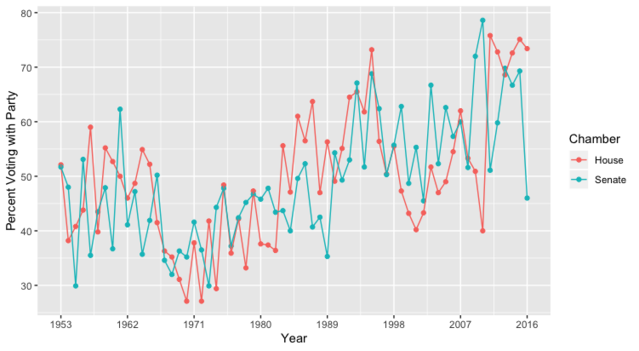

The figure I've created here is from Brookings Vital Statistics on Congress. It clearly shows a rising tide in the average percentage of votes where individuals in the House and Senate vote with their party. The rise starts near the end of the Vietnam War when the inevitability of losing that war was sitting squarely on nightly television. Surely other things fueled this divide, but the Vietnam War is one cultural legacy we can't overlook. The psychology of that legacy is unfortunately understudied.

Looking at the figure, the answer to the old question "If all your friends jumped off a bridge, would you jump too?" is clearly more of a yes now for America's political representatives than it was in the past, much to America's detriment.

One is tempted to see the impeachment as an extension of this growing partisan divide. The psychological research on interpersonal conflict shows that when grievances arise, each side tends to bias the evidence in ways that support their own position. A study by Baumeister and colleagues found that perpetrators and victims basically build dual worlds of facts to justify their opposing positions. Victims see violence towards them as arbitrary and gratuitous and often coming in a long series of injustices. Perpetrators, on the other hand, feel their actions are provoked, justified, and one-off events effectively designed to "correct" imbalances.

The implication may be that no one has objective access to the truth and all sides are equally wrong. However, that is the wrong take-home message.

The "there is no truth" argument is exactly what the guilty side of any argument would like you to believe. By muddying the waters, questioning the legitimacy of the process, and attacking people instead of arguments, attacking witnesses instead of evidence, perpetrators effectively throw "objective" onlookers into confusion. This often leaves us feeling less certain about our ability to believe anything. As a consequence, we feel less conviction towards any decision, we feel helpless and less concerned with the outcome. That's what the guilty party wants you to feel.

Violence among Hong Kong protestors, misinformation campaigns against the White Helmets in Syria, and the treatment of Christine Blasey Ford as an individual as opposed to a considered reflection of her testimony are all instances where expert manipulators benefit from confusing things. Anger towards people who call out your mistakes is not a desirable attribute of good leaders or good governance. Climate change skeptics and the Intelligent Design community have benefited from similar obfuscations. This kind of misinformation is getting easier. Anonymous mechanisms for rapid dispersal of online misinformation, targeted at individuals in the style of Cambridge Analytica (no relation to Cambridge of any kind), are leaving things looking bleak for the rise of "reason."

However, we don't have to see it this way.

An alternative and assured optimistic view is to see the recent history of American political contests as developmental. But then you have to ask, development towards what?

One narrative is this: A once proud but over-represented minority is slowly losing its power to a historically under-represented minority, who is having to fight a failing system for the right to its representation.

The over-represented minority use privilege, capital, and manipulation to construct mechanisms for keeping what's "theirs." Arguments to lower taxes on the wealthy in America, which were once as high as 70 percent, are based on solidly disproven assertions based on things like the Laffer Curve and trickle-down economics.

A multi-billion dollar company wouldn't think twice about reinvesting in itself. But many Americans don't see a need for reinvesting in America. The crumbling of the facade they see around them is directly related to that and without a prudent government, they are likely to blame it on one another. Reinvestment in Americans of all kinds is exactly how to make America great again. But that isn't a story that many people with the means to correct this problem will want you to hear.

The narrative of wealth redistribution is, of course, only a semantic game. Who in America minds that Californians pay more into federal taxes than they get in return while other states tend to get more back than they pay? Is that wealth redistribution or simply the cost California must pay to stay in the land of opportunity?

The narrative is changing though. The obfuscation by some politicians is evidence that the over-represented are on the ropes. Perhaps the old political truth is dying as a new political truth is taking shape. One political truth in America is about gerrymandering (which I've written about here), which is a symptom of more general inequalities. However, that is the history of many governments.

The electoral college, which must be explained again and again to high school students because it is ultimately undemocratic, is simply another example of this. The explanation usually involves pointing to a map of the U.S. and showing how states (and a lot of unoccupied land) deserves a vote too, otherwise, the few people in that land will be taken advantage of. The sad logic of this: the electoral college increases the total number of people being taken advantage of because it reduces the value of the majority of people's votes. So, the majority of the people get a fraction of a vote. While select minorities get their whole vote plus a little extra.

It can't be at all surprising that the people who benefit most from America's gerrymandered system are willing to fight to continue it. But if the fight gets sufficiently well-developed, it can get ugly. When it does, that usually means the tides are changing. Or, that they'll need further reinforcements.

When the African National Congress gained sufficient support in South Africa, violence, uprising, and international condemnation eventually led to negotiations and the changing of the guard when the African National Congress won the election in 1993 and Nelson Mandela became president. That wasn't a smooth transition. A notable highlight was when the right-wing neo-Nazi Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging ran an armored car through the glass of Kempton Park World Trade Centre where the negotiations were taking place.

Things don't always work out as nicely as they did in South Africa. According to Ian Kershaw's recent history of modern Europe, Roller-Coaster, when Hungarians rose up against Soviet rule in 1956, Soviet troops marched on Budapest, killing approximately 22,000 Hungarians and arresting around 100,000 people. This changed the political view of communism amongst communists around the world. For many, it moved from one of a utopian communist ideal to one of top-down military enforcement.

It seems irrational to imagine similar futures for a democratic America. But the impeachment is about the legitimacy of our democracy. That is already in question. According to the Electoral Integrity Project, America is 55th of 158 nations in electoral integrity (last among Western democracies). It isn't a joke that many Russians think American democracy is a farce.

Trump, elected by the gerrymandered American electoral system, is now under siege by the House for further violating America's democratic integrity. The Conservatives feel the need to defend him. We can rest assured that if Conservatives ran the House, they would see similar actions in a Democrat president as impeachable. The perpetrator-victim gap is alive and well in government.

The testimony so far in the impeachment has taught us and will continue to teach us what we already know. William Taylor, a U.S. diplomat, and George Kent, a State Department official, both working on U.S. relations with Ukraine, testified that Trump made military aid for the Ukraine contingent on Ukraine publically initiating an investigation into Trump's political rival.

Trump has already admitted to this, so we're learning the details of his actions and the context under which they took place. Can we expect to learn more? It seems doubtful. Whatever the witnesses say, the Democrats are likely to consider it the last straw, and Republicans are likely to minimize it.

If partisan voting continues, and why shouldn't it, one can predict already that the Democrat-ruled House will impeach Trump. And the Republican-ruled Senate will ignore this and continue to defend the status quo. For either to not do that would be political suicide.

It will be extremely surprising if anyone crosses party-lines in this vote. All of Trump's efforts thus far to turn Republicans against him have failed. Even his recent pulling of U.S. troops out of Turkey was quickly forgotten, despite at least a few momentary upset tummies among Conservatives. It is sadly a form of Stockholm Syndrome at a national level, where the hostages have become endeared to their captor.

By the time the next U.S. election rolls around, this impeachment may be nothing more than a distant partisan memory. But if it is a harbinger of what is to come, then this may be another "last stand" in a long list of last stands against inequality. It will be over, one hopes before the armored car crashes through the glass doors or the tanks rumble in the streets.

References

Hills, T. T. (2019). The dark side of information proliferation. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(3), 323-330.