Teamwork

Developing a Science of Interrogation

Effective Interrogation Relies on Sound Moral Principles

Posted September 10, 2015

By Christopher E. Kelly

When discussing the “science of interrogation,” the following disclaimer is critical: This post will be about the science of humane and ethical interrogation that has the goal of eliciting verifiable, actionable intelligence and/or true confessions. To be sure, such a science has been practiced for at least the past two decades, particularly with regard to distinguishing the factors leading to true versus false confessions in a law enforcement context. In recent years, however, the science of ethical interrogation in human intelligence gathering (HUMINT) and counterterrorism interrogation has blossomed due to the federal government’s interest in this research area for the first time in more than a half-century.

Soon after his inauguration, President Obama signed Executive Order 13491 that created a Special Task Force on Interrogations and Transfer Policies that ultimately lead to the creation of a new interagency collaboration called the High Value Detainee Interrogation Group (HIG). In addition to its operational duties, the HIG was tasked with creating an unclassified program of research to evaluate best practices in lawful interrogation. Since that time, researchers from the United States, Europe, Australia and elsewhere have been working to fulfill the Task Force’s mandate and a science of humane and ethical interrogation has begun to emerge. In collaboration with Allison Redlich and Jeaneé Miller, I have been part of the HIG’s research agenda since its inception, and the remainder of this post will summarize the research we have been working on.

My colleagues and I were initially tasked with developing a systematic survey to be deployed online to the operational community of military and criminal interrogators, investigators, and HUMINT gatherers in the United States and later, around the world. The purpose of the survey was to establish a sort of baseline of information about the methods interrogators use and perceive to be effective with uncooperative sources, detainees, or suspects. To be sure, there are differences between HUMINT and law enforcement interrogations, especially in their goals or outcomes, but to date no systematic investigation into actual practices has conclusively found that what these various practitioners do dramatically differs.

From the earliest days of reviewing foundational work in interrogation and investigative interviewing, including the Army Field Manual 2-22.3 and manuals such as the “Reid Technique,” we realized that little standardization existed in the language used to describe and research interrogation methods. For instance, techniques that would appear operationally similar to one another would be defined differently across the works (e.g., minimization) depending on the context in which it could be employed. As such, we sought to identify a “lexicon” of interrogation methods in order to capture the entire spectrum of them in a research context, something that hadn’t previously been done.

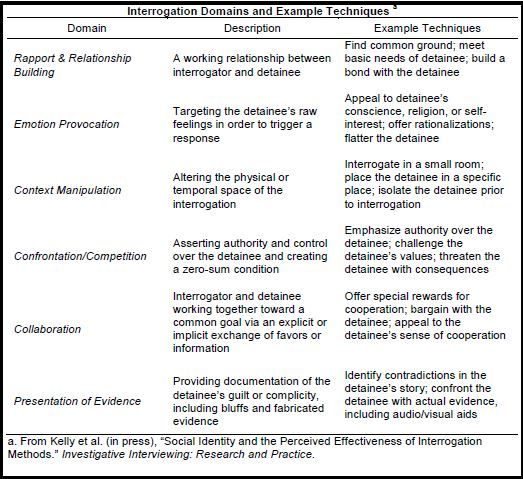

This effort lead to the publication of “A Taxonomy of Interrogation Methods” that differentiated between “macro” level dichotomies such as rapport-based / control-based interrogation, friendly / harsh, or maximization / minimization and the “micro” level specific techniques that are very refined in their definitions. We argued that neither the macro nor the micro levels were very useful in describing and studying interrogation, as the former is too broad and the latter too narrow to have much value. Drawing upon Col. Steven Kleinman’s (USAF-Ret.) writings on the Army Field Manual, we identified six “meso” level domains that are conceptually distinct from one another and sorted more than 60 specific techniques into one of each: rapport and relationship building, emotion provocation, context manipulation, confrontation/competition, collaboration, and presentation of evidence. [See BOX for domain definitions and examples of constituent techniques for each.]

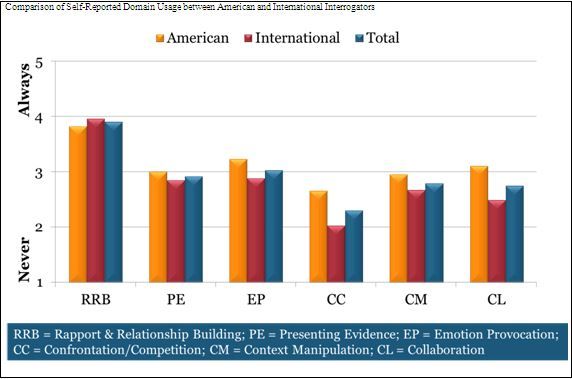

Having identified and defined the six domains that represented the breadth of interrogation methods (not including torture, of course), we were able to incorporate them into the survey in order to examine their self-reported rate of use by practitioners and, importantly, their perceived effectiveness relative to one another when the interrogation goals and scenarios were varied. In total, approximately 300 American and international practitioners completed the survey as a result of invitations sent out by professional societies and through our professional networks. We found that rapport and relationship building was reported to be significantly favored by the survey participants in general and confrontation/competition to be least employed, regardless of the goal (e.g., intelligence gathering, confession/prosecution) or scenario that was depicted in one of three interrogation vignettes. With regard to differences between law enforcement and other types of interrogators, we found few significant differences in their self-reported practices. Finally, Americans were significantly more likely to employ the emotion provocation, confrontation/competition, and collaboration domains relative to practitioners from Canada and other European nations. See CHART for between-group comparison results.

Next, we applied the taxonomy and domain framework to a sample of suspect interrogations supplied by the Robbery-Homicide Division of the Los Angeles Police Department (RHD-LAPD) to evaluate the use of methods in a real-world setting. In general, the rate at which LAPD interrogators employed the domains was remarkably similar to those from the self-reported survey. Further, when we distinguished between those interrogations that ended in full or partial confessions and where suspects denied their guilt entirely, we found that both the presentation of evidence and confrontation/competition were significantly and substantially more likely to be emphasized among the suspects who denied guilt.

Lastly, in a paper that is currently under review, we are advancing what is known about interrogation by analyzing the “dynamic” nature of it. By this we mean that the phenomenon is a fluid one, where what the interrogator does and how the suspect responds changes over the course of an interrogation, and the extant research has not begun to capture the complexities inherent to interrogation. (For a description of how this is done and graphs demonstrating the difference between “static” and “dynamic” examinations of interrogation, please see an earlier post at the CVE/HUMINT blog.) For instance, using a measure of suspect cooperation as our dependent variable, we found that rapport and relationship building significantly increases cooperation but that emotion provocation, confrontation/competition, and presentation of evidence significantly decreases suspect cooperation. Furthermore, in statistical models, the negative effect on cooperation of the confrontation/competition domain lasts for fifteen minutes, controlling for the other domains employed in the interim. Without question, these findings on the dynamic nature of interrogation do not account for variables related to either the interrogator or the suspect, and the results only begin to account for the reciprocal effects of interpersonal interactions (i.e., whether and how the interrogator employs certain methods based on suspect behavior). Much more research is clearly needed into the incredibly complex dynamic of interrogation.

In sum, we are finding that the parsimonious six domain framework is useful for research in terms of describing what interrogators do and what is related to relevant outcomes such as cooperation and confession. There is much work, however, to go in terms of refining the definitions and indicators (i.e., techniques) of the domains and especially their utility in the areas of training, practice, and policy. We hope that others are interested in such endeavors and encourage them to challenge our assumptions, replicate or refute our findings, and continue searching for the best language and methods that contribute to the science of interrogation.

***

Christopher E. Kelly, Ph.D., is an assistant professor in the Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice at Saint Joseph's University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (USA). He received his doctorate in criminal justice from Temple University and was a postdoctoral associate in the School of Criminal Justice at the University at Albany. While there, Dr. Kelly worked on three related data collection efforts funded by the High Value Detainee Interrogation Group (HIG), including as Principal Investigator on a project entitled "The Dynamic Process of Interrogation," a content analysis of video and audio recorded interrogations. Currently, Dr. Kelly is leading a field experiment with the Philadelphia Police Department that examines how the context in which police interviews affect interviewees’ information disclosure and cooperation. Dr. Kelly has been published in Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, Criminal Justice and Behavior, Justice Quarterly and the Annual Review of Law and Social Science, and he is a member of the American Psychology-Law Society (APLS) and the International Investigative Interviewing Research Group (iIIRG). He can be contacted at c.kelly@sju.edu.

All opinions and analyses presented here are the author’s and do not reflect official policy or position of the HIG, FBI, or the U.S. Government.