Sleep

Does Our Fear of Sleep Mirror Our Fear of Death?

Many have ruminated about the connections between nightly sleep and final sleep.

Posted August 19, 2018

My father-in-law died recently and, sleep-health being my life's mission, I couldn't help but ruminate on the similarities between sleep and death. My husband, Mark, exhibited no fear whatsoever as he stroked his dad’s forehead, turning a cool washcloth there and whispering, “We love you, Dad, we got you, Dad. It’s okay to let go.” I fell in love with my guy all over again. When I asked him about his stalwart gentleness in the face of his father’s final sleep, he answered, “I have no regrets.” Mark had left nothing unsaid in the living years which left room for such tender intimacy in death.

Most Americans don't do death well – same with sleep. Does our sleep anxiety mimic our death anxiety? Might this be a reason so many Americans suffer from disordered sleep?

According to the American Sleep Association (ASA), 50 – 70 million Americans have a sleep disorder and nearly 40 percent of Americans suffer from insomnia. I think those numbers are under-reported.

I grew up with intergenerational trauma, alcoholism and violence, and I developed sleepwalking and night terrors that haunted me for twenty years, affecting every aspect of my life. Trauma and disordered sleep are inextricably linked. My first somnambulant episodes began in adolescence. Yet long before my family reported such incidents, there was the feeling of impending doom. Going to bed carried with it a kind of animal fear. The despair I felt at leaving this world behind, of separating myself from the people I loved, was all-consuming. I am certain of these feelings, yet my earliest memories of sleep are watery, elusive. One thing is for certain: I was hypervigilant and would have stayed up all night if my body had allowed it. Insomnia. Only my family chalked up my sleep dread to normal childhood fears; I was simply being a baby, as in babyish, a scaredy-cat, spoiled. This mindset was not uncommon as so many babies boomed.

Sometimes my oldest sister, 11 years my senior, tried to help me settle into sleep. I wished I could have taken her into sleep with me. When all else failed, we played our favorite bedtime game where she hummed “The Funeral March” by Chopin while ever-so-slowly pulling the blankets up over my face like a dead little girl being laid to rest. As she approached the end of the musical phrase and once my head was completely covered, she popped the covers off: “Boo!” We found the ritual hysterical and broke into peals of hushed laughter. Eventually, my sister had to leave me and, as I stared at the ceiling for what seemed like hours, I would feel my body grow cold—a real, live, dead girl.

Our culture has grown so far from caring for our dying. There was a time when families would nurse sick or elderly relatives at home and care for their bodies after death, in preparation for funeral services and burial. I recently came across an article about a practice during the Victorian era, when photography was new. It's called post-mortem photography, and while it might strike us as terribly morbid, it was quite popular during the 19th Century. Families would enlist photographers to take pictures of their deceased relatives, most often depicted as sound asleep. It helped those left behind to grieve.

Could my sister’s and my gloomy bedtime game have been our way of trying to make sense of the pain of the separation we faced in going to sleep? Were we playing at death while awake, knowing, but dare not naming, that we’d soon be playing at death in sleep?

This brings my thoughts back to my husband, Mark, and his amazing ability to remain present in the face his father’s death. I met Mark after my own close brush with death—just a few days after the accident I had during a sleepwalking/night terror episode that literally brought me to my knees. I’d broken my nose, almost lost my front tooth, my bottom two teeth had pierced my upper lip, and I had a concussion. Before meeting Mark, I’d gone to any lengths to hide my sleep disorders from men. I was a freak and chose isolation over intimacy. The shame was so strong, I almost let Mark think that I had been abused or attacked rather than that my injuries were self-inflicted while sleepwalking. (You can read more about the incident here.)

Maybe growing up the oldest of eight children had cultivated Mark’s sensitivity. Maybe the death of his sister when he was 12 had nurtured his empathy because on the night of our third date, when I let burst the truth behind my bruised face all he said was, “Do you want to tell me about it?” Then he put his arm around me. For a few moments, we just sat side by side. It was a relief not to be looking directly into his face. He stroked my hair. I closed my eyes. I was tired all the time. I recalled one definition of surrender—to join the winning side. Mark held me through that night as I told him my story. Just as I was becoming willing to truly face and release the illness that had stolen twenty years of sleep and left my face battered, just as I was becoming willing to release the self-violence and seek proper help, I’d met this man who modeled gentle love.

While I can still struggle with insomnia, I have been fully recovered from sleepwalking and night terrors for decades. Over the years, I have often pondered our culture’s fear of sleep and likened it to our fear of death. I'm quite aware that my own sleep health and recovery from trauma, one day at a time, is due in great part to my husband's love. I am blessed and privileged.

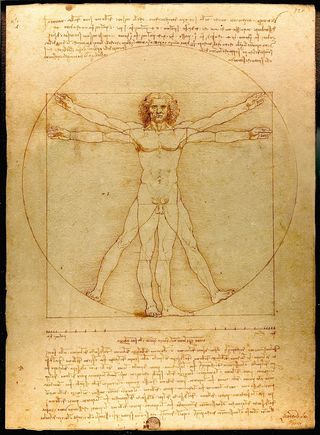

Many writers and artists have ruminated about the connections between nightly sleep and our final sleep. One of my favorite such quotes is from Leonardo da Vinci: “As a well-spent day brings happy sleep, so a life well spent brings happy death.”