Psychiatry

The Rebel’s Clinic: A Book Review

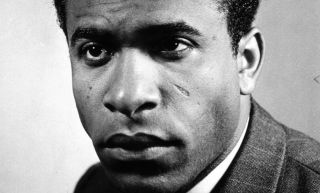

A biography of Frantz Fanon examines the psychiatric clinic he ran in Algeria.

Updated April 10, 2024 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- How could the psychiatrist treat his patients’ psychic wounds while fighting against their dehumanization?

- Support for social psychiatry led to critiques of ethno-psychiatry and its ties to colonialism.

- Renowned for rejecting racism, Fanon made the struggle for justice and for mental health inseparable.

.png.jpg?itok=wf-Z2YCX)

“In front of the sick, we are filled with humility.” With these quiet, reflective words, murmured to trainees during hospital rounds, the Martinican psychiatrist Frantz Fanon conveyed a profound sensitivity to his patients during Algeria’s harrowing eight-year battle for independence.

“We were enormously impressed,” the Tunisian sociologist Frej Stambouli recalls, “by his ability to listen to his patients and his art of making them talk without fear.”

The fifth of eight siblings—likely named “Frantz” after his mother’s Alsatian roots—a now-28-year-old Fanon had been appointed director of Algeria’s Blida-Joinville Psychiatric Hospital in 1953, a year after the publication of his watershed psychological treatise against racism, Black Skin, White Masks. The country would soon be embroiled in violent conflict, and his staff and patients would be forced to live in “an atmosphere of permanent insecurity.”

As Adam Shatz explains in his deft and engrossing biography, The Rebel’s Clinic: The Revolutionary Lives of Frantz Fanon (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2024), many of Fanon’s patients “lived through brutal roundups in villages, escaped from mass executions, withered away in refugee camps, or survived ruthless interrogation.” Many told him of family members who had been “killed, tortured, or raped by French soldiers” and of their own guilt and shame if they responded with comparable violence.

“A Laboratory of Revolutionary Ferment and Innovation”

Fanon had been entrusted with running a clinic inside the psychiatric hospital that would be “open at all hours to fighters in need of both physical and psychological care.” Since at other national hospitals, “wounded Algerians faced the risk of being turned over to the police,” the clinic quickly became indispensable.

While the physical symptoms Fanon and his colleagues treated were mostly mild—stomach ulcers, impotence, muscular stiffness, and difficulty sleeping—the worst effects of the conflict were intractably mental: “nightmares, feelings of murderousness or despair, a paralyzing sense of depersonalization.”

As a doctor, Fanon “did not discriminate between Algerians and Europeans: all, in his view, deserved compassion and care.” The fact that at Blida-Joinville soldiers, even torturers, were entitled to counseling nonetheless led to tense dilemmas. One resulted in a ghastly encounter between an Algerian patient traumatized by torture and the French officer responsible for it, who was seeking reprieve from associated guilt and shame. Fanon describes finding the officer “leaning against a tree, covered in sweat,” in the full throes of a panic attack.

[Fanon] drove the man home; on the sofa, the man explained that he had stumbled upon an Algerian who had been tortured at police headquarters. Fanon learned afterward that the officer had himself tortured the patient in question and that, after the encounter, the patient had gone missing. “We eventually discovered him hiding in a bathroom where he was trying to commit suicide,” Fanon wrote in his case notes. “The Algerian victim was convinced that his torturer had come to the hospital to arrest him.”

Other reforms at the clinic were endearing and meant to be pragmatic but failed to win over skeptics. “Since many of his Muslim patients had been farmers,” Shatz writes, Fanon “encouraged them to grow vegetables and gave them spades and picks to plant a garden in a soccer field.” But a cry went out about the patients’ reduced space for exercise. A senior administrator who “considered [the Martinican] ‘madder than the madmen’ called the gendarmerie, and a barbed wire fence was erected around the field until Fanon forced them to take it down.”

Rejecting the Culture of Psychiatric Confinement

Black Skin, White Masks, first published in Paris, worked to expose racist and colonial assumptions and projections—the structural-political consequences, Fanon explained to Richard Wright, of “systematic misconceptions that exist between Whites and Blacks.”

But in Algeria, during the brutal colonial war that put cities under siege and made civilians frequent targets and hostages, Fanon’s focus shifted increasingly to the disalienation of the racially oppressed and dispossessed. In doing so, his clinic faced difficult questions: How could it best treat their psychic wounds while fighting against their dehumanization, not least if treatment meant a return to violent conflict?

In “Social Therapy in a Ward of Muslim Men,” one of several papers from the clinic co-written with Jacques Azoulay, Fanon’s intern and close friend, social psychiatry was embraced—as it had been by Wright in the United States a few years earlier—as a tool for liberating the poor and oppressed. Yet, in this case, the emphasis on “social therapy” had additional effects, including to “demolish” (in Shatz’s words) “the mythologies of a racist psychiatry by revealing what lay beneath the ostensible pathologies of Algerians: a stubborn psychological resistance to colonial domination, rooted in an attachment to national identity and tradition.”

The clinic at Blida-Joinville gave Fanon a chance to apply some of his most progressive policies, to help restore soldiers to health while serving the independence struggle. It built on close precedents such as the Lafargue Clinic—founded in Harlem, New York, in 1946—which for 12 years served residents and sought “not only to heal the wounds of racism but also to challenge the racist biases of American psychiatry.”

Strongly opposed to “shielding” patients from the world, a process Fanon believed would lead to ‘thingification’ of their condition, he advocated a “more dynamic, confrontational approach to care,” in which patients were encouraged “to faire face au monde (confront the world),” even if it challenged their understanding of a still-colonial reality.

As Shatz observes, Fanon nonetheless “came to see that reform was not just inadequate but also a lie—that, short of a revolutionary transformation, he would be complicit as a practicing psychiatrist in the culture of confinement that sequestered Algerian bodies and souls.”

There were practical considerations, too, tied to language and translation. Since, at the time, Fanon spoke neither Arabic nor Berber (he began Arabic lessons in 1956), “he often depended on interpreters—Algerian nurses, for the most part—to communicate with his patients.” His work with Algerians was thus “a work of constant translation” risking its own, milder forms of misrecognition and misunderstanding.

Throughout, Fanon is described as exacting, involved, and demanding of himself and his staff. As Shatz puts it, “He always arrived at work before his interns, dressed in fastidious shirts with cuff links, and sometimes changed his tie twice a day. After dinner, he would often meet with staff to discuss Freud’s clinical studies or the latest developments in psychiatric research.”

The False Universal in a Colonial War

Part of the lesson from Fanon’s clinical focus, Shatz writes, was that “psychiatry in a colonial society had to draw on the lived experience and the values of the colonized: it could not impose a foreign culture as a universal one.”

It could not do so successfully, that is, but many of its adherents still tried. Since the “universalist method” was in fact based on French norms and culture, as Fanon soon grasped, it could neither “reach” his traumatized patients nor mask that such ethno-psychiatry had its own roots in colonialism.

The Rebel’s Clinic is adept at examining what Fanon proposed in its place and, thus, an invaluable record of how his thinking and practice evolved. One such example is the regressive stance on homosexuality that he had adopted in Black Skin, White Masks—a stance that was widespread at the time. According to Shatz, Fanon’s perspective later shifted “in a markedly less normative direction in Tunis, thanks in part to his work with a mentally disturbed gay man, one of the only patients with whom he attempted a traditional psychoanalytic treatment.”

“Refusal of the Mask”

A psychiatrist trained in Lyon and a careful reader of Lacan on fantasy, projection, and symbolization, Fanon helped to “map the psychic landscape produced by racism” with a focus on what we now call “implicit bias.” As Shatz concludes, “His psychological insights into the humiliations of colonial rule, the violent (and erotic) fantasies of the colonized, and the arrogance of the national bourgeoisie were not only piercing but also rich in dramatic potential.”

The Rebel’s Clinic asks excellent questions of its subject, from practical and conceptual tensions in his writing (especially notable in the shift from Black Skin, White Masks to The Wretched of the Earth). One such tension emerged “between his work as a doctor and his obligations as a militant, between his commitment to healing and his belief in violence.” Why, too, was Fanon “so averse to Paris, with its vibrant Black community”? Why did he choose Lyon for his training, “a city notorious for its suspicion of outsiders”? Above all, given the ferocious counterinsurgency the French army unleashed in Algeria and Fanon’s affirmation of violence in response, “Had rhetoric like Fanon’s helped to reinforce the resort to violence to settle political problems?”

Shatz is certainly correct in noting that “patience with the Gandhian model of resistance was running out.” Over the course of the bloody eight-year war, the same model was indeed revealed as vastly inadequate. But was a third way still possible that Fanon, with well-noted truculence and a now-vast audience, too quickly dismissed as unworkable or undesirable?

The counterfactuals persist: What if The Wretched of the Earth had opened not with its incendiary chapter “On Violence” (which Sartre’s preface mistakenly glorified, derailing the book’s larger argument and reception) but with its harrowing final chapter, “Colonial War and Mental Disorders,” among Fanon’s most trenchant criticisms of colonialism as the source of violence?

Fanon himself would later acknowledge that some of his incendiary rhetoric was meant to rouse and shame what he called the “beautiful souls” of the French left, whose purism could lead to apathy. He was also, Shatz notes, “explicit in his criticisms of a politics based on revenge: the revolutionary movement’s obligation was to direct the violent impulses of the colonized toward pragmatic objectives, not to foment bloodletting.”

Instead of trying to resolve these tensions—in either case impossible or revisionist—The Rebel’s Clinic lays out the contraries that pulled its brilliant protagonist in competing directions: “The partygoer and the ascetic, the rebel and the dutiful psychiatrist, the ambitious striver and the selfless militant, the urbane intellectual who romanticized the peasantry, the opponent of France who believed fervently in its revolutionary Jacobin traditions, the nomad who never stopped looking for a home.”

Fanon Today

While assessing Fanon’s legacy and continued relevance, including for countries and regions still enduring colonial war, Shatz concludes: “The era of alternative facts and hypernationalism has been a breeding ground for the racialized fears that Fanon diagnosed so brilliantly… The racial divisions and economic inequalities that he protested were not so much liquidated as reconfigured.”

In Italy, for example, where his work has “enjoyed unusual prestige,” Fanon has inspired a clinic named in his honor, the Centro Frantz Fanon in Turin, whose “patients are mostly migrants and refugees, often victims of trafficking or torture.”

In the States, where Fanon’s work was widely adopted by the civil rights movement and for years has been integral to postcolonial and diaspora studies, his writings more recently helped to inspire the Black Lives Matter movement and redirect attention to police violence and disproportionate incarceration, following the deaths by the police of Eric Garner, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd.

References

Shatz, A (2024). The Rebel’s Clinic: The Revolutionary Lives of Frantz Fanon. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.