Genetics

Being Adopted as An Adult Healed Me. DNA Testing Did Not.

In the 21st century, genetic similarity is an obsolete way to define family.

Posted September 21, 2021 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- DNA testing services can be interesting but also potentially problematic, as they can illuminate dark family secrets.

- Genetics do not have to define a relationship.

- Adult adoption is one method for choosing one's own own family in the modern era.

I am one of those people who uncovered a dark family secret through modern DNA testing. Several years ago, I submitted my genetic profile to a DNA service, largely to learn about my risk for future diseases. For example, neurodegenerative disorders run in my family, and through this testing, I discovered I have a 51% chance of developing Alzheimer’s myself.

Since I was submitting my profile anyway, I also signed up to be alerted when DNA relatives were found. For the longest time, the nearest matches listed were a few third cousins. Then one day, I received a notification that the system identified someone with a DNA profile extremely close to mine. She and I shared enough DNA that it was possible we were first cousins. There are a number of other genetic relationships that would be possible; for example, she could have been the half-sibling of one of my parents. Although we didn’t know for sure, one thing was clear: There was a secret both of our families had been hiding.

We couldn’t say definitively what the nature of our genetic relationship was, but the various scenarios presented with differing degrees of likelihood. Given the limited information she and I did know, we determined which one was the most probable. And it was one that called into question whether my biological grandfather was actually a particular man who was not my grandmother’s husband. I was able to confirm that my grandmother knew this man, which seemed to solidify this theory.

For some time, I grappled with believing my grandfather probably wasn’t who I’ve always believed and I came to peace with that. It was especially difficult as it was a burden I carried alone. I did not want to hurt anyone in my family by sharing this possibility with them.

Several years down the line, more information has come to light and it turns out we may be able to exclude this particular man as the direct source of my DNA. The remaining possibilities could still include, for example, that one of this man’s brothers is my biological grandfather. In the tight knit Italian neighborhood of the 1950s, there’s a good chance my grandmother would have known this man’s other family members in addition to just him. Or, although less likely, it could be that one of my grandparents had a full sibling unbeknownst to the family, and possibly to my grandparent themselves.

My relatives found out about this secret independently of me, so if I chose to pursue it, I’d no longer have to face it alone. They are working to confirm which scenario is the true one and I could join them in their quest. But I’ve made a decision: I don’t care.

What may or may not have happened 70 or 100 years ago doesn’t matter to me now. It doesn’t change who I love, or who I am. I chose to marry my wife, my wife and I chose bring my daughter into this world, we've assembled an "inner sanctum" of surrogate brothers and sisters, and I even had the rare opportunity to choose my own father. That experience stands in stark contrast to all of these challenges with having allowed genetics to define me.

When my mother passed away from brain cancer at the age of 57, I felt not only that loss, but the loss of no longer being legally related to my stepfather, Aaron. Far more than any other man, since my adolescence Aaron has been there to support me and shape me into the adult I am.

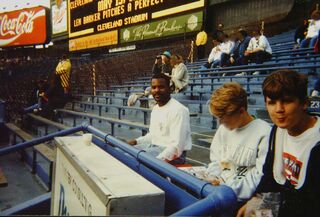

I’m very fortunate to have found him. My mother and I lived alone together since I was 2 years old. She suffered from severe mental health issues, including psychosis, suicidality, and command hallucinations which she believed to be the devil instructing her to kill me as a baby. Her mental disability meant that we were often on welfare and food stamps, and frequently lacked basic necessities like utilities. Beginning when I was 9 years old, I had to pull a wagon full of newspapers through the Cleveland snow every morning before school to help support us.

But, in the early '90s, there was a breakthrough: Prozac had led a new generation of psychiatric medications which were much more effective. Up until this point, my mom was largely unmedicated. She had previously been on the only medications available, which all had tranquilizing effects. When she overdosed on them to attempt suicide, the doctors cut off her supply.

But the new medications were not only more effective but also safer. They stabilized her and allowed her to be at her best. She was able to get a job which she held for many years, she went to college, eventually earning her master’s degree, and she met the man who would become my stepfather. He’s been a consistent source of support and warmth ever since.

So some time after my mom died, although I was around 32 years old, I asked him to adopt me. It’s been a wonderful experience. I have him, officially and legally, as my father, and my daughter has him as her grandfather.

Many people seem unaware of adult adoption as an option. But I’d encourage everyone in similar circumstances to consider it. Not only does it mean so much emotionally to have that validation of our relationship, but there are logistical benefits as well. For example, years from now, when he is an old man and I’ll have the privilege of caring for him, a hospital’s visitor policy of “family only” will be no barrier.

Choosing my father through adult adoption enhanced my life, while struggling with my genetic heritage diminished it. The former was an exercise in autonomy and agency, while the latter left me feeling that I was a powerless heir to conflicts created by other people’s choices made in a far off time and place.

I remember reading about Ronan Farrow’s disinterest in knowing his paternity when he stated, “Listen, we’re all ‘possibly’ Frank Sinatra’s son” (Reuters, 2013). At the time, I couldn’t understand his indifference. But as I reflect on my two contrasting family experiences, I completely get it. A focus on genetics keeps us stuck in the past and distracts us from our relationships in the here and now.

I’m not averse to knowing the outcome of my family’s investigation into its heritage, but neither do I feel the need to seek out that knowledge. Genetic information is interesting, it can be fun, and it can connect us to others to form new relationships. But it’s also ultimately only as meaningful as we allow it to be. That’s just one of the valuable lessons I’ve learned from my father, Aaron.

References

Reuters. (2013, October 4). Actress Mia Farrow says Frank Sinatra could be father of her son. Reuters. Retrieved September 20, 2021, from https://www.reuters.com/article/entertainment-us-miafarrow/actress-mia-….