Trauma

Can Brain Function Predict Future Risk for Psychological Distress?

Understanding risk and resilience to psychological symptoms following trauma.

Posted March 16, 2022 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- Trauma exposure is common and can have diverse psychological impacts on individuals.

- Novel research on brain-based biotypes following traumatic stress can help us understand future risk for psychological symptoms.

- Research suggests that there may be two distinct pathways to PTSD symptoms that may benefit from different treatment approaches.

Trauma touches almost everyone. Approximately 90% of Americans will be exposed to a traumatic event in their lifetime and the public health significance of trauma is clear in the vast negative mental health consequences that can occur following exposure.

As a trauma researcher and clinician, I see the diverse ways that trauma impacts individuals. One common reaction is post-traumatic stress disorder or PTSD. Other common psychological consequences include depression, anxiety, and substance use problems.

Yet, we still have a lot to learn about how to identify those most at risk for developing psychological disorders following acute trauma exposure and how best to allocate limited behavioral health resources to those most at risk. One challenge is the dependence on diagnostic constructs to inform risk predictions.

Scientists have turned to the brain for answers on the biological bases of these varied trauma responses and to discover brain-based profiles that are agnostic to diagnostic labels. Research led by Dr. Jennifer Stevens, a neuroscientist from Emory University and co-director of the Grady Trauma Project, collected data on 146 individuals as part of a nationwide longitudinal study of trauma exposure and subsequent mental health outcomes, the Advancing Understanding of Recovery After Trauma (AURORA) study1.

Using neuroimaging, Stevens and her team examined neuroimaging profiles in the period right after trauma occurred and investigated how those post-trauma biotypes related to the emergence of psychological symptoms in the months following trauma2. What is unique about this approach is that the post-trauma biotypes are not dependent on a particular diagnosis or symptom and instead provide a brain-based model of individual differences in response to traumatic stress.

How the study worked: Two weeks after trauma, investigators scanned 146 adults using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to look at brain response to fear, reward, and inhibition tasks. Psychological symptoms were measured for the first six months post-trauma.

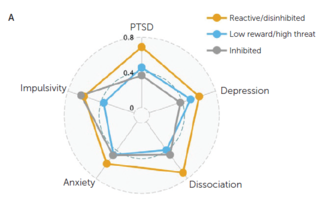

What the study showed: Looking across two separate samples, three biotypes were found and replicated and showed differences in psychological outcomes:

1. Reactive/disinhibited → high levels of PTSD and anxiety symptoms.

2. Low reward/high threat → PTSD symptoms, high startle response.

3. Inhibited → resilient, low threat reactivity and high regulatory activation.

These findings suggest that there may be two distinct pathways to PTSD symptoms that may benefit from different treatment approaches.

There has been a strong push in the field to move beyond a focus on diagnoses and take more mechanistic and transdiagnostic approaches to understanding mental health and disorders. One example of this is RDoC, a research framework put out by the National Institute of Mental Health for investigating mental disorders that focuses on basic biological and cognitive processes underlying dysfunction in broad domains of human functioning3. Another example is the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP) system4, a model developed by scientists to organize psychological symptoms into a more cohesive taxonomy that reflects existing data on psychopathology.

Both of these frameworks are meant to help improve the precision and impact of research on mental disorders and ultimately lead to important advances in treatment. One illustration of a transdiagnostic treatment approach is the Unified Protocol for the Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders5, which combines elements of evidence-based practices across mindfulness, cognitive therapy, and behavioral therapy, and allows clinicians to flexibly work with patients to learn new ways of responding to uncomfortable emotions. This treatment helps reduce focus on specific disorders and instead directly addresses underlying mechanisms that influence symptoms across disorders.

What does this study mean for clinical practice? We are a long way off from being able to use brain scans as a tool for identifying risk in a hospital or clinic-based setting. But, this approach provides an opportunity to study risk and resilience to traumatic stress in a whole new way and may serve as a helpful model for future prospective traumatic stress-related risk studies.

References

1. McLean, S. A., Ressler, K., Koenen, K. C., Neylan, T., Germine, L., Jovanovic, T., ... & Kessler, R. (2020). The AURORA Study: a longitudinal, multimodal library of brain biology and function after traumatic stress exposure. Molecular Psychiatry, 25(2), 283-296.

2. Stevens, J. S., Harnett, N. G., Lebois, L. A., van Rooij, S. J., Ely, T. D., Roeckner, A., ... & Ressler, K. J. (2021). Brain-based biotypes of psychiatric vulnerability in the acute aftermath of trauma. American Journal of Psychiatry, 178(11), 1037-1049.

4. Kotov, R., Krueger, R. F., Watson, D., Achenbach, T. M., Althoff, R. R., Bagby, R. M., Brown, T. A., Carpenter, W. T., Caspi, A., & Clark, L. A. (2017). The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP): A dimensional alternative to traditional nosologies. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126(4), 454-477.

5. Barlow, D. H., Harris, B. A., Eustis, E. H., & Farchione, T. J. (2020). The unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders. World Psychiatry, 19(2), 245.