Relationships

The Gut-Punch of Rejection: Literature Tells It Like It Is

Reading about fictional rejections can help people process painful emotions.

Posted April 24, 2023 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- A rejection can feel like a physical blow that takes one's breath away.

- Vivid literary descriptions of rejections invite readers to imagine sensations deep in their bodies.

- Reading evocative stories about rejection may help rejected people heal.

Recently I experienced rejection, but the first half of this sentence can’t convey how it felt. In the moments when reality prevailed, the truth stopped my breath like a martial arts kick to the chest. The blow didn’t come from the person for whom I had developed feelings. He merely exercised his human right to say no, a right I’ve invoked many times myself.

I had misread his communications. As Junot Díaz says of Beli in The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, “Like lovergirls everywhere, she had heard only what she wanted to hear” (Díaz 137). Compared to Beli, I had little to complain about. I wasn’t pregnant; I hadn’t been entered, hit, or even touched. But when I knew I was unwanted, I couldn’t breathe—for a few seconds, anyway. Only reading stories helped.

“Rejection” is a violent word that speaks directly to the body. It derives from the Latin jacere, “to throw,” which, when combined with “re-,” means “to throw back” (“reject”). Examples of its past use include vomiting (“reject”). This verbal history reflects people’s tendency to feel rejection in their core, as though they were falling, suffocating, imploding, or flying toward a fetid heap of trash.

Reading about fictional people who experience these feelings can bring comfort if an author describes these sensations well. Literary scholar Lisa Zunshine has proposed that people read fiction to exercise their theory of mind and their capacity to imagine what other people think and feel (Zunshine). Sharing a character’s emotions becomes easier if descriptions help them resonate in readers’ bodies.

Literary scholar Ellen Esrock has observed that readers’ responses to intense descriptions need not involve visual imagery. Their engagement with a story might be more visceral, affecting bodily rhythms such as breathing (Esrock 79-80). When describing a devastating rejection, authors may encourage interoceptive imagery—in other words, they may invite readers to imagine how their innermost organs would feel if they were in the character’s place.

The most memorable literary responses to rejection involve pain that runs deep. Pregnant and unwanted like Beli, Gretchen in Goethe’s Faust asks the Virgin Mary, “Wer fühlet, / Wie wühlet/ Der Schmerz mir im Gebein?” (“Who feels how the pain digs into my bones?”) (Goethe, 114, my translation). Both of these impoverished female characters feel fear amidst their devastation since their wealthier lovers want no part of their coming children. Aggravating this fear, the pain of feeling unwanted seems to bore into Gretchen’s bones.

Whether real or fictional, responses to rejection depend greatly upon context. Since the 1980s, psychologists have found evidence that children raised by people who made them feel safe and loved can more easily find secure attachment in romantic relationships, whereas children who were neglected, abandoned, or abused are more likely to avoid or mistrust attachment in adulthood (Hazan & Shaver 511; Mandal & Latusek). When it comes to rejections, feeling unwanted by one’s parents can predispose one to generalize. “No, thanks” from one individual can feel like a confirmation that the world doesn’t want one to exist.

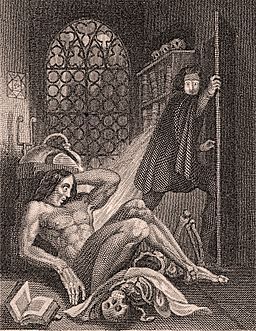

Such is the case in one of literature’s most egregious rejections, Victor Frankenstein’s denial of his creature in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Despite his hard work building the creature, Victor flees from him, refusing his pleas for love and guidance and calling him a fiend. Shelley offers readers the creature’s perspective so that they can experience that rejection with him.

When he is beaten and repulsed by the De Lacy family, from whom he has hoped for friendship, the rejection becomes more than he can bear. He confesses that “my heart sunk within me as with bitter sickness,” and “I gave vent to my anguish in fearful howlings. I was like a wild beast that had broken the toils; destroying the objects that obstructed me” (Shelley 110-111). The De Lacys’ violent response to the creature forms one of several rejections that have followed Victor’s, and to help readers share the creature’s feelings, Shelley describes his sinking sensation, his howls, and his violent movement. All her references draw a reader’s mind into his body so that one can almost feel his pounding heart, his diaphragm-driven howls, his flailing, and his impression of sinking. For good reason, he believes that no one wants him, and the truth expresses itself in his heart and lungs.

Catherine Sloper in Henry James’s Washington Square feels her rejection just as viscerally. The second child of a prominent New York doctor, Catherine becomes the target of his anger after his beloved wife dies following her birth and their son dies as a toddler. Like the creature, Catherine is made to feel ugly, awkward, and unwanted from the time of her birth. When attractive Morris Townsend courts her, she is eager to believe that she is loved. The evidence mounts, however, that Morris wants only her money. When he learns her father has largely disinherited her for becoming engaged to Morris, he leaves her abruptly.

Inviting readers into Catherine’s consciousness, Henry James writes: “She flung herself on the sofa and gave herself up to her grief… she felt a wound, even if he had not dealt it; it seemed to her that a mask had suddenly fallen from his face. He had wished to get away from her; he had been angry and cruel, and said strange things, with strange looks. She was smothered and stunned” (James 185). Loss of hope for love pains Catherine like a bodily wound. Feeling annihilated as her dream disintegrates, she cannot draw a breath, as though she were being crushed by an external force. She finds the strength to recover, however, and becomes socially respected for her wisdom and judgment. When Morris returns years later to propose marriage, she turns him down.

In American culture, people suffering from rejection often hear that they should move on. The call not to linger or reflect may take the form of well-meaning hints or impatient demands. Under this pressure, many people injured by rejection suppress rather than think through their pain. They may perform "moving on" to please those around them while trying to live with unhealed wounds. Reading well-written stories of rejection can reassure a person that someone understands. By addressing the mind and body at once, authors like Díaz, Goethe, Shelley, and James show readers that they don't just know what rejection means; they can feel it.

To recover from rejection, one needs to pull back and view a relationship—and all of life—from a broader perspective. Commands to do so can feel insulting. When you are hurting, being told that you're seeing things narrowly can feel like another kick in the gut. Healing begins with understanding and with realizing, on one's own timescale, that one is ready to view a situation from another angle.

One could start with the viewpoint of the rejecter, who has a right to say no and may not be as bad as Beli's Gangster, foolish Faust, narcissistic Frankenstein, or mercenary Townsend. Genuine healing doesn't come from pretending to move on and hoping one's emotions will follow. Real recovery requires honoring and understanding your own emotions along with those of others, starting with your bodily core and moving outward toward the world.

References

Díaz, J. (2007). The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. New York: Riverhead Books.

Goethe, J. W. von. (1986). Faust. Edited by Erich Trunz. Munich: C. H. Beck Verlag.

Hazan, C. & Shaver, P. (1987). “Romantic Love Conceptualized as an Attachment Process.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 52, no. 3, pp. 511-524.

James, H. Washington Square. (1986). Edited by Brian Lee. New York: Penguin Books.

Mandal, E. & Latusek, A. (2014). “Attachment Styles and Anxiety of Rejecters in Intimate Relationships.” Current Issues in Personality Psychology, vol. 2, no. 4.

“Reject.” (1983). Concise Oxford Dictionary. 7th edition. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

Zunshine, L. (2006). Why We Read Fiction: Theory of Mind and the Novel. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press.