Coronavirus Disease 2019

Disregarding Science: The Politics of COVID-19 Beliefs

When political beliefs contradict science, the results can be deadly.

Posted March 28, 2020 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

"Well, I think the Dow was helped by the fact that there were theories that we're going to stay out for four or five months, and you can't do that as a … you destroy our country if you did a thing like that. And we're going to be opening relatively soon. Our time comes up, Monday or Tuesday are the allotted two weeks, but we'll stay a little bit longer than that.

"But we want to get open very soon ... I'd love to have it open by Easter, OK ... I would love to have it open by Easter. I will tell you that right now. I would love to have that. It's such an important day for other reasons, but I'll make it an important day for this too. I would love to have the country opened up, and they're just raring to go by Easter."

—President Donald Trump, a virtual town hall (3/24/20)

"Let us work together in the most bipartisan way possible to get the job done as soon as possible. It won't happen unless we respect science, science, science. And for those who say we choose prayer over science, I say science is an answer to our prayers."

—Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, press conference (3/26/20)

Political beliefs are ideological beliefs. And yet, in politics today, ideology doesn't so much predict political affiliation as political affiliation predicts ideology. While we may choose our political party affiliations based on where we stand on core issues like abortion, immigration, or gun control, where there are stark divides, many of our feelings about those issues are predetermined by the families and communities in which we grow up. Furthermore, once affiliated with a party or political perspective, we tend to adopt all of the beliefs that are part of that party's platform, as if learning and adopting the playbook of a sports team.

So it is that we can often predict where someone stands on the issues of the day by their political affiliation. It, therefore, came as little surprise that in the microcosm of my own social media feed this month, I noticed that it was my conservative friends who were the ones who disagreed with the emergent consensus of public health epidemiologists, infectious disease experts, and physicians and instead wrote about how COVID-19 might be a hoax, that it's "just like the flu," or that we're overreacting by imposing strict social distancing rules across the country.

Indeed, a number of recent polls by Axios, Civiqs, NBC News/Wall Street Journal, Pew, Reuters, and Quinnipiac University have all confirmed that concern about COVID-19 is greater among self-identified Democrats than Republicans (this summary suggests that, on average, 65 percent of Democrats are either somewhat or very concerned about catching the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus compared to only 38 percent of Republicans), while Republicans are much more likely to believe that social distancing is an unnecessary overreaction.

And while that difference may be narrowing as the number of COVID-19 cases have increased (on March 26, the U.S. overtook China as having the most confirmed cases of any country in the world), with conservatives like Newt Gingrich urging concern and President Trump pivoting from talking about hoaxes to acknowledging a pandemic, the difference persists. For now, at least.

Many of us already concerned about COVID-19 are wondering just how many people have to die for conservatives to pivot en masse. In a recent Washington Post article, "In a Pandemic, Political Polarization Could Kill People," NYU psychology professor Jay Van Bavel refers to that pivot point as a "reality constraint" on beliefs. In other words, people can disregard reality for a remarkably long time according to motivational reasoning, at least until it comes butting right up against their own personal lives.

But it may be some time yet before that happens. As Ronald Brownstein highlights in his Atlantic article, "Red and Blue America Aren't Experiencing the Same Pandemic," COVID-19 is currently concentrated mostly in U.S. urban centers that tend to be more politically liberal. The divide between COVID-19 attitudes is therefore not only political but also geographic, such that until COVID-19 finds its way into America's heartland, some will continue to dismiss it as a metropolitan scourge (independent of politics, there has also been a seemingly obvious generational divide such that young people, who already think of themselves as invincible and appear to be much less at risk of death from COVID-19, can dismiss it as a geriatric disease with cavalier comments like, "If I get corona, I get corona").

A recent article by University of West London professor of evidence-based health care Heather Loveday, drawing from an earlier "epidemic psychology model" based on the AIDS pandemic,1 outlines how the psychological response to COVID-19 can be broken down into distinct attitudes about fear, explanation, and action.2 This distinction allows us to look more deeply at the political divide over COVID-19. Attitudinal differences aren't only related to fear of infection or death; there are also significant partisan differences about the cause of and best response to COVID-19.

According to this perspective, those unconcerned about COVID-19 are writing it off as a disease of "others," just as AIDS was originally written off by many as a "gay disease." For Republicans, blaming COVID-19 on "China" (and the insistence on calling it the "Chinese virus" or "Wuhan virus") has become a well-established strategy, whether because of legitimate complaints about China's failure to contain the initial outbreak or false rumors about SARS-CoV-2 being created in a lab as a bioweapon. On the other side of the political divide, liberals counter that the U.S. response to COVID-19 has been at least as bad as China's, if not more so, and that xenophobic disease attributions are far more harmful than helpful.

Mirroring those causal attributions, differences in attitudes about optimal COVID-19 responses also play into the current political divide over race and immigration. Conservatives are more likely to believe that isolationism in the form of "building walls" and travel bans is the answer to COVID-19, if not everything else that ails us.

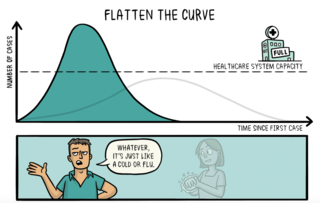

In contrast, liberals are more likely to look to science experts for guidance on just how concerned we should be and about optimal solutions to things related to science, whether we're talking about COVID-19 or climate change. Thus far, the rate of infectious spread of SARS-CoV-2 and death from COVID-19 has tracked almost exactly with predictive mathematical models, underscoring why—until herd immunity, vaccines, or established treatments for SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 are available—social distancing is absolutely necessary to "flatten the curve" and minimize deaths, and why letting up on those efforts now would be very foolish indeed.

Conservatives' mistrust, disregard, and hostility towards science have been something of a deliberate strategy over the past few decades that has become intertwined with the Republican party's current populist narrative that dismisses scientists as arrogant elitists who don't understand the common man or have his best interests in mind.

Of course, lest we fall into the trap of black-and-white thinking about American partisan politics today, the political divide over COVID-19 shouldn't be over-stated. After all, almost 40 percent of Republicans are concerned about COVID-19, just as 35 percent of Democrats are unconcerned about it. In the final analysis, it, therefore, makes more sense to frame differences of opinions over COVID-19 according to science and anti-science beliefs, rather than a matter of conservatives and Republicans vs. liberals and Democrats.

It's been said that there are no atheists in foxholes, suggesting that we all reach out to God in the face of death. But similarly, when we're sick, most of us reach out to science and medicine for salvation. Sometimes we reach out when it's too late. Indeed, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic now, rejecting scientific consensus in favor of anti-science attitudes can be deadly.

Science isn't perfect and isn't always right. Far from it—it's not a dogma; it's an iterative process of acquiring knowledge that we can trust. When it comes to COVID-19, trust the process. Trust science. Lead with science.

If there's to be any hope for saving lives, it lies in the science and in the efforts of those who have embraced science in their careers—the doctors, nurses, and many other health care workers putting themselves in harm's way, fighting on the front lines against COVID-19 and the misbeliefs that fuel its spread.

To read more about differences in attitudes towards COVID-19:

► Why Aren't Some People Taking COVID-19 More Seriously?

► From Angst to Ennui: Adjusting to Life During COVID-19

► The Deadly Effects of COVID-19 Misinformation

References

1. Strong P. Epidemic psychology: a model. Sociology of Health & Illness 1990, 12:249-260.

2. Loveday H. Fear, explanation and action – the psychosocial response to emerging infections. Journal of Infection Prevention 21:44-46, 2020.