Spirituality

Flat Earthers: Conspiracy Thinking on a Global Scale

The beliefs of Flat Earthers go well beyond the shape of the planet.

Posted July 5, 2018

On the heels of a Psych Unseen blogpost from last year entitled, "Flat Earthers: Belief, Skepticism, and Denialism," I've since fielded a number of media interviews on the subject. Here's the full transcript of one of those recent interviews:

► As you noted in your recent article in Psychology Today, we can mean different things when we talk about “belief.” In what sense do flat-earthers actually “believe” that the world is flat?

Indeed, it has been argued, both in philosophy and psychology, that there are qualitatively different types of belief. For example, there’s faith — choosing to believe in something in the absence of evidence — and belief based on evidence that is objective, observable, and repeatable, in the tradition of the scientific method. Often things aren’t so cut and dry, however — conspiracy thinkers often see themselves as believing based on scientific evidence, but are heavily swayed by confirmation bias in the service of faith in some other guiding principle, such as a core mistrust of conventional wisdom. This allows wide swaths of established scientific knowledge to be brushed aside in the process of “searching for the truth.”

Beyond attempts to categorize belief into types, other models suggest that differences in beliefs aren’t so much qualitative as quantitative, differing by degree along dimensions like conviction or preoccupation. Or in the degree to which we’re influenced by different cognitive biases. I think many who identify with the Flat Earthers, especially those that appear online or in media interviews (e.g. Kyrie Irving), aren’t actually as convicted as they appear to be at first glance. They may or may not actually believe in a flat earth, but are instead affiliating themselves with the growing general attitude that we should be questioning facts at every turn and placing trust in our intuitions. That said, there are certainly some Flat Earthers that truly believe, with high levels of conviction, the Earth is flat. Some of the most well-known examples are literally making a career out of being a flat earther, but then we have to wonder whether some of these folks, like InfoWars’ Alex Jones, are essentially performance artists who profit from promoting conspiracies and who sometimes influence others to become true believers.

► It would seem that just gathering evidence to refute the idea of a flat earth isn’t enough – because what we would see as evidence, a flat-earther would reject. Is that a fair statement?

Many beliefs that we hold are notoriously resistant to counter-argument. That is, by definition, most true of delusions seen in mental disorders like schizophrenia, but imperviousness to reason is part of religious faith and other types of normal belief. Having “cognitive flexibility” — the ability to take appreciate different perspectives and find middle ground — is mentally healthy, but it’s not necessarily a quality that most people possess in spades.

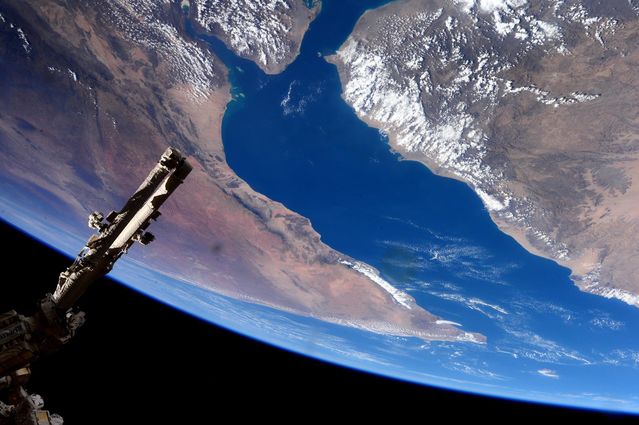

Last year, I was interviewed for a documentary on Flat Earthers called Behind the Curve, which recently premiered at the Hot Docs film festival in Toronto. During part of the interview that ended up on the cutting room floor, I commented that I would love to see a Flat Earther purchase a SpaceX ticket to “see for themselves” what the earth looks like from above 35,000 feet and beyond. But I had to agree when the directors questioned whether some die-hard Flat Earthers would even reject that personal experience. Indeed, if you look online, you’ll see some people suggesting that the Earth’s atmosphere acts as a spherical lens that gives the illusion of curvature.

Without giving away too much more of what’s in the movie, I thought the filmmakers did an excellent job of showing how some Flat Earthers were performing legitimate experiments to test their hypothesis and how they reacted when the results didn’t fit their theories. Another interesting revelation in the film is that there are significant disagreements among prominent Flat Earthers and in a few cases, those disagreements have led to accusations that one or another Flat Earthers is actually a NASA mole. So there certainly is a quality among some Flat Earthers of being able to refute every and any potential counter-argument.

► If round-earthers and flat-earthers can’t even agree on what counts as evidence, is there anything at all that can be done? It seems like it might be an automatic dead-end.

One thing to keep in mind about Flat Earthers is that the core belief isn’t just about whether the Earth is round or flat. Believing that the Earth is flat requires the additional conviction that we’re all being deliberately lied to, not only by NASA who, it’s claimed, staged the moon landing, but by potentially every single government, scientific organization, and legitimate astrophysicist on the planet. So, Flat Earthers fall well within the larger bounds of conspiracy thinking.

While a lot has been written about the origins and cognitive biases that underlie conspiracy thinking, there has been much less research on how to effectively change such beliefs. There is evidence that fringe beliefs can be strengthened by group affiliation, which these days is especially easy to achieve online where conspiracy theories are fueled by “cognitive bias on steroids.” And from research on correcting misinformation (not conspiracy thinking per se), we know that mainstream discussion, and refutation from “official sources,” can lend legitimacy to conspiracy thinking rather than having a dampening effect, resulting in greater “group polarization” through the so-called “back-fire effect” (though the strength of this effect has been called into question in recent research).

On an individual level, successfully modifying belief systems usually requires interacting with people who hold different beliefs, so long as the goal of that interaction isn’t debate. In other words, changing “hearts and minds” shouldn’t be about arguing and trying to convince the other side. That doesn’t work in social interaction and it doesn’t work clinically in psychotherapy. Instead, discussions should start with empathic listening and validation of some of the core premises that underlie conspiratorial thinking. For example, we might agree that accepting everything we’re taught in school at face value isn’t necessarily the best way to learn the truth. From there, working together to assess evidence while considering other perspectives and alternative explanations as we do in cognitive behavioral therapy can soften the intensity of beliefs. From a clinical perspective, it’s that intensity, rather than the content of the belief, that most often gets us into trouble by influencing our actions in potentially harmful ways and should therefore be the target of interventions.

► Is there some sort of connection between the rejection of mainstream science and conspiratorial thinking?

Conspiracy theories by definition involve rejecting conventional facts and evidence. Sometimes that’s related to science (as with Flat Earthers) and sometimes not (as with moon landing conspiracy theorists). What’s interesting is that conspiracy thinking isn’t associated with lack of education and conspiracy theorists often think of themselves as skeptics in the proper scientific sense of the word. But in practice, they often employ the opposite of the scientific method, starting with an intuition and then sifting through information to confirm it and rejecting scientific consensus in the process. We’re all susceptible to that kind of confirmation bias, but this way of seeking the truth isn’t science or skepticism, its denialism and pseudoscience.

We know that despite what we imagine, normal people often don’t think very rationally. The scientific method is a validated way of bypassing personal biases in the search for facts. This suggests that enhancing basic science education starting in elementary school might very well be a long-term approach to reducing conspiracy thinking, particularly when that thinking runs contrary to scientific facts.

For more on Flat Earthers, see my other blog posts:

► Flat Earthers: Belief, Skepticism, and Denialism

► Behind the Curve: The Science Fiction of Flat Earthers

► Flat Earthers Redux: Subjective Belief, Science, and Reality