Race and Ethnicity

Race, Amplified?

How what you look like affects when and how you’re stereotyped.

Posted May 1, 2019

Take a look at these pictures, both of Asian-American women. Who would you guess is better at math?

If you’re like most people in our recent research, you chose the woman on the right, although perhaps without knowing why.

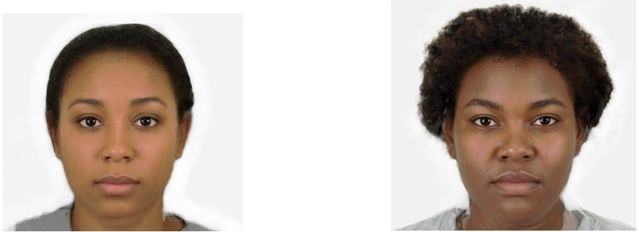

The next set shows African-American women. What does your gut say now?

This time I’d bet that you tagged the woman on the left as more likely to be the math whiz. Why? The answer does have to do with race—but maybe not in the way you’d expect.

We’re used to thinking about racial groups as something a person belongs to, or not. Do you check the box for Asian? Black? Latino/a? Or Native American? If so, that makes you part of a minority group in the U.S. context. And most people agree that belonging to one of these groups makes a person more vulnerable to others’ negative stereotypes.

But there’s more to it than that. Within each racial group, as we’ll see, not everyone’s experiences with stereotyping and discrimination are the same. One key factor? What they look like.

The concept we’re talking about has many names in science and in literature. In our research, my colleagues and I refer to racial phenotypic stereotypicality; more simply, it’s the degree to which a person looks like a “typical” member of his or her racial group. Among Black Americans, a person higher on racial phenotypic stereotypicality might have darker skin or a broader nose, compared to other Black Americans. Among East Asian Americans, “typical” features include darker hair, rounder cheeks, or more almond-shaped eyes. And among Whites, those with blue eyes and lighter hair are seen as “more White” than others.

The idea is that within a racial group, people vary in how much their physical features match the prototype. And those who look more typical are likely to have more severe experiences with stereotyping and discrimination than their peers who share the same heritage—but who have a less-typical appearance. Evidence from all corners backs this up.

In a recent project, my colleagues and I tracked a group of minority college freshmen who sought to major in STEM (science, tech, engineering, or math). Persistence in the major is a substantial problem in STEM education. As many of half of STEM-interested freshmen leave the major before they graduate, and rates are worse among students from minority backgrounds. The result is a national workforce that’s undertrained in STEM skills.

We followed the students in our dataset to see who would still be in STEM at graduation, and who would drop out. We wondered: Would STEM persistence vary within each racial group, depending on how students look?

It did. Students from underrepresented groups (here, Black, Latino/a, and Native American students) were less likely to stick with STEM if they looked more typical of their racial group. In contrast, Asian-American students whose appearance was more typical were more likely to persist in STEM, compared to Asians with a less-typical appearance.

We think this happens because of the experiences students have in the STEM classroom. Do they get a welcoming vibe or a side-eye? Do they get the feeling that others expect them to succeed, or assume they will fail?

Follow-up experiments gave us a clue. We showed study participants pictures like the ones above. Each pair of pics was of the same race, gender, and age, and rated as similarly attractive, but different in the typicality of their appearance. Repeatedly, our participants declared that the “more Asian” woman—but the “less Black” woman—had stronger STEM skills than her same-race counterpart. Distressingly, even academic advisors—those whose profession involves recommending course paths to college students—showed this vulnerability in our studies. (And I have no doubt that professors would do the same.)

In sum: We all stereotype within racial groups, not just between them. A person may assume not only that Asian Americans are more STEM-skilled than Black Americans, but also that the more Asian—or the less Black—someone looks, the more she has what it takes to succeed. It’s plausible that professors, advisors, and others signal these damaging stereotypes to the very students they seek to hold on to in the classroom. Students pick up on cues that they’re not welcome, eventually dooming their ability to see themselves as capable in a competitive STEM environment.

African Americans have long grappled with an awareness that some in their community have “the look” seen as necessary to compel change. It’s a new idea, though, to many in the majority. Most White Americans appear unaware of their tendency to evaluate minorities differently based on appearance—that is, that they stereotype within racial groups.

Our goal is to bring this phenomenon to light, as a first step. Wiping out race as a factor in college and workplace settings, both in and out of STEM, means acknowledging that discrimination rears its head in many guises. These views may be unconscious, but they’re no less lethal to our nation’s vision of a strong and diverse STEM workforce.

This is an evidence-based blog. Check out the references for more information, and to form your own opinion. Sources behind paywalls may be findable via Google or by directly contacting an author.

References

Blair, I. V., Judd, C. M., & Fallman, J. L. (2004). The automaticity of race and Afrocentric facial features in social judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(6), 763-778.

Eberhardt, J. L., Davies, P. G., Purdie-Vaughns, V. J., & Johnson, S. L. (2006). Looking deathworthy: Perceived stereotypicality of Black defendants predicts capital sentencing outcomes. Psychological Science, 17(5), 365-453.

Hebl, M. R., Williams, M. J., Sundermann, J., Kell, H., Davies, P. G. (2012). Selectively friending: Racial stereotypicality and social rejection. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48, 1329-1335.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2015). STEM attrition: College students’ paths into and out of STEM fields. Washington, D.C.

Williams, M. J., George-Jones, J., & Hebl, M. R. (2019). The face of STEM: Racial phenotypic stereotypicality predicts STEM persistence by – and ability attributions about – students of color. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 116(3), 416-443.