Perfectionism

Are You a Perfectionist?

Perfectionistic behaviors often aren't about actually being perfect.

Posted November 4, 2019

I've lived, well, let's just say a lot of years. More than 21. And it's only been recently that I've discovered that I am a secret perfectionist. Secret from me, that is.

It was amazing to me to realize that. I always thought of myself as so far from perfectionism that it was like the difference between, well, right and wrong. I didn't even consider the idea as relevant. Hmm. But it turns out I had more perfectionistic traits than I ever imagined.

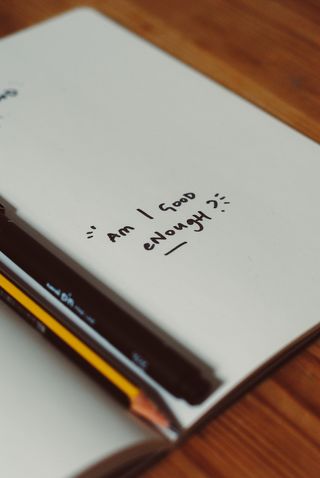

Perfectionism can be a positive or a negative trait. When it's negative, the person tends to be motivated by fear of failure or an effort to avoid difficult feedback or unpleasant experiences. When you have a high fear of failure, you see yourself as not good enough.

Perfectionists strain compulsively toward being good enough. In their minds, it's about being accepted by others and being good enough not to be rejected. Perfectionism is a social issue in many ways because it's about others' reactions or imagined reactions to you or the comparison with others.

Being good enough often means not having any flaws or making mistakes. Somehow in the perfectionistic mind, being accepted means meeting a very high, extremely high bar. Performance and public interactions become about social comparisons.

Did someone else look more together than you? Did someone else get more praise than you? Does someone else have a newer, fancier, more expensive car than you? Or perhaps a more environmentally friendly auto?

In perfectionism, self-worth comes from achievement and "wins." When you don't "win," you judge yourself so harshly that you don't want to try anymore. It's painful to think you're "not good enough," and the fear of rejection, the sense of rejection, can be incapacitating, even when it's not factual. Imagining that you are being shunned, kicked out of the tribe, for not being good enough can be crushing. You can easily begin to hate yourself.

That sense of not belonging goes deep, back to our tribal roots, where we couldn't survive if we were ostracized by the tribe. The fear of being rejected by the tribe can lead to avoiding social situations. Perfectionists can be quite lonely.

How does perfectionism show up in social situations in everyday life? Maybe your best friend invites you to dinner with a group of friends she has that you don’t know. She wants you to meet them. Are you excited and expecting to have new connections? Perfectionism can sneak in to make you worry about whether they will accept you or not.

You worry about not knowing what to say or even what to wear. You don’t know what their interests are, so you can’t plan what to say. You can’t control how the evening is going to go, so you begin to think of how you can get out of the event.

Or you go but freeze. You nod and answer questions, but you don’t really let people know who you are. That just confirms your worse fears—you believe even more strongly that you are flawed. You try to plan even more for the next event, try to do better—which makes it scarier.

That brings up another component of perfectionism. The need for control. You want to plan conversations, control where events occur, control who is present, plan the activities of the evening. Spontaneity or just letting the evening flow is scary. How can you be sure you’re acceptable, and your flaws aren’t obvious if you don’t have control?

See how perfectionism can sneak in, and you aren’t even aware of it? Part of letting go of perfectionism is letting go of control. If you have a chipped plate, so be it. If there are two extra people coming, that’s great.

If your main dish is overcooked, well, the most important part of the evening is not that you’re a good cook, right? It’s about having a good time with people. Changing the focus from your performance and how others might judge you to one of enjoying the company of others and contributing to the group can make a difference.