Philosophy

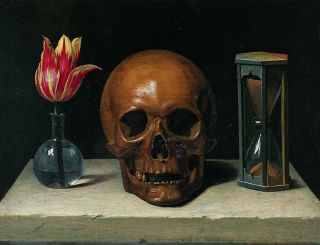

Remember, Thou Art Dust

Here's how philosophy teaches us to contend with death.

Posted September 27, 2023 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- Death is a fundamental part of human existence, and yet we rarely think about it.

- Avoidance and repression increase death anxiety rather than alleviating it.

- Philosophy teaches us to contend with our own mortality and the frailty of human life.

- Doing so increases our empathy for others and our understanding of ourselves.

Imagine a client comes to your therapy office wanting to discuss feelings of despair. He has been given a short time to live and, looking back on his life, feels that although he has accomplished much in the eyes of the world, he has little to show for it. Wealth, stature, the esteem of friends and colleagues—all this seems hollow in the face of his impending death. He’s troubled by questions of meaning and wants to know what his life has been for.

This is no mere thought experiment. It is, instead, a brief summary of the pretext that led Boethius to write The Consolation of Philosophy, one of the most important works in the Western intellectual tradition.

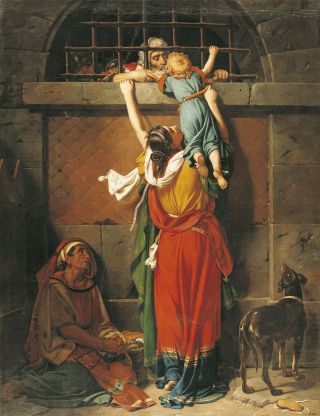

Before being sent into exile to await his eventual execution, Boethius had been a statesman, a philosopher, and one of the most highly educated and respected individuals living during the final days of the Roman Empire. Sentenced to death by King Theodoric, he found himself confronted with problems as relevant today as they were in 523 when he recorded them from his captivity.

At some point, every therapist will see a client wrestling with the questions that arise from the awareness of death. What is the meaning of an individual life? What survives us when we’re gone? Why do bad things happen to good people while the malicious seem to flourish? Is there any sense to be made from suffering? And if not, how are we supposed to bear it?

Contemplating mortality is a fundamental part of human existence. And yet, as Boethius notes, society seems to be structured in such a way that we rarely, if ever, think of it.

Consider the number of songs that include some formulation of the phrase “I’m going to live forever” or the noticeable trend—particularly pronounced in recent years—of actors, politicians, athletes, and other cultural leaders refusing to acknowledge the effects of time and insisting upon staying in the limelight. Think of our society’s obsession with youth and beauty, health and hygiene, or the ways we fetishize medical and technological advances.

These “shadows of happiness,” as Boethius calls them, are not bad in and of themselves. They become destructive, however, when we allow them to distract us from the reality of the human condition. We are mortal, and, as difficult as it is to admit, pretending that we can live forever by refusing to acknowledge the impermanence of our lives does nothing to change that fact.

What, then, can be done? Since the time of Socrates, philosophers have insisted that life is better when lived in light of death. Indeed, Plato goes so far as to call philosophy “practice for dying and death” and teaches his disciples that it is far worse to commit the known evil of injustice than to enter the unknown that awaits us in the grave.

For Boethius, contemplation brings consolation. Mortality robs the things of this world—“wealth, position, power, fame, pleasure”—of their glint, and when we are mindful of it, the awareness of death helps us to put things in their proper places. We will never learn to seek, let alone find, our “true happiness,” Boethius writes, until we have let go of the many false goods that divert our attention from the quest. An unexpected prognosis or the sudden loss of a loved one can act as the catalyst to begin the search, but we don’t need to wait for that. The truth of our condition is available at every moment.

Psychologists such as Ernest Becker and Rollo May have long recognized the import of philosophy when contending with death. The existential and psychoanalytic traditions teach adherents to draw from philosophical discourse, especially when wrestling with this most difficult of topics.

And yet, how can one counsel or console those who seem to be confronted with these questions when it is already too late? What can be offered to the client described at the start of this piece?

As the example of Boethius reminds us, contemplating the limits of our existence can be beneficial even up until the moment of one’s dying breath. For, “Good fortune deceives, but bad fortune enlightens,” and enlightenment is no small thing. It is, rather, a supreme form of consolation, especially when it enables one to admit a truth that has been repressed or resisted.

A beautiful illustration of this can be found in Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilyich. So long as the novella’s eponymous protagonist refuses to acknowledge that he is dying, he remains paralyzed, trapped in a web of anxiety and despair. It is only when he comes to terms with his own mortality that he is able to walk through his fears, assess his life honestly, and seek forgiveness from those he has wronged.

Similarly, philosophy—as a practice for dying and death—can help us to be more present to the suffering of others by making us more honest with ourselves. Memento mori, as the Medievals used to say. Remember that you will die. Or as Gerasim—the only character willing to care for the dying Ivan Ilyich—says near the novella’s conclusion: “We’ll all die. Why not take the trouble?”

References

Boethius. (1999). The Consolation of Philosophy. Trans. Victor Watts. New York, NY: Penguin.

Plato. (2002). Five Dialogues: Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, Meno, Phaedo. Trans. GMA Grube. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing.

Tolstoy. I. (2012). The Death of Ivan Ilyich. Trans. Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. New York, NY: Vintage.