Psychology

Psychology's WEIRD Problem

Often, WEIRD scientists conduct WEIRD experiments that are not generalizable.

Posted April 15, 2020 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

In 2010, psychologists and behavioral scientists had a revolutionary realization: All humans are not the same as the North American college students. Earlier, the assumption was that human beings share fundamental cognitions, behaviors, biologies, and emotions, so why study others? For example, one might assume that how our pupils dilate might not be too different across the world. However, this is apparently not true. A study comparing European and Moken children (from the islands of Asia's Andaman Sea) found that the former, when underwater, widen their pupils, while the latter constrict them to improve vision. Thus, apparently European children, because they do not usually need to see properly underwater, have blurry eyes when they are underwater. Moken children, who live a semi-nomadic life based on the sea, however, need to visually focus to perform underwater tasks, such as foraging food. So, apparently, cultural experiences even change your biology.

Let’s consider another example: running. Certain pockets of the world over-rely on running shoes, which are often cushioned; others run barefoot. Studies have shown that runners who use running shoes land differently than those who run barefoot. This begs the question: If even low-level functioning like visual processing, or the evolution of the human foot, is so different because of cultural differences, how can we claim that psychology, or behavioural science in general based on studying a handful of people, is applicable to everyone around the world? How can psychology call itself the science of human behaviour if it studies only a select few?

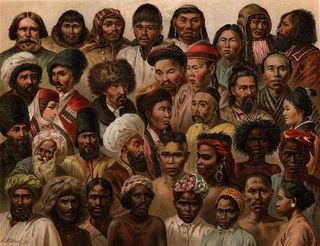

The realization that not everyone is the same, and that culture could change the most basic of human biology has not changed much since 2010, however. A significant number of participants in behavioral science experiments continue to represent the Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) society, which covers only about 5% of the human population. For instance, in the top six APA journals, 68% of the samples studied are drawn from the United States, and 96% from WEIRD countries. You might think, OK, these journals are general and cover topics that are thought to be universal. How about fields like evolutionary and cross-cultural psychology, which explicitly depend on heterogeneity in the sample studied? Turns out, they are not doing things very differently: In the 893 articles published in 2015 and 2016 in the top five cross-cultural psychology journals, a staggering 96.7% participants were WEIRD, and more than 85% were American. In 2012, in Evolution and Human Behavior, the official journal of the Human Behavior and Evolution Society, 65% of the sample used was WEIRD. In the 180 papers published in 2015 and 2016 in two of the evolutionary psychology’s leading journals (Evolutionary Psychology and Evolution & Human Behavior), 81% of the sample was from WEIRD countries, and 89% from developed countries; ancillarily, 44% was a student sample. How do researchers substantiate the extrapolation of findings from this small, almost homogenous subsample, and call it the science of “human” behavior?

This kind of saturation might have its roots in something even more troublesome. Behavioral researchers themselves are mostly from WEIRD countries. A recent study, for example, tells us that three ZIP codes in the United States account for more than 50% of the research published in top-five journals of economics. It is likely that these researchers then solicit participants from their own institutions, perhaps even their own departments. This could have interpretive biases because other cultures are then considered as outliers. For instance, what might be trite practices in most other cultures, such as initiation into adulthood, are often considered “exotic,” and hence may not be studied at all. Journal editors and reviewers might say that it is not of general interest, meaning that just because they do not see it happening in 12% of the human population, it is not “normal.” Thus, a comparatively homogenous group of researchers then study a comparatively homogenous group of behaviours, belying the multiplicity of human psychology.

The situation is not that bleak, however, and some changes are being made. For example, communities and organizations such as the Psychological Science Accelerator, the Society for the Improvement of Psychological Science (SIPS), and the Institute for Globally Distributed Open Research and Education (IGDORE) are in the process of developing systems to collaborate with researchers across the globe. For instance, projects such as the Many Labs and Many Babies series have worked toward collaborating with many different, geographically-widespread labs. Further, the Psychological Science Accelerator is working toward a buddy system through which labs from developing countries can collaborate with those in developed countries. Additionally, journals such as Psychological Science have addressed the problem of homogenous samples, but without specifying any action plans.

In the end, this is an issue of validity, and should be treated as such: After all, what is the point of a science that does not study the majority of the population?

This post was written by Arathy Puthillam, a research psychologist at Monk Prayogshala, India. Her research focuses on social, moral, and political psychology. She tweets @WallflowerBlack