Psychology

How Influencers Use the Psychology of Covert Content

The creative influencers that capture our feelings without our awareness.

Posted August 4, 2020 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

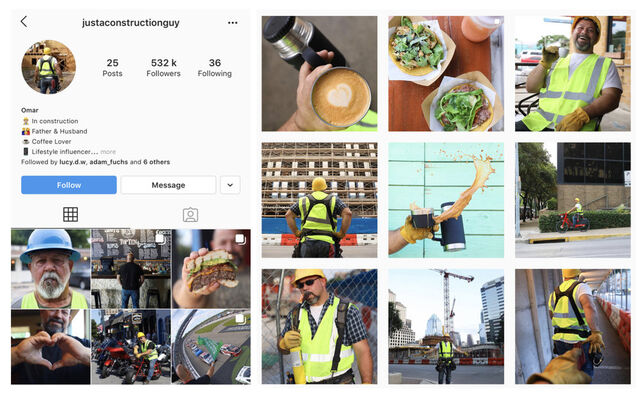

Burly, heavily bearded, and permanently decked out in construction gear, you might expect to see Omar holding a hammer, rather than an iPhone. And yet his Instagram is more active than the average high schooler. His pictures pop up with stunning frequency: on a construction site, drinking coffee, back on a construction site again.

In many ways, he’s the antithesis of a social media influencer. In one post, he details how he started his account just to playfully "compete" with his too-cool teenage daughter. He lists “lifestyle influencer” on his profile sarcastically. But to the tune of nearly 500,000 followers, Omar (@justaconstructionguy) is an Instagram sensation and another citizen in the world of micro-celebrities.

The only problem is that Omar, as the internet grew to know and love him, is a complete fabrication.

The account is the creation of Mike McKim, the owner of Austin's Cuvée Coffee. Together with Bandolier Media, they created “Omar” in the image of the brand — a blue-collar and hard-working anti-influencer. The man featured in the posts was compensated for the photoshoots but had no autonomy over the account itself. And while some of Omar's posts include other hashtags to poke fun at influencers, the creator brand @cuveecoffee is also specifically tagged in several posts on the page.

Ironically, he isn’t the self-professed antithesis of influencer marketing but rather the crystallization of it.

What to make of Omar? There’s a lot that can be said. Was he real in the sense that people thought he was real and found enjoyment in following his life? Was he real in the sense that he represented a real idea?

What is Omar? In a word, Omar is a strategy. He is a perfect embodiment of a new wave of creating, mining, and monetizing social influence. And he’s just the beginning.

Influencer Marketing: A Quick 2-Year History

To understand how we got to Omar, we have to go back in time to 2017 — eons ago in the breakneck pace of the influencer world. Influencer marketing was established and the number of micro-celebrities was growing quickly. All this growth brought attention from regulators. Many worried about its prospects when the Federal Trade Commission began watching influencers’ practices more carefully.

The FTC soon discovered that nearly 93% of influencers are not properly disclosing their endorsements, and in April, they started formally cracking down serving notifications to both brands and influencers.

When these regulations hit the fan, many thought this was the beginning of the end. In retrospect, it represented the beginning of a new era. With the FTC keeping a close watch, content that directly discusses the product or even uses it too easily could arouse suspicion. Now the influencers had an incentive to be sneaky, to give the brand exposure without looking like you’re trying to give the brand exposure.

If Jay-Z and Beyonce go on vacation and post a pic with a Corona bottle in the background of the shot, we may never know if it's a paid post or Corona just happened to be lucky enough to be in the vicinity and get free exposure. The content has the same effect on the FTC as it does on the masses. You can’t tell what’s real and what’s an ad.

The age of covert content was born.

The Science of Exposure

You might be asking yourself, well if the influencer isn’t actually promoting the product in their picture (hell, some seem like they don’t even know it’s there), how can this possibly be helpful to the brand? Here’s where the neuromarketing perspective comes in. Even if the influencer isn’t actively promoting the product, it still has a major impact.

In fact, the impact is actually enhanced, not hindered if we don’t think it’s an explicit ad. Marketing works best when you don’t know you are being marketed to.

This is the neuroscience of exposure. It all starts with familiarity: As a general rule, we humans like things that are familiar. If something is familiar to us, it means we’ve seen it before, which means it probably isn’t life-threatening. From the standpoint of evolution, non-life-threatening is unequivocally good.

Behavioral psychologists and neuroscientists call this the Mere Exposure Effect. All else being equal, the more we’re exposed to something, the more we like it. And fascinatingly, this preference for the familiar appears to operate completely outside your awareness.

In one experiment, researchers showed English speaking participants a range of different Chinese characters. No task, just look at them and pay attention. Later, participants were asked to guess what each character meant. Remember, the participants knew zero Chinese. From their perspective, they were just guessing random words — “dog,” “cup,” “handsome,” “soccer.”

Here’s the thing, the guesses weren’t random. If they had seen the character before, even briefly, they were much more likely to assume the word was associated with something positive like “Happiness” and “Love,” despite not having any idea what they actually meant. These results persisted despite the fact that none of the participants remembered having seen the characters before.

Over 200 studies across a wide array of domains have replicated the mere exposure effect finding — you like things the more you’re exposed to them. Similar findings have been noted in animals as well, and even in developing chicks still in the egg. Tones of two different frequencies were played to two groups of fertile chicken eggs. At birth, the chicks preferred the tone they had previously heard.

And here’s the kicker. Research has found that the effect is more pronounced when the exposure is implicit. If we don’t consciously know we’re seeing an ad for Corona but it appears in the background of a few posts we’ve come across, we like it even more! This has massive implications for consumer psychology and ultimately, your behavior.

Exposure is even more potent when you don’t consciously know you are being exposed to a product.

Think about it. When you know a commercial is, well, a commercial, the message loses power. You know you are being sold to and it feels inauthentic. We shut down our openness and turn on our critical thinking, which is kryptonite to the advertising brand.

The era of social influencers has converged on this feature organically, perhaps by accident. Micro celebrities and influencers capitalize on the brain’s preference for integrated, subtle exposure. As YouTube Influencer Anwar Jiwabi recently told Forbes, “If the content isn’t funny, or if it feels like a 100% scripted ad, then viewers aren’t going to pick that up. I did a video with Steph Curry, for Brita, and it was very organic and fun. In my mind, I’m creating a regular video with a product instead of creating an ad.”

From the perspective of influencers, covert content is a win-win. It is an optimal tactic for delivering value to brands (who pay them) without attracting unwanted attention from regulators. And with each new creative, integrated piece of content, the line between “organic” content and branded content continues to blur along with an objective way to regulate it.

The Arms Race of Covert Content

Social media has galvanized digital marketing like no other medium before it, no surprise here. The influencer branch of the social media tree has further obscured the lines between advertising and organic content and this is why the sway of influencers goes well beyond direct endorsements. In fact, the less direct an endorsement, the more influential it could be. Driven, perhaps ironically, by regulation, the industry is becoming more covert, and in turn, more effective.

Some of the best marketing is done without us ever knowing we’re being marketed to. And in fact, it’s effective because we don’t know we’re being marketed to. With a renewed focus on covert content, the influencer economy has continued to grow and is expected to be a $15B industry by 2022. And if more personalized, face marketing techniques are adopted, these trends may even accelerate.

But users aren’t just passively taking this in. They’re starting to wise up to these tactics. You can only see the “bathroom selfie with a branded shampoo in the background” so many times before you become a little suspicious. So as consumers catch on, influencers are having to become more and more creative about integrating their content in a covert way that still feels authentic.

The neuromarketing arms race is on: An escalating battle between the awareness of the consumer and the creativity of the influencer.

Omar and his "love of coffee" is just the start.

This post originally appeared on the consumer behavior blog MJISME

References

Adweek: Influencer Marketing in 2018: Becoming an Efficient Marketplace, Giordano Contestabile

Bornstein, R. F. (1989). Exposure and affect: Overview and meta-analysis of research, 1968-1987. Psychological Bulletin, 106, 265-289.

Federal Trade Commission: FTC Staff Reminds Influencers and Brands to Clearly Disclose Relationship

Ward, Tom (2019) Forbes: The Influencer Marketing Trends That Will Explode in 2019

MediaKix (2019) 93% of Top Celebrity Social Media Endorsements Violate FTC Guidelines

Zajonc, R.B. (2001). "Mere Exposure: A Gateway to the Subliminal". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 10 (6): 224.

Zajonc, Robert B. (1968). "Attitudinal Effects Of Mere Exposure". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 9 (2, Pt.2): 1–27. doi:10.1037/h0025848. ISSN 1939-1315.