Sex

Curb Your Disgust

Disgust evolved to protect against contamination, but beware its moral effects.

Posted March 24, 2020

With a War-of-the-Worlds-proportion panic washing over the country, many are wondering what the next few months will look like in terms of basic daily life. As a disgust researcher, I have been hyper-aware of the increased aversions readily on display. Disgust, however, is both a helpful system and one we need to keep an eye on.

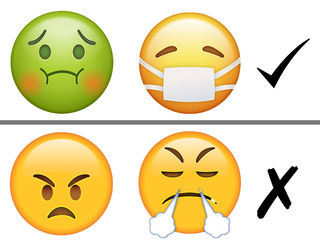

Disgust is an emotion that evolved to regulate how humans make decisions in the domains of consumption, steering us clear of foods harboring toxins and micro-organisms; contact, steering us clear of individuals displaying signs of infection; and coitus, steering us clear from individuals judged to be biologically unfit partners, such as family members and farm animals. If disgust only affected eating, touching, and sex, there might not be much to discuss. Cues to an epidemic would be limited to shifts in personal decisions to change one's diet, wear gloves, and disengage from Tinder for the month. But disgust infiltrates moral judgments, and in this domain, there is much to be concerned about.

Disgust seeps into moral judgments in three ways—three avenues of subversion we need to protect against, especially now. First, personal feelings of disgust pattern the moral norms and laws we support. For instance, the activation of personal aversions toward sex with one's own siblings predicts moral disapproval of sibling incest for everyone.

Beyond incest, personally held judgments can fuel norms that condemn the behavior of others, thereby leading to, in some cases, moral bonfires that invariably target a particular group of individuals. From this perspective, heterosexual men's views on gay sex have led to draconic laws against homosexuality. So we need to be careful about how our personal sense of disgust influences our desires to initiate rules condemning particular groups.

Second, disgust can be used to identify the moral leanings of others. When leaders, neighbors, or co-workers use the rhetoric of disgust, we get a sense of what rules they'd back and the groups they view, consciously or not, as exploitable. A quick perusal of President Trump's comments in which he uses disgust provides a laundry list of groups he condemns. And once disgust is in the mainstream, those views can become favored, leading to support for taxing people who buy large sodas or who drive gas guzzlers. Or more distasteful, disgust-motivated rules may even become enforced, such as occurred in Nazi Germany or the Jim Crow South.

Perceptions of widely held beliefs—whether felt or not—lead more people to hop on the disgust bandwagon. This is because, third and last, disgust language can be used as a shield against condemnation. When someone utters that a group of people or an act is disgusting, it signals two things: 1) that they would back rules condemning "this group" or forbidding "that act"; and, 2) that they themselves do not fall into the category of people to target. In this way, disgust communicates, "Take your condemnation sights off me. I'm one of the 'good' people—let's go after 'them.'"

As the coronavirus spreads, we need to be vigilant about these very different types of disgust. Personal disgust can help us protect against infection. Moral disgust, however, is nefarious and serves to target and condemn. Majority groups can dangerously leverage the power of disgust to serve their own ends.

When you hear disgust language, think of it as a thermometer, taking people's temperature on their interest in joining an alliance that might further coordinate to curb the freedom of, impose taxes on, socially exclude, or even exterminate another group. And when everyone speaks with disgust about a group, it can be dangerous to disagree. As Nazi Germany showed us, moral disgust can operate as a powerful tool, causing conformity. So, as people become ill around us, we can and indeed must push back on our primal instincts to use disgust to fuel our social and moral judgments.