Cognition

What is Justice?

What has inspired me to study justice for 20-some years.

Posted July 10, 2019

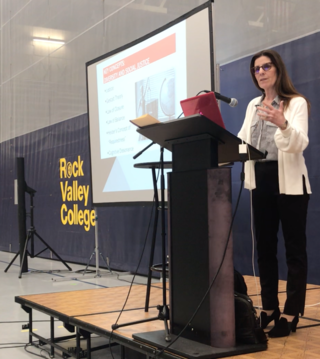

At a recent keynote speech at Rock Valley College — its David H. Caskey Memorial Lecture — I had the opportunity to talk about what justice is; who I am to be talking about it; and who I am to be talking about the interpersonal aspects of justice and its transgenerational impact.

The talk that night was research-oriented. But what has inspired me to study this subject for 20-some years is my own personal background and how justice has impacted me — or, more accurately, how injustice has impacted me.

Both of my parents were survivors of concentration camps and so I grew up with a keen sense of what injustice means. It wasn't just a theoretical concept. Both sides of my family were killed, so I grew up with no extended family. I was always deeply interested in the question, "How could human beings do this?"

And I think my legacy is a big one maybe, but I think many people can relate to what it feels like to be treated unfairly — even interpersonally, sometimes we feel we've been wronged, so I bring it down to that level as well. It doesn't have to be a huge historical event. At the end of the evening, I also talked about our country and how resentment is very much a part, in my view, of polarization in the United States today.

So, what is justice?

Humans have an inborn sense of injustice — literally inborn.

Our sense of ought is similar to our sense of beauty.

There are religious traditions that offer moral exemplars: Should we punish those who act unjustly? How should we feel when someone harms us?

Different societies may come up with different definitions of what justice means, so, for example, maybe in some Middle Eastern countries if you steal something your hand will be cut off, and we might not agree with that. But Charles Darwin proposed that all of us have an inborn sense of ought. Something ought to happen or something ought not to have happened and all human beings have this underlying mechanism of judging right and wrong.

Fritz Heider, a famous name in psychology who was a pioneer of social cognition and attribution theory, actually took Darwin's idea of ought and applied it to social psychology (although he didn't credit Darwin) and he developed what's called the psychology of interpersonal relations.

Our sense of ought, he said — and this is interesting — is similar to our perceptual organization.

[See the slides at left which illustrate the sense that, perceptually, human beings like to have consistency and balance.]

Copyright © Mona Sue Weissmark All Rights Reserved

Watch the videos here: Behind the Research and The Origins of Justice.

References

Weissmark, M. (forthcoming 2019). The Science of Diversity. Oxford University Press, USA.

Weissmark, M. (2004). Justice Matters: Legacies of the Holocaust and World War II. Oxford University Press, USA.

Weissmark, M. & Giacomo, D. (1998). Doing Psychotherapy Effectively. University of Chicago Press, USA.