Motivation

Overcoming the March Motivational Slump

Behavioral science strategies for recharging how you set and pursue your goals.

Posted March 3, 2021

By Emily Balcetis and Dennis Aronov

It’s already March of 2021. Are you still doing your favorite Chloe Ting 2-week shred? Are you still trying to increase how much you save, read, lift weights, check in with your therapist, or whatever is a popular goal where you live? Likely not. As we move farther from the start of the new year, the odds that we have stuck to these and the other resolutions we might have set drop rapidly. Researchers at the University of Scranton found that compared to one week into the new year, the percentage of people who stuck to their resolutions dropped by half by the end of March.

But there are concrete strategies we can use to up the chances we stay in the zone, committed to working on those goals we set for ourselves. The just-released book, Clearer, Closer, Better: How Successful People See the World, takes a behind-the-scenes look at some amazing people who illustrate the scientific principles of setting, inspiring, and maintaining motivation.

Here are some of the tactics that work. And, bonus: All the strategies offered cost nothing, are available to everyone, and repurpose a sort of superpower that we already have at our disposal: the power of sight. We can teach ourselves to see our options, progress, and prospects differently to increase our odds of success.

Become Your Own Accountant

Collect data on yourself and review your portfolio routinely. If you were trading stocks, you would take note of the rise and fall of your shares’ values. You would use these objective numbers to inform your decisions about whether to buy or sell. Take the same approach to decide whether to invest more in your own personal goals.

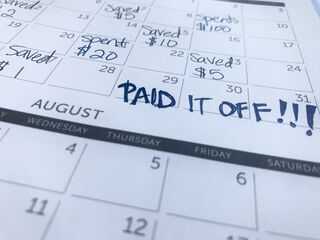

Consider the case of Carrie Smith Nicholson, a 25-year old former small business accountant who recently found herself in a financial predicament she’d never expected. Recently divorced, Nicholson was saddled with credit card and auto loan debts that she herself was responsible for managing. The total amounted to a third of her salary at the time.

She had set her sights on financial freedom, and in 14 months paid off her $14,000 debt entirely. How? She became her own personal accountant. Nicholson used an online payment-plan calculator that created a timeline and displayed a chart of past progress and a balance that moved closer and closer to zero. It showed her credit score as it increased along the spectrum from red to green.

Nicholson’s approach used a tool to visualize, monitor, and celebrate progress. It was a perceptual aid that fostered self-assurance but also provided real-time and importantly accurate feedback about the actual state of affairs. There is a problem we all face, and that’s that the harder we want to make a goal come to fruition, the more our own memories work against us when we try to track our own progress, research finds. To combat our faulty memories, we can collect and analyze real data on our own efforts and trajectory.

Assume a Narrow Focus

We can find ourselves distracted by new opportunities and those can take us off course of a primary goal of interest. Keeping our eyes on the prize, in both a metaphoric and literal sense, can give us the boost of motivation we need to push through to the end.

Take this example. Dutch students played a tedious word game, but they could win money for pushing through the monotony. The more questions they got right and the faster they played, the more money they could make, and the researchers measured how quickly the students moved through the different stages of the game. The researchers tested to see if focusing the students’ attention on how much they had left to go before the game was over would encourage them to work faster. To track progress, the screen presented a progress bar filled with dots. With each word game the students finished, a dot disappeared. This visual narrowed players’ focus on what remained to be completed because when all the dots were gone, the game was over. Players who narrowly tracked what remained until the goal was met worked faster and better, and as a result, made more money.

But this tactic backfired when the students were just starting out. If they narrowly focused on the end state too early, their pace slowed, they made more mistakes, and they left with their wallet a little thinner than it otherwise could have been.

You don’t have to be Dutch or a student to reap the benefits of narrowly focusing when you need an extra push to get through. Here’s another example. In my research lab, we surveyed hundreds of people competing in three different New York Road Runners races. On average, these runners held steady at an eight-and-a-half-minute mile and logged about 18 miles per week in training, so they were capable of finishing the four, six, or nine-mile race they were about to compete in. They told us about the different ways that they focus their attention at different points of a race. We found that these seasoned athletes changed their strategies depending on whether they are just starting out or nearing the end. In the last half-mile, almost 60% narrowed the focus of their attention more often than they expanded it. Using that narrowed focus strategically was key to their success.

See the Big Picture

In contrast to focusing narrowly, sometimes we need to take a step back and see the big picture with a wider frame. Big picture thinking can encourage decisions that better align with our long-term objectives, and help us avoid temptations that seem great now but which we’ll regret later on. Specifically, it can help us better manage our time.

Research supports this claim. Over 35 years ago, a team of academic advisors met with college students every week for almost three months during the first few semesters to teach study skills. Together, they created flowcharts of what they would need to accomplish, where and when they would work on their tasks, what they would need to achieve to feel good about themselves, and how they would reward themselves. But only some of the students assumed a wide bracket. These students broke their flowcharts down into weekly blocks and set milestones for each month. Other students assumed a narrow focus. They set milestones, but the deadline for accomplishing these targets was the end of each day.

Planning, tracking, and materializing improved outcomes for these students academically. Both groups were less likely to have dropped out of college a year later than students who had not participated in the program. But students who learned to plan using a wide bracket earned much better grades than students who learned to plan using a narrow focus. In fact, assuming a wide bracket led to nearly a full-letter-grade advantage: The monthly planners had on average a 3.3 grade point average while daily planners had a 2.4, which was essentially the same as for students who had not made plans at all.

Finding Your Fresh Starts

If you’ve faltered with the goals you’ve set, you can always start fresh. New Year’s is a common point in the calendar when people double down on renewing their commitment to self-improvement. But January 1st is no more magical a start date than the start of next month. In fact, researchers have found that Google searches for the term “diet” (Study 1), gym visits (Study 2), and commitments to pursue goals (Study 3) all increase following temporal landmarks, important moments in time like a birthday, a special holiday, and even the start of new weeks. Simply looking at your calendar and deciding what day is special to you can serve as a fresh starting line that creates a new mental accounting period. You can pick your own start date, be it January 1, St. Patrick’s Day, or even just the next Monday. The point is that you can imbue that date with meaning and relegate and past missteps in the pursuit of your goal to the past and start anew.

Filling Your Toolbox

It might seem like suggesting you use a narrow frame or a wide bracket is a contradiction. But it’s not. We need diversity in the tools we use because there are situations when one will work better than another. An artist’s palette includes more than one color of paint. A chef’s knife block includes more than just cleavers. A good wine cellar is stocked with more than just cabernet.

We can think of these strategies as different tools in a toolbox from which we select when working on a self-improvement project. Consider them a hammer, screwdriver, wrench, and pliers—pretty basic implements, but useful for almost every job. Sometimes the goals we set require us to use multiple strategies, just as any home repair may require more than one tool. The goal here was to offer you a guided tour of a home improvement store and point out some of the tools you might not have added to your own set.

Dennis Aronov is a research assistant in the New York University Social Perception Action and Motivation Lab.