Coronavirus Disease 2019

Death, the Meaning of Life, and Coronavirus

Meaning still resides in the wonder of small, everyday moments.

Posted March 19, 2020

Life is short. As Samuel Beckett wrote in Waiting for Godot: “They give birth astride of a grave, the light gleams an instant, then it’s night once more.” The best remedy is to resolve to make life choices that ensure that while the light still gleams, your remaining days, weeks, and years are worth it.

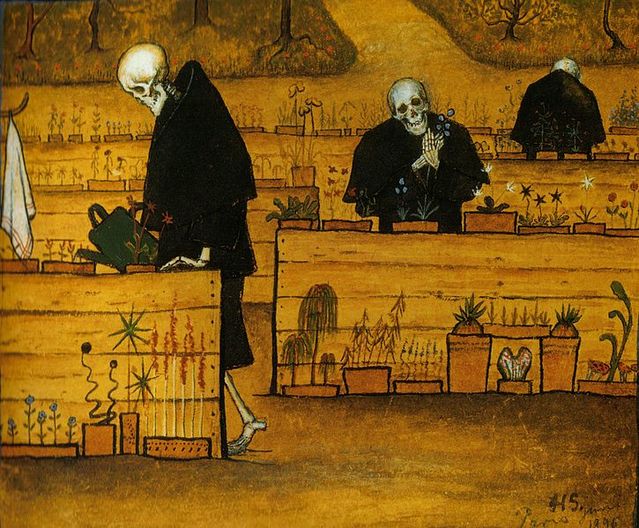

The above words are from my book, A Wonderful Life – Insights on Finding a Meaningful Existence, which comes out this week to a world quite different from the one in which it was written months ago. When writing it, gloomy thoughts about sickness, tragedy, and death seemed remote—something one had to remind oneself about. Memento mori—remember, you will die—has been the slogan of various ascetic and spiritual traditions throughout Western history.

I wrote how death, instead of being the ultimate meaning-nullifier, can actually imbue our lives with meaning. This is because we too easily let our lives happen to us. We dedicate more time in one evening to deliberate what film to watch than we do in a whole year to deliberating what would make our lives more meaningful, as philosopher Iddo Landau has pointedly noted. We do what others want us to do, we react to whatever requires our attention right now. Days, months, years pass by, without us ever stopping to think whether this is actually how I want to live my life. Life slides by while we do what is convenient, easy, and expected of us.

Death awakens us to the briefness and uniqueness of our existence. Given that I only have this one life to live, given that it can be taken from me any moment, why not live life fully? Why not make the best out of the limited time I’ve got? Why not choose to live according to my own terms, instead of letting someone else decide what I ought to do in life?

That’s why there are so many stories of people going through a tragedy—a life-threatening illness or losing a loved one—and emerging on the other side with a newfound clarity about what is truly important in life and what they want to do for the rest of their lives.

Right now, we don’t need to be reminded about the limitedness of our existence. The spreading epidemic has made everyone all too aware of how fragile the ordinary life can be. This is a tragedy on a global level, and the coming months will reveal how serious the consequences are and how will people and societies cope with this unprecedented situation.

While I don’t have anything unique to say about how to stay alive and safe during this crisis—wash your hands, engage in social distancing—I can help to make these days feel more meaningful. The recipe for meaningful existence, namely, is the same, whether you have days, months, or years to live.

Meaningfulness happens during living, not after it. Living takes place in the present, the present moment is all we have—and all we will have. Past is simply a compilation of memories we experience in the present. The future is the projection of hopes and predictions we make in the present. As philosopher Gregory Pappas puts it, “foresight, hindsight, and present observation are all done in the present for the present.” Here he follows America’s most important public intellectual from hundred years ago, philosopher John Dewey, who summarizes his recipe for meaningfulness as follows: “So act as to increase the meaning of present experience.”

Life is composed of temporal moments, some of which are more meaningful than others. And them not lasting forever doesn’t detract from their meaningfulness, as already Aristotle pointed out: “Moreover, the good will not be good to a greater degree by being eternal either, if in fact whiteness that lasts a long time will not be whiter than that which lasts only a day.”

No matter what your situation is or how much longer you have to live, what you can do is to make the present moment more meaningful. When your focus is on making this moment and this day more meaningful, instead of longing for some metaphysical truths to drop from the sky, you’ll soon realize that the most meaningful moments typically consist of a few simple ingredients.

One is connection with others. Being together is one of the most meaningful things for us—this is confirmed both by research and our everyday experience. The crisis offers us a chance to evaluate who are the truly meaningful people in our lives. If I have to be isolated from the rest of humankind, with whom do I want to be isolated? Now is the time to connect with those people—if not physically, then through phone calls, video calls, and other modern means that keep us physically distant but emotionally close.

Second is contributing. When I am making a meaningful contribution to the lives of others, this makes my own life feel more meaningful to me. Backed up by several research studies I and other researchers have conducted, we know that a great way to experience meaning is to help others—friends, neighbors, local community, the society. The present crisis offers abundant chances to help others. Many vulnerable citizens should avoid all public places and need help in getting food from the grocery store. Shop for them. Many artists, restaurant owners, and other small businesses face bankruptcy as they’ve lost all customers for the coming months. Support them.

Connecting with others is thus crucial for meaning. But it is as important to connect with yourself. This is done by seeking activities that you find personally interesting, valuable, and fulfilling. What makes you tick? What do you enjoy doing when nobody is judging? Use the quarantine to engage in those activities. Put the music on in the living room and dance like no one’s watching. Similarly, we experience meaning when we master something—when we get to put our unique mix of skills and abilities to full use. Now is the time to learn something you’ve always wanted to master, be it a musical instrument or a certain software. Being able to express oneself is part of a fully lived life, and such self-actualization can make our lives feel truly worth living.

Meaningfulness isn’t something remote or rare. It’s an experience that exists in many of our everyday moments in stronger or weaker form. As workers, as parents, as friends, as neighbors, as ourselves—we have the chance to experience tiny moments of meaning every single day if we just pay heed.

Life may end one day. Every other day, it doesn’t. During all those every other days, we have opportunities to appreciate beauty and cultivate meaning. Meaningfulness resides in the small wonders of our everyday life. The famous Zen teacher Alan W. Watts compares life to music. He notes that in music one doesn’t make the end of the composition the point of the composition. In playing a song, the one who plays it fastest doesn’t win. What is meaningful in music is not getting to the end but what happens during the moments when the music is played. Too often we approach life as a kind of project with a serious purpose at the end. We focus so much on getting to that end, be it success or whatever else, that we miss the whole point along the way. ”It was a musical thing, and you were supposed to sing or dance while the music was being played.”

One day the music will stop. What happens afterward, no one knows. But there’s no point in waiting for the silence. If you’re reading this, then the music is still playing for you. So go out and dance—alone or with friends through a video call.

Copyright Frank Martela

References

Aristotle. (2012). Nicomachean ethics (R. C. Bartlett & S. D. Collins, trans.). University of Chicago Press.

Beckett, Samuel. (1954). Waiting for Godot New York: Grove Press.

Dewey, J. (1922). Human nature and conduct. Henry Holt and Company.

Pappas, G. (2008). John Dewey’s ethics: democracy as experience. Indiana University Press.

Watts, Alan W. (2002). The Tao of Philosophy, edited transcripts. North Clarendon, VT: Tuttle Publishing,