Environment

Nature, Nurture, and Noise

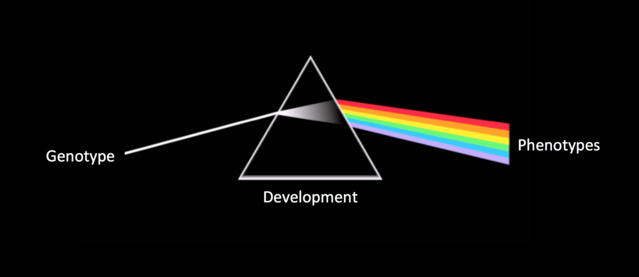

Why development is a crucial source of variation in innate traits.

Posted August 24, 2018 Reviewed by Devon Frye

When Francis Galton coined the term “nature versus nurture” in 1869, he crystallized a debate that had been raging for millennia about what makes us all the way we are. Are individuals intrinsically born with a particular palette of talents and tendencies, or are their psychological traits shaped instead by how they are brought up?

In modern times, “nature versus nurture” has morphed into “genes versus environment.” A more realistic formulation, rather than pitting the two forces against each other, allows for the joint or even interacting effects of “genes and environment” on our psychology. But whatever way you phrase it, this construction ignores a crucial third source of variation in our individual natures—development.

If differences between people’s natures were all due to them having different genes or growing up in different families and wider environments, then we should expect monozygotic (genetically identical) twins who are reared together to be extremely similar psychologically. But they are not. They are certainly much more similar to each other than pairs of dizygotic twins or regular siblings, who share only 50 percent of their genetic material—illustrating the important contribution of genetic variation to psychological traits—but they are still far from identical. There is some other source of variation at play.

One possible explanation for this is that we’re just not very good at measuring psychological traits. Unlike height, for example, which actually exists in the physical world, psychological traits like intelligence quotient (IQ) or Big Five personality measures are artificial statistical constructs. They simply let us rank people using an arbitrary scale, with inevitable fuzziness in the values. That fuzziness is certainly part of the answer, but those measures are at least consistent and reliable enough within individuals to doubt that it is the whole story.

Another possibility is that the unique experiences that individuals accumulate over their lifetime cause differences in their psychology, in addition to their genes and family environment. This sounds plausible, at first, and in a sense is obviously true—our experiences obviously affect our behavior. But the question is really whether such experiences cause a difference in the things we see as a person’s psychological traits. Twin and adoption research suggest not, or at least show that differences in the family environment contribute very little to differences in such traits. Monozygotic twins who are reared in different families are, on average, only slightly less similar to each other psychologically than ones who are reared together.

If a person’s experiences within their family environment don’t have much of an effect on their psychology, then why should experiences outside the home do so? There really isn’t any good argument why they should or evidence that they do. Decades of exhaustive searching have failed to find any such environmental factors or types of experiences that systematically affect our psychological traits. That is not to suggest that we don’t respond to our experiences at all or that we don’t develop characteristic behavioral adaptations to our surroundings. It is just that such adaptations seem to be layered on top of a set of more basal and more stable psychological dispositions.

What, then, is the additional source of variation in these basal traits? We don’t in fact have to look to the environment or to experience at all to explain this—much of it comes from inherent variability in how the brain develops.

The genome of any human encodes a program for making a human being, with a human brain, wired in such a way that mediates the core aspects of human nature. Genetic variation between people inevitably contributes to differences in the way our brains are wired and differences in our individual natures—this is why psychological traits are highly heritable. But even in two people with the exact same genome, the outcome of development would not be identical.

The genome is not a blueprint. It does not encode the precise outcome of development, because there is no way that it could. First of all, there is mathematically not enough information in the genome to specify every synapse on every neuron in the brain. But more fundamentally, the nature of the information in the genome is radically different from a blueprint. There is no plan—no vision of the outcome. All that is encoded is a series of mindless developmental algorithms that drive the self-organization of the embryo to result in an organism with certain characteristics.

Brains are not built, they’re grown, and growing things is a messy, unpredictable business. All of the biochemical processes and interactions underlying those developmental algorithms are intrinsically and essentially “noisy,” in engineering terms. The genome encodes information of which proteins to make in which cells, but the exact amounts produced are variable, and their subsequent interactions are subject to thermal fluctuations, random diffusion, and other emergent noise in cellular systems.

Any given genome therefore encodes not one specific outcome, but a range of possible outcomes, which will vary in all kinds of characteristics. Twins will thus differ in quantitative traits, with one being perhaps a little more intelligent, a little less neurotic, a little more shy, or cautious, or imaginative than the other. Moreover, due to the self-organizing nature of brain development—where small changes early on can be amplified through non-linear processes—this kind of intrinsic developmental variability can also lead to dichotomous outcomes in qualitative traits, such as being left- or right-handed, straight or gay, schizophrenic or not.

Development itself is thus a crucial third source of variation in our individual traits, in addition to genes and environment. Much of the non-genetic variation that people have inferred must be environmental in origin may instead be intrinsic to each individual. This means that many traits may be far more innate than genetic effects alone would suggest. It also places essential limits—in principle, not just in practice—on how accurate genetic predictions of such traits can ever be. In an era of stories about the rise of consumer eugenics, there may be some comfort in knowing that each of us represents the unique outcome of a set of intrinsically variable developmental processes that will never be repeated and could never be predicted.

Facebook image: Loza-koza/Shutterstock

LinkedIn image: Ollyy/Shutterstock