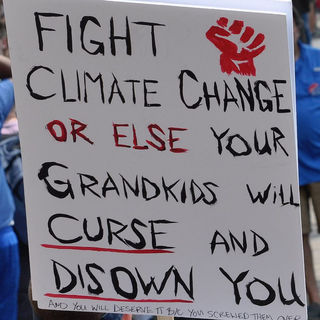

Environment

What Should We Believe About Climate Catastrophe?

Avoidable or inevitable? Should we prevent or adapt?

Posted September 9, 2019

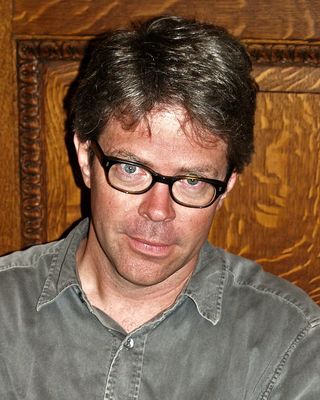

Jonathan Franzen—the prizewinning novelist perhaps most famous for snubbing Oprah—wrote a controversial essay in The New Yorker. It has been roundly criticized because it offers a disturbing take on the climate crisis. But the essay is more about the core concern of the post-fact era: whom do you trust?

Franzen’s style has been described as a “tonic of brutal honesty wrapped in stunning prose.” The second seems to make the first more palatable. His core point in The New Yorker is that it is a lie to assert (over and over) that the climate crisis can be averted if we act quickly; the evidence says it is too late and we must move to adaptation strategies rather than prevention.

“You can keep on hoping that catastrophe is preventable, and feel ever more frustrated or enraged by the world’s inaction. Or you can accept that disaster is coming.”

“Even at this late date, expressions of unrealistic hope continue to abound. Hardly a day seems to pass without my reading that it’s time to ‘roll up our sleeves’ and ‘save the planet’; that the problem of climate change can be ‘solved’ if we summon the collective will… The facts have changed, but somehow the message stays the same.”

The facts, according to Franzen, are that “If you’re younger than sixty, you have a good chance of witnessing the radical destabilization of life on earth—massive crop failures, apocalyptic fires, imploding economies, epic flooding, hundreds of millions of refugees fleeing regions made uninhabitable by extreme heat or permanent drought. If you’re under thirty, you’re all but guaranteed to witness it.”

But are those the known facts? Franzen says Yes. The mainstream climate movement says No, there is still time to save things. These are not just disputed facts but lead to very different policies. We could go with the Green New Deal and spend massive resources on changing the economy; or we could—as Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang says—“move to higher ground.” Franzen and Yang argue that we should put our resources into adaptation, not pointless prevention that we know will not work (and will leave us bankrupt and therefore unable to take the needed actions).

There seem to be four popular positions on climate change: denialist, lukewarmest, crisis averter, and climate adapter.

- Denialist: Climate change perceptions are motivated reasoning, grounded in the desire by liberals to see capitalism as destructive, America as blameworthy, and more government regulation of the economy as needed. Denialists suspect that the public data on climate change are exaggerated by left-leaning academics.

- Lukewarmest: The scientific evidence of climate change is real, but does not necessarily mean that climate change is the greatest threat we face. Lukewarmests perceive the evidence of calamity to be probabilistic or unproven, and therefore likely overstated, especially when compared to other possible threats to humanity which may require greater attention than climate change.

- Crisis averter: We have a limited window left to stop climate change, especially to stay below the 2º increase identified by the IPCC as the crisis threshold. Major changes in public attitudes and substantial resources should be devoted to the project now.

- Climate adapter: The evidence is clear that it is too late to avoid massive climate shocks and disruption. Devoting limited resources toward prevention is wasteful and we should instead adapt to the coming economic and population shifts.

Liberals and Democrats demonstrate surprising variance between view 3 and view 4. Bernie Sanders advocates passing the Green New Deal and spending $15.3 trillion over 15 years on prevention. Andrew Yang argues that this is wasteful and we should take the Adapter position. His climate policy statement online is titled: “It’s Worse Than You Think.”

The backlash against Yang’s view has been severe. The Atlantic referred to as “a hyper-conservative argument,” which is not how Yang perceives it. Franzen’s New Yorker piece received immediate criticism, including a headline describing it as “the worst piece on climate change.” John Upton (editor of Climate Central) argues on Twitter that “this Climate Doomist trope flourishes—penned, best I can tell, exclusively by older, comfy white men.” Gizmodo agrees that we should “Ban Rich White Guys From Writing Their Thoughts About Climate Change.”

Franzen believes the data are clear regardless of demographics: “All-out war on climate change made sense only as long as it was winnable. Once you accept that we’ve lost it, other kinds of action take on greater meaning.”

Should we trust him? Does he have the authority to make such a claim?

He is unquestionably a great novelist. (He famously declined to participate in Oprah’s book club, but the book did quite well regardless.) Now he has turned to non-fiction as a politics and science commentator. This raises the question of whether he is even serious, or simply making an appealing, persuasive, but still fundamentally fictional argument. (See our post on bullsh*t.)

What do we make of fact claims by fiction writers? The core of the current post-fact debate is the question of expertise and trust. On all of the things outside of our personal knowledge—including climate change—which source do we trust to tell us the truth?

To put it more bluntly, when a fiction-writer turned purveyor of facts provides his assessment, and a group of scientists or a group of policy scholars disagrees, whom do you trust? Maybe it is the scientists or policy wonks. But maybe there is something to the idea that fiction is the lie that tells the greater truth (as they say). Or that any well-educated person can put together the reality with a bit of focused research. Franzen claims he is the real truth-teller because he is unconstrained and does not have to speak in couched terms or please a professional association. In other words, he doesn’t have to lie.

When asked by the Sierra Club whether his public position on climate change was irresponsible, he responded, “Well, I’m a writer, not a lobbyist, and the writer’s first responsibility is to tell the truth. So maybe the question here is, ‘Shouldn’t you just keep the truth to yourself?’ I can understand why someone trying to build a movement might think I should… The one thing I think is clearly wrong is to mislead the public about the facts.”

Franzen addresses his own epistemology and process in the New Yorker essay, which is rare and remarkable in itself:

“As a non-scientist, I do my own kind of modeling. I run various future scenarios through my brain, apply the constraints of human psychology and political reality, take note of the relentless rise in global energy consumption (thus far, the carbon savings provided by renewable energy have been more than offset by consumer demand), and count the scenarios in which collective action averts catastrophe.” If accurate conclusions depend on understanding human psychology and political reality, who better than an astute novelist, whom Nabokov described as the “conscientious observer”? In that sense, Franzen may be better than many scientists, who have little grasp of psychology or politics. He concludes, “I can run ten thousand scenarios through my model, and in not one of them do I see the two-degree target being met… So I wonder what would happen if instead of denying reality, we told ourselves the truth.”

An important critique of climate science has always been that it is often divorced from political reality. In the second Democratic debate this year, Yang mentioned the undisputed point that the U.S. accounts for only 15% of greenhouse emissions, while China and India are dramatically increasing their pollution in the drive to build their economies. For this reason alone, is it undisputed that any meaningful change in environmental policy must include agreement from those nations? Franzen and Yang’s conclusion is that this is excessively unlikely. Hence regardless of what the U.S. does the climate will deteriorate quickly. That is a deeply unwelcome conscientious observation, and hence easily dismissed and ignored.

The complexity of climate perceptions—deciding among lukewarmests, crisis averters, and climate adapters—reflects the need for broad-ranging expertise. Assuming we accept the data as legitimate (ruling out the denialist position), we are still left with assessing what the experts say about the future probabilities for the climate. We must simultaneously assess the probabilities of alternative threats that would require competing investments of resources. Are humans 50 years from now more likely to die from climate change or from the emergence of super viruses that are untreatable? The same applies to nuclear detonations or war with China and North Korea. Which of these is likely to cause more death, illness, and disruption of our way of life, and hence deserves the larger investment of resources? I don’t know anyone I would rate as truly qualified to assess these different threats independently and compare them meaningfully.

Faced with this kind of complexity, we default to our preferred narrative. Those who distrust academics and scientists tend toward the denialist position. For those who accept the public science, gravitating toward option 2, 3, or 4 is a matter of which one accords with our values and reinforces our social connections.

I admit to being unqualified to determine with confidence if the evidence truly indicates a second-tier catastrophe, avertable catastrophe, or inevitable catastrophe. But I can perceive the suggestions my values and identity are making.