Eating Disorders

CBT for Eating Disorders: A Not-Yet-Success Story

The evidence for CBT for eating disorders is weaker than you might have thought.

Posted May 4, 2018

Eating disorder treatment: The status quo

It often seems that with anorexia, still no one has a clue. You can tube feed one person back from the brink and it will kickstart real recovery, but do the same for another and induce a whole lot of physical discomfort and profound resentment, so that on discharge weight loss is the inevitable next step. One person might have years’ worth of talking therapy which eventually leads to a breakthrough that makes sense of things cogently enough to prompt behavioural change and resulting wider improvements, while for another the accumulation of insight upon insight does nothing to break the paralysis that congeals around eating, indeed it only strengthens it. Pretty much the same holds true for all the other eating disorders, though recovery rates are even lower and mortality rates higher for anorexia than the rest.

I’ve recently discovered an eating-disorder treatment that has been around for 20 years and is achieving 75% remission rates (for anorexia and other eating disorders), but which weirdly no one seems ever to talk about. The sequel to this post will explain why we need to talk about it: what it’s doing differently, what we don’t yet understand about it, what this might mean for the future of eating disorder treatment. But first, we need to understand the status quo. This involves delving into some of the murkier depths of how trials of eating-disorder treatments are currently conducted and reported. Bear with me through the numbers and the definitions. This is important. A very real devil resides in these details.

Problems with the theory: Mind-body separation

Let’s start with the theory underlying eating-disorder treatment. A large part of the failure to make more headway with is attributable, I think, to blinkered thinking about mind and body. Eating disorders tend to get classified as ‘mental illnesses’, but as I’ve often pointed out (for example here), they’re a beautiful example of the inadequacy of hard-and-fast demarcations between mental and physical: the eating or not-eating and its physical effects are just as crucial to the illness as the psychological disturbances, and inseparable from them. But the history of anorexia treatment (and to a lesser extent treatment of the other eating disorders) is a history of oscillations between extremes: focus on the physical at the expense of the psychological (refeeding and/or drug treatment with minimal psychotherapeutic support) or on the psychological at the expense of the physical (psychiatric talking therapies encouraging no change in behaviour).

CBT tries to put mind and body together again

The clinical method which has most explicitly tried to bridge this mind-body gap is cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). The bridging is there in the name: both cognition (what the mind does) and behaviour (what the body does) are put centre-stage. That behaviour, not the body, is the non-cognitive pole here is rather telling. Most significant changes made to the body happen via changes in behaviour: in anorexia, most importantly by eating more; in bulimia by stopping bingeing and purging; etc. Emphasising behavioural causes not their bodily effects helps ensure that personal agency is kept central: when bodily changes happen in anorexia treatment without an initiating personal behavioural change, as with tube feeding (sometimes against the patient’s will), it may well be that the prospects for lasting positive change of any kind are reduced. So CBT focuses on what you can change directly, and gives you tools for doing so.

As I’ve described in my post on how and why to start recovery, and explored in more depth in a book chapter on feedback loops in reading and disordered eating, the CBT model for eating disorders understands thought patterns, emotions, moods, behaviours, and physical states as inseparable, and it understands any therapeutic intervention as targeting the whole interconnected system. At any given phase in treatment, and at any given moment in a treatment session, patient and therapist may be making inroads into that system more from the behavioural direction or more from the cognitive direction: getting you to move your breakfast time forwards by an hour, say, or to interrogate what contributes to your ‘feeling fat’ right now. Each will have effects on the other, and on everything else that forms part of the mind-body feedback loop that is you – and your illness.

Now, this is the theory of CBT, and the practice may reflect it with varying emphases and blindspots. Some practitioners may neglect the weight-restoration aspect, some may allow it to overshadow everything else, and some may find an appropriate balance which changes as recovery progresses. In my own experience of ‘enhanced’, or personalised, transdiagnostic CBT for eating disorders (CBT-E) with Chris Fairburn’s team at Oxford, the initial aim was the simple behavioural one of eating more (specifically 500 kcal a day more), in whatever way felt most manageable. The dubious nutritional balance of my diet, the long fast before the single meal late at night, the secretive seclusion of it all – these things could wait. The theory was that they would resolve of their own accord, or be more effectively addressed, once the basic malnutrition had been improved a little. And that seemed to be what happened: experimenting with more varied foods, starting to eat with other people again, starting to eat earlier in the day, all happened with differing degrees of speed, ease, and targeted encouragement in the weeks and months that followed.

Arguably, however, I took the hardest step alone, by changing my own behaviours: by regaining without support the 2 kg I needed to be admitted on to the programme. Once someone with anorexia has enough conviction in their own desire not to be ill any longer to start eating significantly more without help, they will probably make significant improvements regardless of subsequent support. Nonetheless, I got fully better where so many others do not, and I don’t want to downplay the significance of any part of what helped that happen. (And, this being real life with a sample size of 1, I can never do the controlled experiment that would allow me to know what would have happened with any single part removed.)

Researching this post, I’ve discovered a lot about CBT that has been surprising and disappointing to me. But as you read on, please don’t take my criticisms of how CBT is currently practised and reported as reasons not to seize the opportunity to have CBT treatment if you have an eating disorder and CBT is available to you. The point of this post is to explain what could be done better in treatment and research, and to motivate the sequel, about an important alternative to CBT. Remember that statistics say nothing about the individual, and that your experience of CBT may be, as mine was, an utterly positive contributor to full recovery. Anorexia is always looking for ways to survive, and it’s a pretty sure bet that it will survive better with no treatment than with treatment. And the fact that mind-body interactions are taken seriously in a CBT framework makes it a better bet than paradigms where these interactions are neglected.

CBT efficacy for bulimia is relatively weak – and its presentation sometimes misleading

On paper, then, it seems that some version of CBT should be the way forward: a method that at last overcomes the dualism of mind versus body and puts the two back together again. But the empirical results are not nearly as glowing as we might expect. Recent trials for bulimia report remission rates of about 45% and a one-year relapse rate of around 30% (Södersten et al., 2017). These are Södersten and colleagues’ estimates based on a comprehensive review of every paper on CBT for eating disorders since Fairburn’s 1981 report. This remission rate is more generous than Hay et al.’s (2009) 37% and in line with Lampard and Sharbanee’s (2014) range from 30%-50%. If a 45% remission rate doesn’t seem too bad, bear in mind that 1) this is remission we’re talking about, not recovery; and 2) if in 30% of cases remission has already given way to relapse within a year, it’s debatable whether it should ever have been called remission. As I’ll show, the standard definitions of remission and recovery would be laughable if they weren’t so angering. And the relapse statistics are not only worryingly high, but partially concealed by worrying methods.

First off, it’s worth saying that there’s something of a monopoly at work in CBT trials for eating disorders. Chris Fairburn is involved in virtually all studies, and independent replications are rare. The first attempt at one was by Katherine Halmi and colleagues in 2002. She reported a 44% rate of relapse within four months after CBT ended, leaving only 14% of 194 patients in remission at that time. For the supposedly pre-eminent treatment for bulimia, this is a pretty damning finding. In response, Fairburn and Cooper explained in a 2003 letter to the Archives of General Psychiatry (the journal which published Halmi’s paper) that in their studies the rate of relapse is ‘matched by an equivalent rate of remission among those participants who were not yet fully asymptomatic at the end of treatment’. That is, the headline remission rates are achieved by replacing those who relapse with the same number who do remit after the end of treatment. It is deeply bizarre to me that they present this as a positive in the attempt to counter Halmi’s results. What’s actually going on here?

The study Fairburn and Cooper quote in the 2003 letter to back up this point about relapse-remission ‘matching’ is Stuart Agras and colleagues’ ‘Multicenter comparison of cognitive behavioural therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy for eating disorders’ (2000). The same strategy is employed in more recent studies on bulimia too, like Stig Poulsen and colleagues’ ‘Randomized controlled trial for psychoanalytic psychotherapy versus cognitive-behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa’ (2014). (Fairburn is an author on both papers.) So let’s look at these two in a bit more detail.

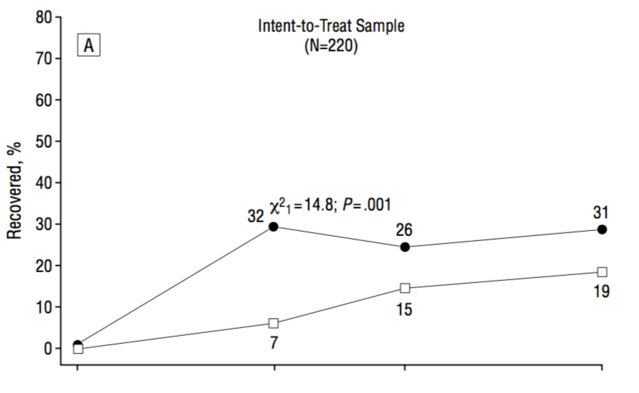

Agras et al. report that at the end of follow-up (i.e. after 12 months), 21 (66%) of the 32 people who had recovered after being treated with CBT (29% of the total) ‘remained recovered’. That is, 11 (34%) had relapsed. Meanwhile, 6 (or 29%) of the 21 people who had gone into ‘remission’ after CBT, and 4 of those who had not, were classified as ‘recovered’ at the end of follow-up. 21 + 6 + 4 = 31, just one fewer than the original ‘recovered’ total. This result is presented in the following line graph, which gives the strong impression that the 32 and the 31 refer to the same people.

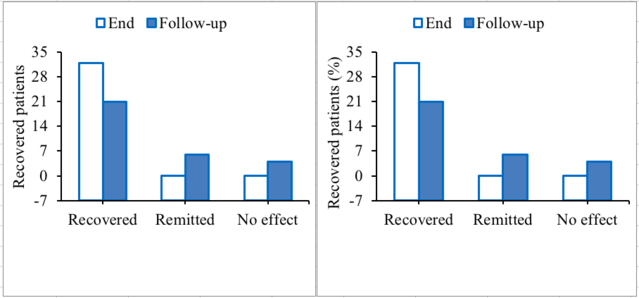

A more transparent way to present the data would be to use bar charts, which don’t mislead us into thinking that each category contains the same participants.

Instead, quite a few of the people who ‘recover’ relapse; quite a few who were in ‘remission’ ‘recovered’; and some of those who were still ill ‘recovered’. This gives me a strong sense that none of these results means anything much. Presumably, if so many of the ‘recovered’ people relapsed within a year, it’s likely that a large proportion of those who ‘recovered’ at follow-up (after having either remitted or not at end of treatment) relapsed too, but whether these people were followed up on at all is not reported. If it had been, would we simply have seen more relapse masked by more replacements? Where does the cycle of instability end?

Sticking with bulimia for now, the same pattern repeats itself in Poulsen et al. (2014): here too, the presentation of the results makes it almost impossible to track any individual patient’s progress. The line graph presents a neat story which looks like universal maintenance of recovery status at follow-up, but which when you dig into the details turns out to look entirely different, and to echo Agras et al.’s results. Here, 42% (15) patients treated with CBT (of whom only 28 completed the treatment) were in remission at end of treatment, and 44% (16) were still in remission after another 19 months, but these weren’t the same 15. Only 10 (66%) of those who had been in remission remained so, i.e. 5 (34%) relapsed; while 6 (29%) of those who were still bingeing and purging at end of treatment had remitted by follow-up. It’s also worth noting that 11 (39%) of those who completed the CBT had additional treatment (of undefined kinds) during the follow-up period.

Interestingly, this pretty but misleading line graph was reproduced in the editorial of the journal issue where Poulsen and colleagues’ paper was published (Hollon and Wilson, 2014), and is singled out for special praise in what they call a ‘remarkable’ paper:

If every figure tells a story, the story told by the left panel of the second figure in the published article (the number of participants who no longer binged or purged) is the most dramatic that we have seen in the literature […] [It is] important to highlight the potency of enhanced CBT and the impressive maintenance of change over the 19-month follow-up. (p. 13)

This figure certainly does tell a story, but sadly not the one the editors would like it to. They make special mention of the authors’ honesty in reporting the unexpected superiority of CBT over psychoanalytic psychotherapy, saying: ‘we applaud the candor of the lead investigators for being so forthright in their presentation of the findings’ (p. 15). The ironies are multi-layered.

The distinction between remission and recovery is blurry, and both terms are exaggerations.

The obvious conclusion from all this is that the criteria for ‘remission’ and ‘recovery’ being applied here are so inadequate that achieving either of them is not a reliable predictor of genuine and lasting recovery. Agras et al. define remission as binge eating and purging less than twice a week for 28 days, and recovery as not bingeing or purging at all for 28 days. Poulsen et al. talk about ‘cessation of binge eating and purging’, and also use the 28-day criterion. There’s an odd asymmetry here, given that the DSM-V definition of bulimia requires bingeing and purging to have continued for three months, not just one. Why would we make the definition of recovery so much more lax than that of illness – unless we were trying to demonstrate the efficacy of a treatment we had vested interests in validating?

These definitions – the one for remission as much as the one for recovery – make me wonder: how much of the point of all this is to make sure one gets results that can be massaged into looking like publishable successes? Declaring someone recovered who hasn’t binge-eaten or made themselves vomit for the last 28 days is like celebrating their escape from a sinking ship without troubling to note, from the comfort of your helicopter, that they’re stuck in shark-infested water miles from land and their lifeboat may have a hole in it.

A ‘recovery’ rate of 29% followed by 34% relapse (as reported by Agras et al.) is the opposite of impressive. Likewise (another way of parsing their results) the fact that the frequency of bingeing over the last four weeks of the follow-up period increased in 34% of patients and decreased in 19% of patients). (The calculations for the increase: 11 [relapsed after ‘recovery’] + 7 [remitted after treatment then relapsed] = 18/53 = 34%. And for the decrease: 4 [not remitted at end of treatment, but ‘recovered’ at follow-up] + [remitted at end of treatment and recovered by follow-up] = 10/54 = 19%.) Overall, Södersten and colleagues’ (2017) conclusion that ‘reports on remission, relapse, and long-term effects of CBT are inconclusive’ (p. 178) starts to look like the definition of diplomacy.

As we saw, in Halmi et al.’s 2002 study, which employed no such masking techniques, the results are drastically less positive. But in their response to Fairburn (2003), you can feel them backtracking awkwardly to try to make his results sound better than they were. They claims that their definition of ‘abstinence’ from bingeing and purging for 28 days is ‘highly sensitive’, and insist that most of their patients were ‘actually doing very well’ even if they didn’t meet this criterion, with ‘only’ 25% ‘clinically impaired’. The letter concludes that ‘these findings definitely support rather than undermine the standing of CBT as a potent treatment for bulimia nervosa.’ This obfuscating, obsequious language is in stark contrast to the blunt conclusion stated in the abstract to the original paper: ‘Four months after treatment, 44% of the patients had relapsed. […] The effectiveness of early additional treatment interventions needs to be determined with well-designed studies of large samples.’

CBT for anorexia is disappointing too.

So, CBT for bulimia does work for some people, but for many others it doesn’t – or isn’t given a chance to, because treatment is brought to a premature end by barely defensible definitions of success. By no means all studies employ the dubious relapse-concealment methods, but the fact that any do makes us wonder what other questionable tactics might have been employed in the research or its reporting in this field. And then of course, even these seriously massaged graphs don’t exactly look impressive. So what about anorexia? It’s still much earlier days when it comes to using CBT (or the ‘enhanced’ version, CBT-E) to treat anorexia, and results so far are distinctly mixed, with patients typically gaining weight but not to normal levels, and with relatively high drop-out rates (up to 37%) and significant trends towards relapse during (patchy, fairly short-term) follow-up (Dalle Grave et al., 2013; Fairburn et al., 2013; Touyz et al., 2013; Calugi et al., 2015; Calugi et al., 2017). (Dalle Grave et al., 2014 achieve better results; I return to this observation in the sequel to this post.) (In case you’re wondering, another currently popular treatment, family-based therapy, has shown some promise for adolescents with short prior illness (Le Grange et al., 2008), but there is no consistent evidence that it is more effective than other treatments, and relapse or additional treatment is often observed in the follow-up period (Lock et al., 2010; Le Grange et al., 2014).)

Hardly any follow-ups are conducted beyond a year or two, and when they do happen, the findings can be questionable. For example, a 2017 review (Södersten et al., 2017, p. 182) observed that ‘In a long-term follow up study [Carter et al., 2011], 12 of 19 patients with a relatively high average BMI = 17.3, completed CBT. The patients were reported to have normal BMIs on average 6.7 years later (=20.2) but since this outcome included five patients who did not complete the treatment, the results are difficult to interpret.’ This echoes the problems we explored in the bulimia trials: significant instability between treatment and follow-up, with discrepancies left unexplained.

Overall, evidence is incomplete and inconsistent, and with ‘recovery’ rates around 30%, ‘CBT’s outcomes for anorexia nervosa remain disappointing. However, that disappointment needs to be understood in the context of the even poorer outcomes of other therapies for anorexia nervosa’ (Waller, 2016). Glenn Waller notes that other treatments see only around 30% of patients achieving remission at end of treatment. And remission itself is, as ever, generally defined with disappointing laxity (see my discussion of the problem of drastically low BMI criteria for ‘recovery’ here).

Inconsistency is a serious issue here too: a recent review of what happens after treatment of anorexia (Khalsa et al., 2017, p. 6) concluded that ‘The main finding of this review is that there are almost as many definitions of relapse, remission, and recovery as there are studies of them’. Given that researchers generally manage to agree on definitions of the disorders themselves, one would expect agreement on its resolution or return to be possible too – and if such agreement remains absent, it’s easy to suspect ulterior motives. Khalsa and colleagues make sensible suggestions for definitions and follow-up protocols to adhere to, and it’ll be interesting to see whether or not they’re adopted.

Finally, as for the precise paths to change, it’s not at all clear that the results achieved through CBT or CBT-E are indeed the results of the hypothesised mechanisms; particularly for CBT-E, there’s evidence that the treatment modules meant to help with self-esteem and interpersonal problems respectively may not in fact be driving the improvements observed on these dimensions (Lampard and Sharbanee, 2015).

This is all pretty dispiriting. I find it a little disorientating, given how positive my own experience of CBT-E was, to understand just how little research there is on CBT for anorexia, and how far from reliably positive the results are from the research that has been done. Of course, running long-term experimental interventions is a tricky business, and human beings with illnesses will not always get better. But when we do research involving other human beings, we need to take extra care, in both the conduct and the publication of the research we do.

The story doesn’t end unhappily here, though. The next instalment has taken me from an autumnal visit to the University of California to a Stockholm clinic in the last of the spring snows. It gives us a breath of greater hope, some interesting questions to ask, and some urgent next steps to call for. You can read it here.

References

Agras, W.S., Walsh, B.T., Fairburn, C.G., Wilson, G.T., and Kraemer, H.C. (2000). A multicenter comparison of cognitive-behavioral therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy for bulimia nervosa. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57(5), 459-466. Open-access full text here.

Calugi, S., Dalle Grave, R., Sartirana, M., and Fairburn, C.G. (2015). Time to restore body weight in adults and adolescents receiving cognitive behaviour therapy for anorexia nervosa. Journal of Eating Disorders, 3(1), 21. Open-access full text here.

Calugi, S., El Ghoch, M., and Dalle Grave, R. (2017). Intensive enhanced cognitive behavioural therapy for severe and enduring anorexia nervosa: A longitudinal outcome study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 89, 41-48. Paywall-protected journal record here.

Carter, F.A., Jordan, J., McIntosh, V.V., Luty, S.E., McKenzie, J.M., Frampton, C., ... and Joyce, P.R. (2011). The long‐term efficacy of three psychotherapies for anorexia nervosa: A randomized, controlled trial. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 44(7), 647-654. Direct PDF download (final version) here.

Dalle Grave, R., Calugi, S., Conti, M., Doll, H., and Fairburn, C.G. (2013). Inpatient cognitive behaviour therapy for anorexia nervosa: A randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 82(6), 390-398. Open-access full text here.

Dalle Grave, R., Calugi, S., El Ghoch, M., Conti, M., and Fairburn, C.G. (2014). Inpatient cognitive behavior therapy for adolescents with anorexia nervosa: Immediate and longer-term effects. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 5, 14. Open-access full text here.

Fairburn, C. (1981). A cognitive behavioural approach to the management of bulimia. Psychological Medicine, 11, 707. Paywall-protected journal record here.

Fairburn, C.G., and Cooper, Z. (2003). Relapse in bulimia nervosa. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60(8), 850. Paywall-protected journal record here.

Fairburn, C.G., Cooper, Z., Doll, H.A., O'Connor, M.E., Palmer, R.L., and Dalle Grave, R. (2013). Enhanced cognitive behaviour therapy for adults with anorexia nervosa: A UK–Italy study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 51(1), R2-R8. Open-access full text here.

Halmi, K., Agras, S., Mitchell, J., Wilson, T., and Crow, S. (2003). Relapse in Bulimia Nervosa—Reply. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60(8), 850-851. Paywall-protected journal record here.

Halmi, K.A., Agras, W.S., Mitchell, J., Wilson, G.T., Crow, S., Bryson, S.W., and Kraemer, H. (2002). Relapse predictors of patients with bulimia nervosa who achieved abstinence through cognitive behavioral therapy. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59(12), 1105-1109. Open-access full text here.

Hay, P.J., Bacaltchuk, J., Stefano, S., and Kashyap, P. (2009). Psychological treatments for bulimia nervosa and bingeing. Cochrane Database Systematic Review, 4, CD000562. Paywall-protected journal record here.

Hollon, S.D., and Wilson, G.T. (2014). Psychoanalysis or cognitive-behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa: The specificity of psychological treatments. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(1), 13-16. Open-access full text here.

Khalsa, S.S., Portnoff, L.C., McCurdy-McKinnon, D., and Feusner, J.D. (2017). What happens after treatment? A systematic review of relapse, remission, and recovery in anorexia nervosa. Journal of Eating Disorders, 5(1), 20. Open-access full text here.

Lampard, A.M., and Sharbanee, J.M. (2015). The cognitive‐behavioural theory and treatment of bulimia nervosa: An examination of treatment mechanisms and future directions. Australian Psychologist, 50(1), 6-13. Paywall-protected journal record here. Direct PDF download (preprint) here.

Le Grange, D., Accurso, E.C., Lock, J., Agras, S., and Bryson, S.W. (2014). Early weight gain predicts outcome in two treatments for adolescent anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47(2), 124-129. Open-access full text here.

Le Grange, D., and Eisler, I. (2009). Family interventions in adolescent anorexia nervosa. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics, 18(1), 159-173. Paywall-protected journal record here.

Lock, J., Le Grange, D., Agras, W.S., Moye, A., Bryson, S.W., and Jo, B. (2010). Randomized clinical trial comparing family-based treatment with adolescent-focused individual therapy for adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67(10), 1025-1032. Open-access full text here.

Poulsen, S., Lunn, S., Daniel, S. I., Folke, S., Mathiesen, B.B., Katznelson, H., and Fairburn, C.G. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of psychoanalytic psychotherapy or cognitive-behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(1), 109-116. Open-access full text here.

Södersten, P., Bergh, C., Leon, M., Brodin, U., and Zandian, M. (2017). Cognitive behavior therapy for eating disorders versus normalization of eating behavior. Physiology & Behavior, 174, 178-190. Full-text PDF here.

Troscianko, E.T. (2016). Feedback in reading and disordered eating. In M. Burke and E.T. Troscianko (Eds), Cognitive literary science: Dialogues between literature and cognition (pp. 169-194). New York: Oxford University Press. Abstract here. Google Books preview here.

Touyz, S., Le Grange, D., Lacey, H., Hay, P., Smith, R., Maguire, S., ... and Crosby, R.D. (2013). Treating severe and enduring anorexia nervosa: A randomized controlled trial. Psychological Medicine, 43(12), 2501-2511. Paywall-protected journal record here.

Waller, G. (2016). Recent advances in psychological therapies for eating disorders. F1000Research, 5. Open-access full text here.