Neuroscience

The Neuroaesthetics of Handaxes

Were handaxes the first forms of art?

Posted May 12, 2015

Co-author Anne A. Kelly

In an earlier post, we introduced the ancient stone tool design known as a handaxe and discussed some of the implications that it has for the evolution of cognition. Here we continue this discussion from a slightly different perspective, that of aesthetic expression.

It is still typical for art history courses to begin with a cursory discussion of the famous European Upper Palaeolithic painted caves (about 45,000 – 12,000 years old). And one often hears two claims about this art: first, it represents the first expression of the human imagination, and second that there are no known antecedents. These beautiful painted animals and geometric patterns are supposed to have suddenly appeared in a kind of explosion of human creativity. This is a romantic story, and it is almost certainly wrong. Evolution just doesn’t work this way.

How have art historians managed to miss seeing the antecedents? We suggest that there are two primary reasons for this ignorance. First, scholars think the antecedents must have consisted of cruder pictorial art, i.e., that it was depictive in the same way as the cave paintings, just not as good. Second, art historians may be using inappropriate theories.

We believe a better approach is to look not for depictive art objects, but for developments in tools, and use an explicit cognitive model in our search. The model we choose is the relatively recent perspective in cognitive neuroscience known as neuroaesthetics. Since 1999 cognitive neuroscientists such as Semir Zeki, V. S. Ramachandran, Anjan Chatterjee, and Helmut Leder have made a concerted study of the neural resources used in aesthetic experience, providing a powerful theoretical context for studying prehistoric artifacts.

The first conclusion to be drawn from neuroaesthetics is perhaps the most important: there is no part of the human brain dedicated to aesthetic experience. Instead, the brain uses circuitry that evolved for other purposes, but in a new way. Of course, specialists in neuroaesthetics do not agree on everything, but there does appear to be general agreement that at least three relatively distinct neural circuits participate in visual aesthetic experience (we will save other domains, such as music, for another time). These are the visual processing circuits, emotional processing circuits (especially pleasure/reward), and cultural knowledge/meaning circuits.

Here we will focus on the first two, because it is our contention that handaxes required the contribution of both.

Ramachandran and Hirstein have suggested that all artistic experience can be characterized by ten universals. Three of these principles are features of visual processing that can be recognized in Acheulean handaxes: Symmetry, Peak Shift Principle, and Perceptual Ambiguity. Attraction to symmetry is hardwired in humans (and other mammals). We like symmetry in faces, interior design, and the beautiful symmetry of the ‘overdetermined’ handaxes.

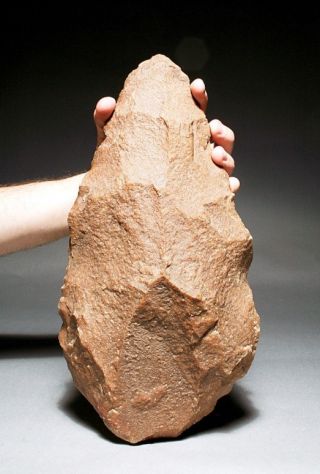

Handaxe from Kathu Pan, South Africa (ca. 500,000)

Peak Shift, at its simplest, states that if X is good 2X is better. Giant and miniature handaxes demonstrate Peak shift – less is more and, sometimes, more is more.

Perceptual ambiguity (think Salvador Dali) is harder to recognize in Paleolithic artifacts, but it is there. It refers to a visual uncertainty or mystery. The makers of handaxes often included ambiguous shapes within the outline of a handaxe or, in this case, a feline face in a cleaver:

What these handaxes and many others demonstrate is that by half-a-million years ago hominids were exploiting features of visual processing that are important in artistic productions today. Clearly this component is much older than 45,000 years!

The pleasure/reward circuitry was also employed in handaxes. As it turns out, beautiful examples such as the Kathu Pan handaxe above are actually fairly rare. There are literally thousands of handaxes from the site of Kathu Pan, but almost all are drab affairs that are vaguely symmetrical but not highly finished. It is as if the knapper of this tool recognized a beautiful piece of iron stone and devoted extra effort to produce a lovely outcome. It clearly gave him or her pleasure to do so. This pattern of many average artifacts and a few brilliant exceptions is actually the norm for handaxe collections. There are some exceptions, where almost everything is highly finished, but this is very unusual (the best example being Boxgrove, a 500,000-year-old site in Britain). The handaxe makers were clearly making judgments about pleasing forms, and this judgment/appraisal component is also very important in modern aesthetic productions.

Thus, the archaeological evidence clearly documents important antecedents to modern aesthetic production as early as half-a-million years ago. What we haven’t discussed is the third component of modern artistic production – cultural meaning. We’ll save that for another post.