Fear

Reduced Cancer Screening During COVID: Cause for Alarm?

Most cancer screening has only moderate benefit, but can also cause great harm.

Posted March 9, 2021 Reviewed by Devon Frye

You've probably seen the widespread warnings that the temporary decline in screening for breast, colorectal, and cervical cancer (the rates dropped sharply last spring but have returned to nearly normal) will lead to lost lives. But those warnings, which resonate with our almost religious belief in the benefits of cancer screening, miss a critical part of the story. The life-saving benefits of most cancer screenings are moderate, while the harm that screening can cause is enormous and in many cases severe, including loss of life itself.

Our blind belief in screening is based on the universally assumed truth that finding cancer as early as possible is always best. Modern cancer screening itself has taught us that this is not always true. Ever-more perceptive new technologies that can now find some cancers much earlier, when they are much smaller, have led to sharp increases in the incidence of breast, prostate, and thyroid cancer. Yet the mortality rate for those diseases has not declined by nearly as much, or at all. Finding all those extra cancers earlier is not saving more lives. Why?

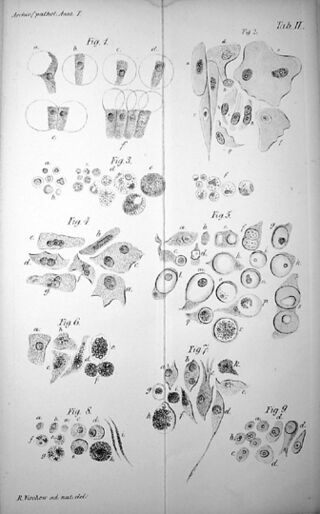

Because not all cancers behave the same. While cells may meet the visual criteria of cancer under the microscope (criteria established by Dr. Robert Virchow in the 1850s, whose drawings still form the basis of how pathologists diagnose cancer today), some of the early forms of cancer screening can find never develop the ability to metastasize and spread through the body, which is how most cancers kill. And some never grow, or grow so slowly that they never cause any symptoms in the remaining lifetime of the patient. (Roughly 50 percent of cancers are diagnosed in people over 65.)

Examples of such cancers include:

- Roughly one case in five of breast cancer is Ductal Carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Most of these cancers, if left completely alone, will never cause any harm in the lifetime of the patient.

- As many as half of all prostate cancers, if left untreated, would never cause harm in the patient’s lifetime.

- Between 80 and 90 percent of thyroid cancers are a type called papillary, the long-term survival rate for which is 99 percent with treatment and 97 percent with none.

But because cancer is so feared—two people in three, when asked, “What’s the first thing that comes to mind when you hear the word ‘cancer’?” reply “death"—most people diagnosed with cancer choose to have it surgically removed… even when they are told that their cancer is a type that will almost certainly never cause them any harm and can be treated with nothing more than ongoing monitoring and surgical intervention later, if the cancer becomes more threatening. Afraid of cancer, tens of thousands of people choose to remove their breasts or prostate glands or thyroid glands or parts of their lungs, risky procedures their clinical conditions may not require. Their medical condition scares them more than it threatens them. Essentially, these operations are "fear-ectomies."

Consider just two examples of the harm this can lead to:

- Across the 40 years of mammography in the U.S. (1977-2017), during which there were roughly 18 million mammograms per year, it has saved roughly 144,000 lives. (Two lives saved per 1,000 people screened over a ten-year period.) Over that period, surgery for low grade/low-risk DCIS (lumpectomy, unilateral or bilateral mastectomy) killed roughly 800 women, left roughly 250,000 with Post Mastectomy Pain Syndrome (long term pain in the chest/arm), and caused hundreds of thousands of women psychosocial harm connected with body image issues. And that doesn’t consider the psychological/emotional harm from nearly 5 million false positives per year, women who hear the frightening news after a mammogram “We found something suspicious…"—i.e. “You may have breast cancer”—but who ultimately learn they don’t.

- From 1992, when PSA testing for prostate cancer exploded onto the market, through 2017, it saved the lives of an estimated 9,800 men. But 165 million men were told their test indicated the possibility of prostate cancer, had biopsies to make sure, and found out they didn’t have it after all. 1.65 million had to be hospitalized after their biopsies caused infection or bleeding. 560,000 men went on to have surgery for a type of cancer that would almost certainly never have harmed them, and that surgery killed 2,800 men, caused erectile dysfunction in 373,000, the loss of urinary control in 113,000, and the loss of bowel control in 85,000.

(These calculations have been reviewed by Dr. Anthony B. Miller of the University of Toronto.)

The economic costs of what is called “overdiagnosis” and “overtreatment” are equally as staggering. As are the costs of the “overscreening” that initiates these medical cascades... the millions of people a year who, worried about cancer, opt for screening though they have none of the risk factors—age, genetics, etc.—warranting such tests.

The CDC reports that in 2015, 20.2 million women younger or older than the ages recommended for mammography screened anyway. 4.8 million men outside the age ranges recommended for PSA testing had a test anyway. 17.2 million people outside the recommended age range screened for colorectal cancer. (Recommendations are based on who screening is more likely to benefit than harm. You can find the recommended age ranges here.)

- The annual cost of overscreening and overtreatment of low-grade/low-risk DCIS cancer is, very roughly, $1.9 billion for Medicare and $6.9 billion for private insurance, a total for the U.S. health care system of $8.8 billion dollars.

- The annual cost of overscreening and overtreatment for low-grade/low-risk prostate cancer is $636 million for Medicare, $1.1 billion for private insurance, a total of $1.7 billion.

- Including treatment of low-grade/low-risk “overdiagnosed” lung, thyroid, and other types of cancer (colorectal, melanoma), roughly 6 percent of all money spent on cancer care per year—$207 billion—is spent on care to treat a frightening disease… care that is likely clinically unnecessary.

- Lost productivity from this overtreatment adds an additional cost to the economy of roughly $7.9 billion per year.

(These calculations have been peer-reviewed by three researchers at the U.S. Agency for Health Quality Research.)

Our sometimes excessive fear of cancer, what some have coined "cancerphobia," causes significant harm in other ways as well.

- Millions who are at risk and should screen, don’t, afraid to learn they have cancer. For the same reason, hundreds of thousands of people with early symptoms delay going to the doctor. Many of these people suffer worse outcomes.

- Society spends tens of billions of dollars on products that claim to reduce the risk of cancer (organic food, natural supplements, all manner of quack products and devices), but don’t.

- Many people oppose technologies that offer society great benefit—cell phone towers, greenhouse gas-free nuclear energy—because they are associated with cancer, though the risk is actually tiny (nuclear power) or non-existent (cell phone tower radiation).

We’ve made great progress treating those cancers that do threaten our lives—as many as two-thirds of all cancers can now be treated as chronic disease or cured outright—and identifying those that don’t. We have also learned that our fear of this dreaded disease sometimes exceeds the risk, and the fear can also lead to great harm. Now, it’s time to apply what we’ve learned to update our emotional relationship with The Emperor of All Maladies, because while we've come a long way toward the goal of curing cancer, we've really only just begun the work of curing our cancerphobia.